A tale of a prized, bygone gobbler

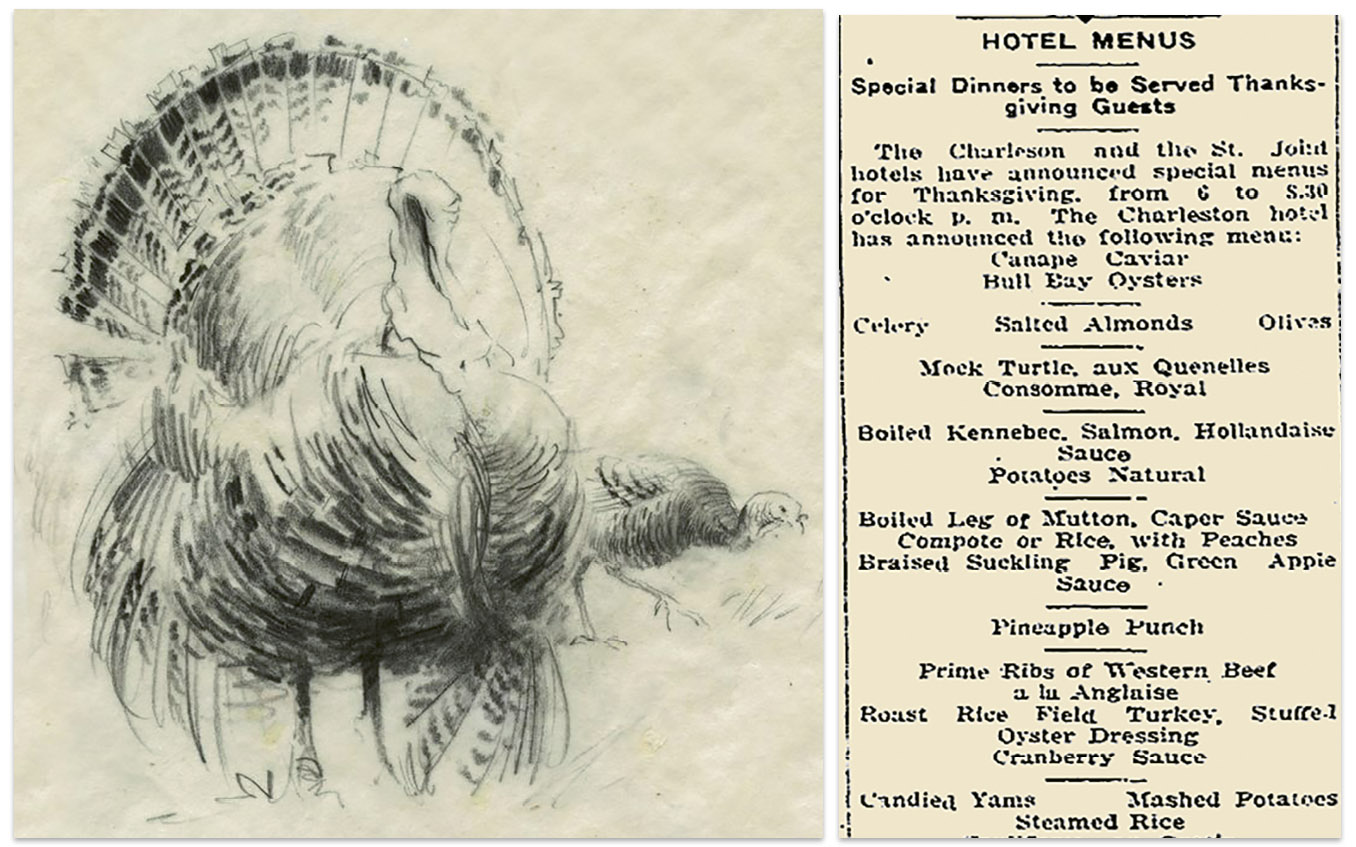

The Charleston Hotel featured rice-field turkey on its Thanksgiving menu, as advertised in the Charleston Evening Post in 1920.

“If there is any better wild game than a rice-field wild turkey, stuffed with peanuts, circled with browned sweet potatoes, and fragrant with rich gravy...I’ll follow you to it.” So rhapsodizes Archibald Rutledge—the South’s foremost writer of hunting tales during the early 20th century—in the sporting journal Outing (1919). A century later, no game dish holds more mystique in the Lowcountry than this curious free-roaming bird.

The rice-field turkey came to be by feeding on the carcass of the Southern rice industry. On the precipice of World War I, the Carolina rice planting world crashed; plantation after plantation ceased cultivation due to financial reasons, storms, or the deaths of old planters. Rutledge notes in “The Wrong Gobbler,” published in Field & Stream (1941): “Here on the Carolina coast, along the great delta of the Santee, vast areas of former rice-lands are overgrown to white marsh, duck oats, wampee, wild rice, smartweed, and other aquatic foods. In almost impenetrable cover like this most of our turkeys spend the day.”

The fowl, fattened on their peculiar Lowcountry diet while roaming abandoned rice fields, soon became a prized protein. The rice-field turkey first appeared on a public event menu in 1906 (published in The Evening Standard) and was the invariable centerpiece of many a holiday dinner from 1895 to 1930. The 1920s marked the heyday of its cult, when Thanksgiving, Christmas, or New Year’s feasts could not command respect without the wild bird on the bill of fare.

(Left) A drawing of a rice-field turkey, circa 1900; (right) The Charleston Hotel's Thanksgiving menu, as advertised in the Charleston Evening Post in 1920.

Though distinct flavor distinguished these turkeys from poultry raised en masse in confined feedlots, in the late 1920s, heavier, plumper breeds, shipped from out of state, began to flood American grocers. By the mid-1930s, the Carolina’s coastal zone had evolved from watery fields into forested swamp and bog, causing the rice-field turkey to peter into obscurity—though not without grievance. As one journalist lamented in a 1936 newspaper article entitled, “The Price of the Gobbler”: “Charlestonians and other South Carolinians will eat for Thanksgiving dinner many turkeys which come from other states, for South Carolina does not produce enough turkeys for its own demand...it is much better for the South Carolinian to buy a South Carolina turkey. If he can get a ‘rice-field’ turkey, he will come into a bird of superior flavor...”

Indeed, one would not be advertised in the Charleston, Savannah, or Wilmington markets after Thanksgiving 1936. Only a select few who kept rice growing on private fields could savor such rarities, never sold to strangers. And so it was that the rice-field turkey receded into the realm of legend.

Images courtesy of (menu & turkey) David Shields & (Charleston Hotel) South Carolina Library of Congress