Meet the farmer and visionary who founded Fresh Future Farm, a nonprofit farm and grocery store, to serve a food desert in North Charleston’s Chicora-Cherokee neighborhood

Farmer and community visionary Germaine Jenkins revels in a harvest of healthy greens from her North Charleston nonprofit, Fresh Future Farm.

In the formerly vacant lot beside the old Chicora Elementary School, Jenkins and her team have created an urban oasis, where neighbors can buy freshly harvested vegetables and fruits and learn about growing and preparing nutritious food.

In the heart of Chicora-Cherokee, a North Charleston neighborhood bisected by railroad tracks and pocked with abandoned buildings, Success Street intersects Spruill Avenue near the old, abandoned Chicora Elementary School. “Success” is an apt roadway moniker, for just down the block, at the center of this low-income neighborhood with the lowest rate of home ownership and one of the highest rates of crime in the area, you’ll find Fresh Future Farm (FFF) and its founder, Germaine Jenkins.

On the nearly an acre that comprises this oasis, groves of lush banana trees and tall stalks of sugar cane give the disorienting sense that perhaps you’ve landed in Barbados or Costa Rica. Neat rows of dark green kale fall in line beneath the bananas, their furling leaves contrasting the lanky fronds of the fruit trees. Pears and pawpaws grow nearby, as do peppers and eggplant. Chickens scurry about. Farmer Jenkins scurries about, too, wearing her signature straw hat tied beneath her chin, pulling weeds here, trimming plants there. Tending, forever tending—and dreaming.

