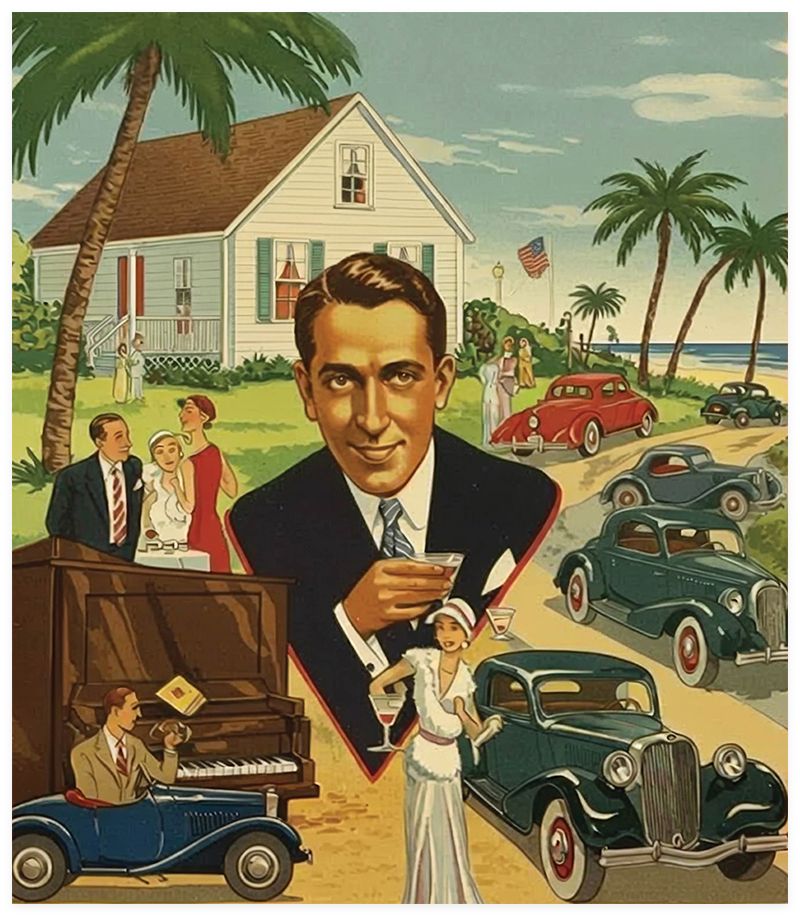

A legendary tale of a glamorous party in 1934, when the famed composer introduced the music for Porgy and Bess

In a world often filled with skepticism, the family stories passed down through generations carry a weight that is hard to dismiss. Over the decades, my parents, Harry and Fannie Berendt, often would recount a strange, serendipitous beach experience from their youth. Although 90 years have passed and there is no one who can corroborate their encounter, it always felt undeniably true to me. My mother and father were good people grounded in reality and not prone to lies or exaggeration. This story is theirs; the embellishments are mine.

In 1934, my parents, who lived downtown on Montagu Street, rented a cottage for a week-long vacation on Folly Beach. During that decade, Folly had not achieved notoriety as the lively, funky “Edge of America” we know today. It served as a serene and secluded haven, where the rhythms of nature dictated the pace of life and provided solace to its residents and visitors.

On that memorable summer afternoon, Dad was rehearsing a violin piece for an upcoming concert. (Although an amateur, he was an accomplished, versatile musician, equally skilled in performing classical piano sonatas, jamming improvisational jazz, and playing violin in the Charleston Symphony Orchestra). A knock on the door interrupted his concentration.

When my mom answered, she was taken aback by a splendidly dressed, courtly gentleman, who introduced himself simply as “D. H.” He said that his associate, who was renting the house next door, was captivated by my father’s music and wished to extend an invitation to attend his party that night. When asked who his associate was, D. H. smiled demurely and stated, “Please join us,” then left without another word. To say the least, my folks were intrigued. Unknown to them, this night would be unforgettable, not just for its grandeur, but for the magic that awaited them.

