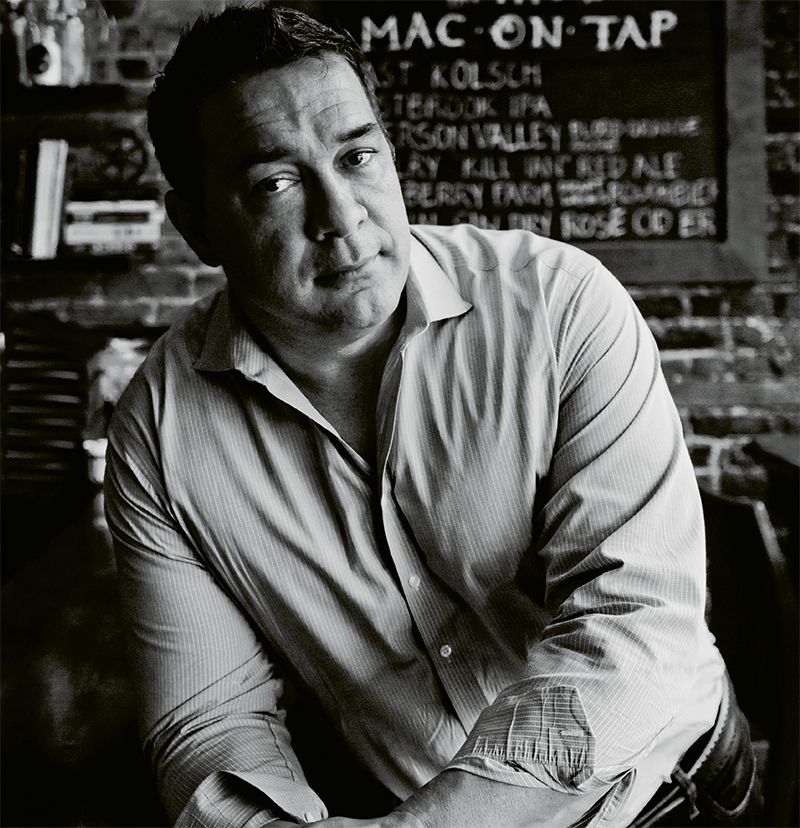

It’s hard to believe that the man who built the successful Indigo Road hospitality group—Oak Steakhouse, O-Ku, The Macintosh, and Indaco, to name just a few of its 18 properties in four Southern cities—was once crippled by alcoholism and drug abuse. Here, Steve Palmer shares his personal battle with addiction, how he was saved from an out-of-control spiral, and how he’s paying it forward to help others in the food-and-bev community, here and throughout the Southeast

Saturday, November 3, 2001

I’m lying facedown on my apartment floor. I have been told my liver is failing, and my body shakes as I hallucinate that things are flying out of the wall. My wife has just left me, and her last words, “As long as I stay here, you will stay sick,” are ringing in my ears. I am an alcoholic and a drug addict, a fact that I can no longer ignore.

I have done all the usual bargaining of “I’ll only drink wine... I won’t do shots... I will only smoke pot...” that all addicts propose when holding onto the last hope that we can still manage our lives. That’s the thing about the disease of alcoholism: It is the only disease that tells you that you don’t have a disease.

The hopelessness and desperation are all-encompassing, and I cannot see a life beyond this because it is all that I have known for 20 years. I have tried to quit time and again and have broken every promise I made to myself and others about “never again.” But the truth is that I cannot quit alcohol and cocaine. I have given up hope that my life will be anything other than this and realize that I am going to die.

On the outside, I appear successful: I am a certified sommelier with the job that I always wanted, running one of the top restaurants in the city. And I am dying. I know I need help, but I keep coming back to the fear that there is no way to work in Charleston’s restaurant business without drinking. I have never met anyone in this industry who doesn’t party. That is the ritual, after all: we work every night in a high-stress, high-adrenaline environment, and then we head out to do shot after shot of Grand Marnier and chase it with vodka to come down from the high. This is the life. This is the “normal.” This is the culture. I’m not sure when I crossed the line from just having fun to doing what I must in order to function, but I know with certainty that this is what I have to do to survive.