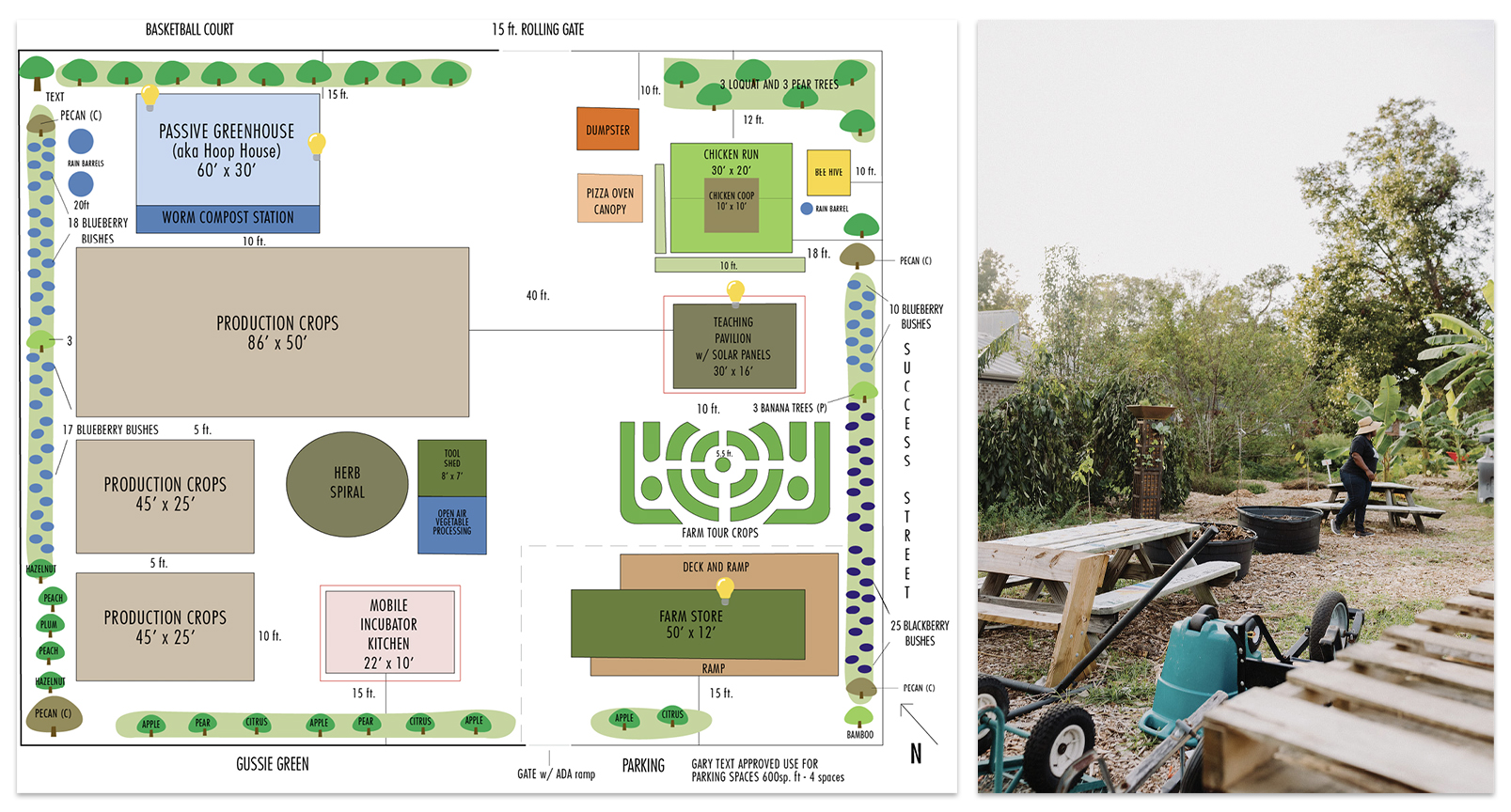

With its harvest sold in the on-site grocery store, Fresh Future Farm has already ripened into more than Jenkins imagined when she first planted the nonprofit’s seeds in 2014—and she’s got even bigger plans for its future. Thanks to a successful “Claim our Roots” Kickstarter campaign this summer, she and her board have $72,500 to begin carrying out those dreams, starting with purchasing the land the nonprofit has been leasing from the City of North Charleston. Solar panels and a mobile kitchen will be installed on the property, and a new pavilion, where Jenkins plans to hold more cooking classes and educational events, is in the works.

If you’re getting the sense that FFF is more than a farm, you’d be correct. In Jenkins’s mind, it’s a “mutual aid organization”—a catalyst for growing a healthier community through a multi-pronged strategy that “leverages quality food and jobs to create self-sufficiency.” The farm provides healthy and affordable food to neighbors in Chicora-Cherokee, where the only nearby grocery options include a recently opened Dollar General and corner mini-marts full of packaged, processed foods.

In other words, Fresh Future Farm and its neighbors exist in a food desert, an area “more than one mile from a grocery store that has limited access to other outlets, such as corner stores, farmers markets, food hubs, and mobile markets,” as defined by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). Residents of Chicora-Cherokee are far from alone in the desert. More than one million low-income South Carolinians, from the Upstate to the Lowcountry, live in them, according to a USDA report using 2014 data. And study after study shows that food insecurity disproportionately affects minority communities.

By planting these nutritious seeds and increasing access to healthy foods, Jenkins aims to impact the “health and quality of life for marginalized people,” she says. Her ultimate goal? To address the root causes that lead to food insecurity, poverty, and vulnerability. That’s a lot to ask of fruit trees and leafy greens growing on a formerly vacant lot, but not when Jenkins is tilling the soil.

In the formerly vacant lot beside the old Chicora Elementary School, Jenkins and her team have created an urban oasis, where neighbors can buy freshly harvested vegetables and fruits and learn about growing and preparing nutritious food.

Growing a Farmer

Born in Hartsville, South Carolina, and raised in Cleveland, Ohio, Jenkins never envisioned that she’d become a permaculture expert or master tree planter, much less the head of a nonprofit. But food has always been a passion, and is what initially brought her back to South Carolina in 2000, when she moved to Charleston to attend Johnson & Wales. “I wanted to be a baker,” says Jenkins. And so she went to school and worked the breakfast shift at Embassy Suites Hotel in North Charleston, while juggling childcare for her two toddlers—eldest child, Anik, and son, Adrian. “I found a day care that was open 24 hours; I was dropping the kids off at 5 a.m. and picking them up at 8 p.m.,” she says. “That didn’t last long.”

Childcare wasn’t her only challenge. Jenkins didn’t have nearby family or friends to lean on for support. “I was struggling. We had a pretty immediate need for food,” she recalls. “We qualified for SNAP benefits, but I had to stretch them by standing in pantry lines—I hated it. But one day, I realized that I could grow my own food.” She made a promise to her kids that they would move out of City of Charleston public housing and into their own home, with their own garden.

