Learn about the transformative projects and where they stand today

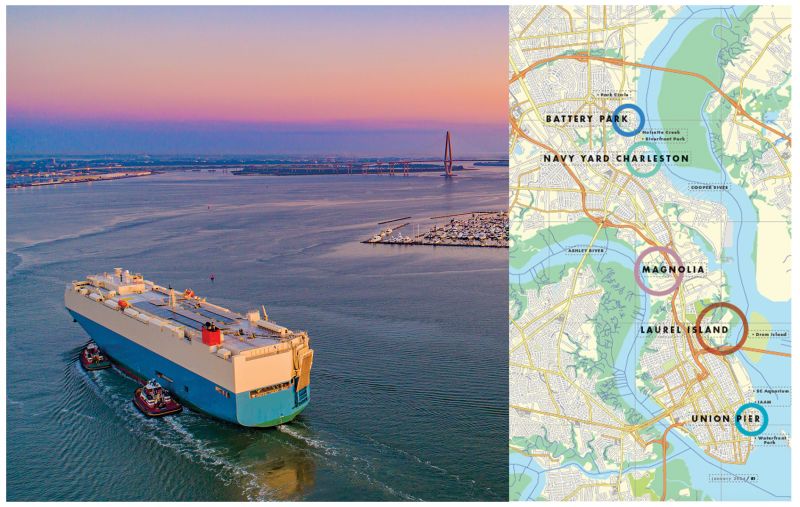

Ever since the voyagers on the sailing ship Carolina slipped up the Ashley River in 1670 and founded Charles Towne, the Holy City’s rivers have been its lifeblood. For more than 200 years, the then-bucolic Ashley and Cooper provided passage for vessels laden with indigo and rice, but 20th-century industrialization left much of their banks contaminated wastelands. Now five huge riverfront redevelopment projects promise to transform vast tracts of abandoned shipyards, shuttered mills, and landfills into parks, homes, shops, and offices, filling the shoreline of our venerable rivers with a lucrative commodity—people.

In Charleston, two projects—Magnolia and Laurel Island—could bring thousands of residents onto what was once one of the South’s most contaminated industrial sites and a former garbage dump. A third and perhaps the most notable project—a reimagined Union Pier—would turn docks, lots, and warehouses into a new waterfront district, building on the momentum of Joe Riley Waterfront Park, the South Carolina Aquarium, and the new International African American Museum.

In North Charleston, ambitious redevelopment plans along the Cooper River promise no less than a brand new city. From the sprawling former naval yard, city leaders envision building a downtown from scratch, spreading from Park Circle down the riverfront. “This is a clean slate to create a big city downtown that North Charleston has never had,” says Ryan Johnson, the city’s economic development director.

The redevelopment of these challenging mega-sites has been and will continue to be slow. Billions of dollars are at stake. Top planners are massaging the plat maps. Concerns abound, from stormwater management and flood control to viewshed preservation and affordable housing. All these moving parts mean deliberate progress for these large projects, notes Robert Summerfield, Charleston’s planning director. “In 2023, we like instant gratification, but these are significant investments,” he says. “They are 20- and 30-year build-outs, done in phases. And it’s taken a lot of work to get them where they are now.”

For the start of the New Year, we put together an overview of these potentially transformative projects, the players involved, and where they stand today:

After the Union Pier redevelopment plan by California-based Lowe group was met with public outcry last fall, SC Ports ended that agreement at a cost of $9.9 million and pivoted to a community-led planning process managed by the Joseph P. Riley Jr. Center for Livable Communities at the College of Charleston. In November, the center with its local stakeholders committee selected design firm Sasaki, which created Waterfront Park, to reimagine the nearly 70-acre site as a mixed-use development more in keeping with the Charleston Historic District.

Union Pier

The SC Ports Authority has been marketing the pier—minus the cruise ship terminal—to developers since about 2019. Various attempts to sell have not panned out. Most recently, a plan by the California-based Lowe group cratered after public concerns surfaced ranging from shoreline stabilization and stormwater issues to population density and the height of buildings.

SC Ports ordered a reboot and tapped the College of Charleston’s Joseph P. Riley Jr. Center for Livable Communities to work with a local stakeholder advisory committee to select a designer and manage public input. In October, design firm Sasaki, which in the 1980s redesigned the port’s property south of Union Pier into what is now Waterfront Park, was chosen. The firm, headquartered in Boston, has tackled some of the state’s most significant projects, including the master plans for downtown Greenville and the expansion of USC’s urban campus in Columbia. But its reach stretches globally from designing Saigon’s riverfront in Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City to building the urban design framework for Kabul, Afghanistan.