I lie on the floor shaking, knowing that alcohol has won. I realize there is absolutely nothing I can do to stop it anymore—this is my fate. I cry out, “God, unless you put me where I can’t get to alcohol, I am going to die.”

Monday, November 5, 2001

I walk into work at Peninsula Grill. It’s 10 a.m., and owner Hank Holiday has said he wants to meet with me. I’m nervous because I know I am spinning out of control, and I’m paranoid about who else may know how bad off I am. I walk in to Chef and Hank sitting together with somber looks on their faces, and my life changes in an instant. Hank informs me that I have a choice to make this second: I can go to rehab, or I can clean out my office. Every fiber of my being screams, “Go to hell!” All I can think about is getting a drink. I ask if I can go for a walk to think about things but am told no and to make my decision.

In that moment, I remember crying out just days ago, asking to be put in a place where I couldn’t get alcohol, and realize that it’s really happening. Call it divine providence or an answered prayer; either way it’s a miracle, and it’s my way out.

My disease is screaming in my ear, “Get out, go get a drink, get the hell away from these people!” But then I utter the words, “I’ll go to rehab.” I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired. I have no fight left in me, no more bargains to be made. I just want to stop hurting.

Tuesday, November 6, 2001

I am in rehab. Without drugs or alcohol in my body, 20 years of emotions come flying out. Memories of a broken childhood, of my dad—my hero—dying when I was only 10 years old, of being homeless as a teenager. They all come rushing out. I have no idea how I am going to return to Charleston to run a restaurant or if I will even have a job, but I have something I haven’t had in a very long time: I have hope. Something to hold on to. A belief that maybe there is a better life for me; perhaps this isn’t the end but only the beginning. I am not sure how I will remain in the business I love, but I know I am going to try everything I can to make it work.

Saturday, December 22, 2001

It’s my first night back at the restaurant, and I’m scared and unsure. The dining room fills up, and a server hands me a bottle of wine to open at a table. My body freezes, and a panic attack begins. Running out of the restaurant, I go to the roof of the Planter’s Inn, look up to the sky, and ask God, “How I am going to do this?” And a single word comes to me, a word that would go on to have so many meanings in my life. As I hear it, a great peace envelops me, and I know I am going to be okay. The word is “surrender.”

I realize in that moment that I have to stop fighting everything in my life. I have to stop fighting the fact I am an alcoholic, stop fighting that I am trying to get sober in the restaurant business. I have to surrender and accept that everything in my life leading up to this moment happened for a reason. I go back downstairs to begin my journey of being a sober person. I don’t know anybody else in my industry who doesn’t drink, but somehow, I know I am going to be alright.

Over the next few years, my gratitude continues to grow for those who helped me, especially Hank Holiday. He loved and protected me when I too scared and weak to help myself.

Friday, November 17, 2017

I have been sober now for 16 years. Sobriety is my life’s most precious gift, and it continues to leave me in awe. The path of sobriety has been a soul-wrenching, heartwarming journey of self-discovery. I have faced my darkest demons, my most painful childhood memories, and I have learned to make peace with it all. I have learned to accept and love myself, though I know that will be a lifelong process.

The most beautiful gift of being sober is the ability to love the restaurant industry in a way I could have never imagined before. My life is not less than because I quit drinking; my life is so much more. I’m not missing out; I do everything I ever wanted to do: go to concerts, go to dinner, and travel the world, only now with a deep appreciation for every bit of it.

During this time, Charleston’s food-and-bev community has changed immensely. I now have many brothers and sisters who walk the road of sobriety with me and who continue to love working in the restaurant business. This beautiful city that I call home looks more colorful and alive than ever. Watching sunsets on Sullivan’s Island, attending a Spoleto event, or simply walking the streets and witnessing Charleston on display have a meaning now, and I often can’t imagine how this could be my life.