After graduating from culinary school, Jenkins began working as the Kid’s Cafe cook at Cannon Street YMCA and later as nutrition coordinator for Lowcountry Food Bank. It was there that she met Bill Stanfield, CEO of Metanoia, whose organization was an agency of the food bank. “He encouraged me to buy a house,” says Jenkins, which she did thanks to participating in Metanoia’s financial literacy workshop, or “How to Buy a House 101 program,” as Jenkins calls it.

In 2007, she and her family moved into their own North Charleston home, about five minutes from Success Street. Jenkins took classes through the Clemson Extension Master Gardener Program and began planting the garden she’d envisioned for her children. But from the beginning, her aspirations went beyond her own backyard. “The quality of the food we were growing at our house is what I wanted everyone to have access to. So that’s what we did.”

Jenkins became Metanoia’s part-time community garden manager and began nurturing and cultivating her own ideas. She participated in NeighborWorks conferences in Philadelphia, Detroit, Portland and Cincinnati—programs of NeighborWorks America, a national network that supports community development organizations. There she learned about “asset mapping,” a tool to identify resources and opportunities that might not be obvious.

“I was asset mapping in my own household, using the resources at hand because that was all I could afford. I was home-schooling Adrian for a while. He would help me in the garden, then we cooked healthy food together, and I started a blog about it,” she says. Ultimately, though, those maps were leading Jenkins toward launching Fresh Future Farm. “I wanted to address the food apartheid that I had experienced. I was hyper-focused,” Jenkins says.

Through sharing her ideas with people like Todd Chas of CharlestonGOOD, a collaborative support network for Lowcountry nonprofits and grassroots programs, along with fellow Metanoia board members, she learned about the SC Community Loan Fund’s Feeding Innovation program. She applied for, and received, funding to earn Commercial Urban Agriculture certification from Growing Power Inc., which entailed traveling to Milwaukee one weekend a month for six months in 2014. All the while she was driving her now middle and high school-aged children from North Charleston to school in West Ashley and James Island every day. “I was spending a lot of time in the car—not ideal, especially when the AC went out,” she says. “But that’s what you do when you live in a neighborhood with underperforming schools and you’re determined that your kids get a good education.

“Situational poverty is complex. I had nothing to do with the limited infrastructure in the neighborhood I moved into, or the fact that I had to drive my kids out of the neighborhood to get a quality education,” Jenkins adds. “It’s very expensive to be poor. Everything costs more.”

All Hands on Deck: The farm’s core team gets lots of help from volunteers, such as these employees from Stantec, pictured with Jenkins next to the farm store. The mural, which special projects manager Anik Hall researched, organized, and painted, depicts 500 years of the Chicora-Cherokee neighborhood’s history.

Up & Running

Through SC Community Loan Fund’s Feeding Innovation competition, Jenkins won $25,000 in seed money to launch Fresh Future Farm—only 10 percent of her proposed budget. She transformed a donated modular building, which had a deck but no entry stairs, into the farm’s grocery store. “We had to pole vault into it,” she says with a laugh. In the fall of 2014, she and a team of volunteers planted blackberries, blueberries, and fruit trees on the lot that Jenkins was leasing from the City of North Charleston. With new stairs and a fresh coat of paint, the store opened as a hub, where neighbors could buy freshly harvested organic vegetables, kombucha, and other local and health-oriented products—“and neck bones and potato chips,” adds Jenkins, “we don’t judge people based on their food choices”—using SNAP benefits or purchasing on a sliding scale.

But Jenkins’s mentors and her board were still concerned that FFF didn’t own the land. “Land ownership is central to long-term sustainability. Without that, all Germaine’s hard work and investments in improving the farm are vulnerable,” explains FFF board member Steve Saltzman, CEO of Lowcountry Development Corporation, a Charleston-based small business lender and community development organization. The funds raised from the Kickstarter campaign will change this. “Germaine has been phenomenal at raising money and creating a sustainable operation,” says Jennet Robinson Alterman, a consultant and former director of the Center for Women, where she met Jenkins years ago. “She’s definitely a local trailblazer in this field.”