The Riley Center, formed in 2018 and named for former Mayor Joe Riley, will be the conduit between the public, stakeholders, SC Ports, and the city in forging the Sasaki plan. “We’re the connective tissue,” says Riley Center assistant director Ali Moriarty.

Sasaki is expected to deliver a new vision for Union Pier to Charleston City Council this summer. The firm will use the Lowe plan and other resources to design a district that will attempt to soothe public concerns, dovetail with the city’s waterfront stabilization strategy, and create gathering spaces and more access to the harbor. “Clearly the time for that area as an active industrial port has passed,” Summerfield notes. “We want a good redevelopment plan for the community to re-engage with the water. It’s important we get it right.”

UNION PIER

Owner: SC State Ports Authority

Developer: To be determined

Location: 10 parcels from Lauren Street to Waterfront Park from East Bay Street to the harbor

Size: About 70 acres including seven acres of wetlands and 20 acres of docks and piers

Timeline: A new development plan is expected this summer.

Learn more: unionpiersc.com

Plans for Laurel Island approved in 2020 include a mix of residential, retail, hospitality, and office space, as well as public parks, an outdoor concert venue, and access to the harbor.

Laurel Island

Located at the mouth of the Cooper River at the foot of the Ravenel Bridge, Laurel Island, a former landfill, is one of the city’s most desirable and promising tracts.

The site hosted the Rumney Distillery in the 1790s, hence the name Rumney Street (now Romney) for its main access point. It later served as a state armory during the Civil War, then was abandoned infill and marshland before ultimately becoming a landfill in the 1960s. In 2003, Philadelphia-based developer Lubert-Adler bought the property with aims to build a resort, a plan ultimately scrapped. Since then, multiple entities have eyed the property but decided to move on.

In 2020, a proposal by Atlanta-based LRA Promenade LLC and local partner, CC&T Real Estate Services, for a mixed-use development was approved by Charleston City Council. “It’s got views to the north, south, east and west,” says Robert Clement, of CC&T. The plan calls for about 4,000 residential units including affordable housing, 400 hotel rooms, a park, and substantial office and retail space. However, those levels can change depending on traffic impact.

A special tax district will help finance a future development. Once all governmental agreements are in place, LRA may opt to put the property on the market, Clement notes. Summerfield confirms that the agreements would pass to new owners. “The who is not as important as the what,” he says.

LAUREL ISLAND

Owners: LRA Promenade, LLC and

LRA Promenade North, LLC, Atlanta

Developers: CC&T Real Estate Services

Location: North of Highway 17 and east of Morrison Drive and the railroad line

Size: 196 acres, including 31 acres of wetlands

Plans: 4,260 housing units, a 400-room hotel, 39.2 acres of public park, 276,500 square feet of retail, and 2.2 million square feet of office space

Timeline: To be determined; the tract may be placed for sale.

With the contamination remediation of this large Ashley River tract complete, Houston-based Highland Resources plans to begin development of its city center and waterfront park, with other phases following through approximately 2040.

Magnolia

The Magnolia site on the Ashley River in the peninsula’s heavily industrialized neck is the farthest along of the mega-sites—and was once its most polluted. The property was home to the Koppers fertilizer manufacturing and wood treatment plants, which contaminated the land for decades with arsenic, lead, and creosote. It was listed as a federal Superfund site in 1994, naming it one of the nation’s most dangerously contaminated tracts, and environmental cleanup began in 2002 on about two dozen parcels.

In October, the US Army Corps of Engineers declared the cleanup complete and green-lighted the site for vertical development, which is expected to begin this year. Owner and developers Highland Resources Inc. of Houston—whose projects of note include Highland Industrial Park, an 18,780-acre property in East Camden, Arkansas, and Marble Falls, a 5,000-acre mixed-use development being planned for West Austin, Texas—plans to knit a whole new neighborhood of more than 4,000 apartments and condos, a staggering one million square feet of offices and ample retail into the city’s collective. It’s expected to be built out in phases by 2040. “This project is huge,” Summerfield says. “Early American industrialization contaminated the area, and this project cleans that up and puts it back to productive use. It also provides [river] access for the entirety of the community that it hasn’t had for, technically, ever.”