Sobriety is not always easy, and I have seen many of my friends die over the years, the struggle to stay sober being just too much to bear. I have had many tough moments and have had to learn how to face life without hiding in a bottle. My sober mentor reminds me, “Steve, your disease is right outside doing push-ups, just waiting for your return.” After all this time, I know it would only take one drink and I would go back to the hopelessness, the sickness—and so I stay diligent. I remember that this gift is one day at a time and must be cherished and protected against all else. Nothing can be more important than my sobriety.

I sometimes have flashbacks, like when I took the stage at TEDx Charleston last fall to speak about this very topic. Everything stops, and I bounce backward and forward through time. I flash to being homeless, to sticking a needle in my arm, to being arrested, and then to what my life is now, and I often cry. I cry with wonder, with awe, and with overwhelming gratitude that this is the life I now get to live. I weep with profound joy that I was given this gift that so many other addicts will never know.

I’m grateful for the 12-step community of support in my life—amazing souls whose only desire is to help people stay sober. The bond of shared purpose is truly inspirational. Learning that we can manifest the life we want if we are willing to listen and do the work is one of the most powerful truths that sobriety has brought me.

I look around at the dedicated individuals of The Indigo Road and wonder how I ever got so lucky to work side-by-side with these people. These are the moments that stop me in my tracks, and quite frankly I am speechless.

Ben’s Friends

The restaurant business is a giving business. Chefs donate their time and talents for countless fundraising events; we mentor young aspiring chefs; we go to schools to teach nutrition. Yet the answer to how I was going to give back in a personal way had alluded me—that is, until a couple of years ago when my friend Ben Murray tragically gave me the “how and why.”

Ben was a happy-go-lucky chef whom I met in 1995 while opening Canoe in Atlanta. He reminded me of one of the guys in the Rat Pack—always cutting up and laughing with a drink in hand. He was a kind soul who saw the best in every person and every situation. We lost touch over the years, but after reconnecting in 2016, I called him in Atlanta and asked him to help me open a restaurant in Florence, South Carolina.

Ben worked tirelessly for six weeks, often 16 hours a day. When he failed to show up to work a few times, I became worried. I went to Ben’s hotel room, and he wouldn’t open the door. Not wanting to create a scene, I left. Ben shot himself in that hotel room and died alone. When I called his mother to explain what happened, I learned that Ben had been in detox six times but never grasped sobriety. The irony of our opening night was that there were four sober people working alongside Ben, and yet he felt like he couldn’t ask us for help—he just couldn’t ask.

Heartbroken with grief would be an understatement. I knew it was time to fight back against addiction in our industry. I went to my dear friend and fellow sober person Mickey Bakst, the GM of Charleston Grill, for help. In October 2016, we started “Ben’s Friends,” a support group in Charleston specifically for people in the restaurant industry who are struggling with addiction. We meet weekly to offer support and resources to the Bens of the world who have run out of hope. The people I have met at those meetings fill my heart in a way nothing else ever has or ever will.

Ben’s Friends launched in Atlanta last February and in Raleigh in April. The industry I love is finally starting to address this issue, which makes me smile. This city I call home has loved me at all moments of my life, has welcomed me and wrapped her arms around me in a way that I could never repay. But I know I will spend the rest of my life trying. This “Holy City” has been my salvation and my protector when I couldn’t protect myself. Being sober here in Charleston has given me a purpose that I never thought I would have, and for that I will always be grateful.

Founded by Steve Palmer and Mickey Bakst in 2016, Ben’s Friends is a food-and-beverage industry support group “offering hope, fellowship, and a path toward sobriety for those struggling with substance abuse and addiction.” The nonprofit organization meets every Sunday at 11 a.m. at The Cedar Room (701 E Bay St., Suite 200) and Thursdays at noon at Indaco (526 King St.). For more information or to donate, visit bensfriendshope.com.

Watch - Sober reality for the food and beverage industry | Steve Palmer | TEDxCharleston

Portraits by Peter Frank Edwards, additional photographs courtesy of Steve Palmer