Five years post pole-vaulting days, the farm employs five staff members, including Jenkins’s eldest child, Anik Hall, as special projects manager and son, Adrian Mack, as farm manager. They are in the final phases of purchasing the property and actively looking for other land on which to expand. Plans to create a new pavilion and farm kitchen on the Fresh Future Farm site are underway, which will enable Jenkins to host more education and outreach programs about nutrition, healthy cooking, and entrepreneurism. Chef Deljuan Murphy will not only be teaching classes but creating freshly prepared foods from the farm’s produce for customers to purchase. There’s already a wood-burning oven on-site, “for my baking,” says Jenkins.

Fresh Future: The successful “Claim Our Roots” Kickstarter campaign will fund expansion at the current site, including a new open-air teaching pavilion with solar panels and a mobile incubator kitchen. Jenkins plans to offer the FFF model as a free template for others to use in underserved areas across the Lowcountry and beyond.

Future Forward Farm

“Germaine’s passion and persistence make her a bit of a modern day prophet for equity and food justice. It’s remarkable what she and her board have been able to accomplish,” says Bill Stanfield of Metanoia, on whose board Jenkins once served. Her accomplishments have received national attention as well, including being the inaugural recipient of the Slow Food Alliance’s John Egerton Prize in 2018, an award that recognizes those “whose work, in the American South, addresses issues of race, class, gender, and social and environmental justice, through the lens of food.”

Jenkins is quick to credit her staff and her network of customers, volunteers, and supporters: “I’m most proud of the fact that working class community members did all of this—work that is getting national recognition,” she says. “Our organization’s greatest strength is that everyone who works for us has either used EBT benefits or shopped at food pantries; I’m not the only one.”

Jenkins’s vision for FFF has never been just about food, but a collaborative, regenerative movement that also nurtures economic empowerment. By employing people from the neighborhood and paying living wages, FFF teaches job skills and generates economic power to be reinvested back into an underserved area.

“We are each others’ support system at the farm,” says Jenkins, who often cares for her granddaughter while working in the store. “I graduated with honors but didn’t have childcare, so I was technically poor with all this education. Fresh Future Farm was the kind of job I needed when I was a single mom at Johnson & Wales. I’ve told our board that we need to offer wrap-around services, like housing support and childcare. Fifteen dollars an hour doesn’t go far when rent and taking care of kids is so expensive.”

Despite this summer’s Kickstarter success, funding for future growth remains a challenge and a priority. Sales from the grocery store cover restocking the shelves, but nothing more. Most funds come from private donors, including the “Claim Our Roots” campaign that tees up expansion. “When we identify a new space, we’ll identify our workforce from neighborhoods around that space, just as we’ve done here,” she says. Ultimately, Jenkins plans to offer Fresh Future Farm’s model as an “open source template” for others to utilize in other underserved areas across the Lowcountry and beyond.

Growing Wealth

Seeing the impact Fresh Future Farm has already had in the Chicora-Cherokee community keeps Jenkins motivated. A couple of her regular customers are legally blind, including a Hispanic man, who lost his sight because of diabetes. “He told me if we had been here three years earlier, he would have been able to eat healthier, manage his diabetes, and wouldn’t be blind,” she says. “We are providing high-quality, nutrition-dense food to people who are more likely to have diabetes and high blood pressure. Those are health problems we can fix.”

Additionally, last spring, Fresh Future Farm planned and hosted South Carolina’s first Black Farmers Conference—another part of Jenkins’s vision to build the network of people who love the land and are empowered to grow community. “We definitely embrace a micro-entrepreneurial focus,” she says. “It takes an entrepreneurial mind-set to get out of poverty. We want people who work with us to leave the farm and start their own business—that’s the only way to grow wealth.”

Walking through the farm rows, Jenkins says, “I’m also super proud of the fact that all our stuff tastes way better than anything you get anywhere else. This is my favorite herb,” she mentions, as she plucks a bit of zingy Mountain Mint. “Mustard greens are my favorite fall crop, and our peaches and loquats my favorite fruits.”

Her favorite FFF team member, though? That’s an easy call—grandbaby Sierra. “I didn’t know anything about growing fresh food until I was in my 30s,” Jenkins says. “My son, Adrian, started learning when he was eight, and now Sierra, who just celebrated her first birthday, is learning. She’s already eaten the best dirt in town.”