MAGNOLIA

Owners & Developers: Highland Resources Inc., Houston

Location: Along the Ashley River north of Monrovia Street to Hagood Road and west of I-26

Size: 189 acres (49 acres of marsh)

Plans: 4,080 housing units, one million square feet of office space, 200,000 square feet of retail, and more than 1,000 hotel rooms spread over three or four hotels; a minimum of 24 acres of green space

Timeline: The site was released for development by the US Army Corps of Engineers in October, and the town center site plan is expected to be built in phases over the next 16 years.

Estimated Investment: $2 billion

Website magnoliachs.com

(Left) A bird’s-eye view of the former Charleston Navy Base, a shipbuilding and repair facility, which closed in 1996; (Right) Ships prepare for war at the Charleston Naval Shipyard in this photo dated July 24, 1941.

Navy Yard Charleston

In a city steeped in history, the Charleston Naval Base holds its own. In 1901, the US Navy purchased the former Chicora Park on the west bank of the Cooper River to build the South’s largest dry dock and shipyard. Expanded during World War I and II, the base employed more than 25,000 civilian workers. In 1972, the 10-story Naval Hospital was built, North Charleston’s tallest building. In the ’80s, the renamed Charleston Navy Base and its sister Naval Weapons Station hosted more submarines, destroyers, and cruisers than any base in the world.

The sprawling complex reached its zenith in 1982, employing 36,700. But in the 1990s, it was closed by the US Department of Defense as part of its streamlining Base Realignment and Closure process. City and state officials were stunned, and South Carolina’s largest employer had fallen by the wayside.

A city-backed redevelopment effort called the Noisette Plan begun 20 years ago saw limited success before its Noisette Company fell into foreclosure. Another plan to repurpose the Naval Hospital into Charleston County offices ended in bankruptcy, costing taxpayers $33 million.

Atlanta-based Jamestown—a global real estate investment and management firm with a resume including One Times Square and Chelsea Market in New York City, Ponce City Market in Atlanta, and Ghirardelli Square in San Francisco—and its partners plan to overhaul the 85-acre site into a mixed-use neighborhood. Two of the warehouses along Storehouse Row are being transformed into apartments set to open in May and renovation of the Naval hospital into apartments is also expected to begin this year.

Navy Yard Charleston

Owners: Navy Yard Charleston

Developers: Atlanta-based Jamestown; local WECCO Development (led by Lucile and William Cogswell, Charleston’s new mayor); and Atlanta-based Weaver Capital Partners

Size: 85 acres, 12 buildings

Plans: The most recent iteration includes 3.5 million square feet of offices, homes, shopping, and dining near the Park Circle neighborhood, as well as new green spaces, a concert hall, and an outdoor events venue.

Timeline: To be determined

Website: navyyardcharleston.com

Although no specific plans are set for Battery Park, last year the Urban Land Institute selected the site for its annual Gerald D. Hines Student Urban Design Competition. There were four finalists, including the “Port Unity” proposal by a team of Harvard students, generating a wealth of ideas for development.

Battery Park

Last spring, Jamestown was also tapped to serve as master developer for the north end of the former naval base from Noisette Creek to Molly Greene Way. The city owns 50 acres of vacant land with some structures that will likely be demolished. The US Air Force has the remaining 20 acres, with facilities that will eventually be relocated to Joint Base Charleston.

North Charleston officials envision a high-density development with a city center feel to be built over 10 to 20 years. “There is no timeline, but all the right folks are talking. There is momentum,” says North Charleston economic development director Ryan Johnson.

A master plan calls for mid-rise residential development at a minimum of 46 units per acre—with no maximum as yet—in addition to parks, shops, and walking trails. It is connected to the popular Riverfront Park to the south by the striking 800-foot curvilinear pedestrian bridge over Noisette Creek, which was completed in 2022. The development would knit closely with the Park Circle and Navy Yard efforts to form a central downtown for North Charleston. “There’s a lot of synergy going on,” Johnson adds.

A competition by the Urban Land Institute for graduate and post-graduate students at universities across the nation yielded a wealth of ideas, but a concrete development plan has yet to surface. “We want a true mixed-use downtown development for that property,” Johnson says. City officials would also like to see the area between Battery Park and I-526 redeveloped to connect the Navy Base to East Montague Avenue but realize that will take time, he notes.

BATTERY PARK

Owners: City of North Charleston and

the US Air Force

Developers: Atlanta-based Jamestown

Location: Along the Cooper River, north of Noisette Creek to Molly Greene Way

Size: 70 acres

Plans: A master plan calls for a minimum of 42 units per acre of residential development including parks, and shops, as well as walking and biking trails.

Timeline: To be determined