Beach Bound: Charleston author, poet, and playwright DuBose Heyward (right) on the Folly Beach ferry, circa 1920

That evening, they crossed the threshold of their humble cottage and found themselves enveloped by a world that was utterly fantastical. Before them, West Arctic Avenue pulsed with life. Sleek, chauffeur-driven roadsters and elegant chromed convertibles, having been transported from the mainland by ferry, were being parked along the modest street. From the gleaming vehicles emerged glamorous women attired in exquisite Art Deco-inspired dresses of linen and chiffon and men sporting colorful pastel suits topped off with white straw hats. The entourage of couples chatted animatedly as they strolled, hand-in-hand, on their way to what was, obviously, a grand affair. My parents, adorned in their brightly colored beachwear, felt like out-of-place country bumpkins, thinking, “Toto, I don’t believe we’re in Kansas anymore!” Still baffled as to the identity of their mysterious host, they wondered who could possibly attract guests of such opulence and style to unpretentious, li’l ol’ Folly Beach.

Upon stepping through the door to the soiree, they were greeted by their earlier visitor, the enigmatic D. H., who welcomed them effusively, exuding genuine warmth. They immediately were drawn to an otherworldly piano performance wafting through the air. Following the beckoning sound, they weaved slowly through clusters of glitterati whose laughter and clinking glasses blended into a distant hum. The music was on one hand familiar, yet unlike anything Dad had ever heard. Songs, rich and complex, blending classical, jazz, and blues genres with African American spirituals and Jewish liturgical influences. Then, in that moment, he recognized the unmistakable style, rhythms, and harmonies. Excitement bubbled within him.

My parents moved closer to the music, then caught sight of an upright piano surrounded by a tightly packed group of admirers obstructing their view of whoever was playing with such depth and passion. Dad stood transfixed, the world around him fading away, inexplicably connected to the music. As the performance reached its climax and the final note lingered in the air, the crowd erupted in applause. Feeling a tap on his shoulder, my father glanced around to see D. H., his face beaming broadly. “My friends, allow me to introduce you to George Gershwin!”

My father was awestruck; the reality of the moment was surreal. How could this internationally acclaimed genius, who literally redefined the music of a nation, be present here at this ordinary beach house on Folly?

As if on cue, D. H. continued enthusiastically, “My name is Dubose Heyward. George is visiting the Lowcountry to compose Porgy and Bess, a new opera set in Charleston that has been adapted from my novel, Porgy.” (Little did they know that the opera soon would explode across the United States, forever changing the landscape of American music.)

Island Time: Brooklyn-born composer George Gershwin arrived on Folly Beach in June 1934 for a six-week stay to create the score for Porgy and Bess. (Right) A watercolor and ink sketch of Gershwin’s beach cottage by his cousin Henry Botkin.

Dad, giddy with excitement, and Mom eagerly tagging along, joined Gershwin and other musicians and artists in a lively discussion about the evolution of music within the cultural context of the 1930s. Although no one knew him, my father was accepted as part of a group of influential artists sharing ideas and collaborating to foster creativity and progress in the arts. The famed composer, charismatic and approachable, put everyone at ease. As the night unfolded, the party atmosphere continued, including impromptu performances, laughter, and camaraderie.

Later, the crowd began to disperse, and the guests’ chatter faded into the background, leaving my father engrossed in conversation with Gershwin. A bond had been forged between the two. When the clock ticked closer toward midnight, the room grew quieter until only my parents and their host remained.

Suddenly, Gershwin jumped up, startling Mom and Dad. With a mischievous glint in his eyes, he beckoned them to the back porch. Amid the crashing waves and the humid breeze, he leaned on the porch railing, pulled a lit cigarette from his lips, and tossed it into the sand.

(Now, dear reader, you’ve reached the point in which Gershwin, an icon who illuminated the shadows of musical mediocrity with his artistic brilliance, articulated an unexpected, bizarre request, proving that fact, truly, is stranger than fiction). “Would you mind?” he asked, glancing at my mother with an inviting, unreadable smile. “Step on that cigarette for me.” My mom was puzzled but complied, her foot gently extinguishing the glowing ember. Realizing what she had done, she thought to herself, “This arrogant jerk’s immense talent is exceeded only by his even larger ego!”

But then Gershwin’s expression changed from playful to contemplative. He said earnestly, “My friends, I wish you both a happy, long life and hope you share this moment with your children and grandchildren.” His words hung in the warm air like a sweet melody. My parents, who were newlyweds, exchanged glances, both touched and bewildered by the gravity of his request.

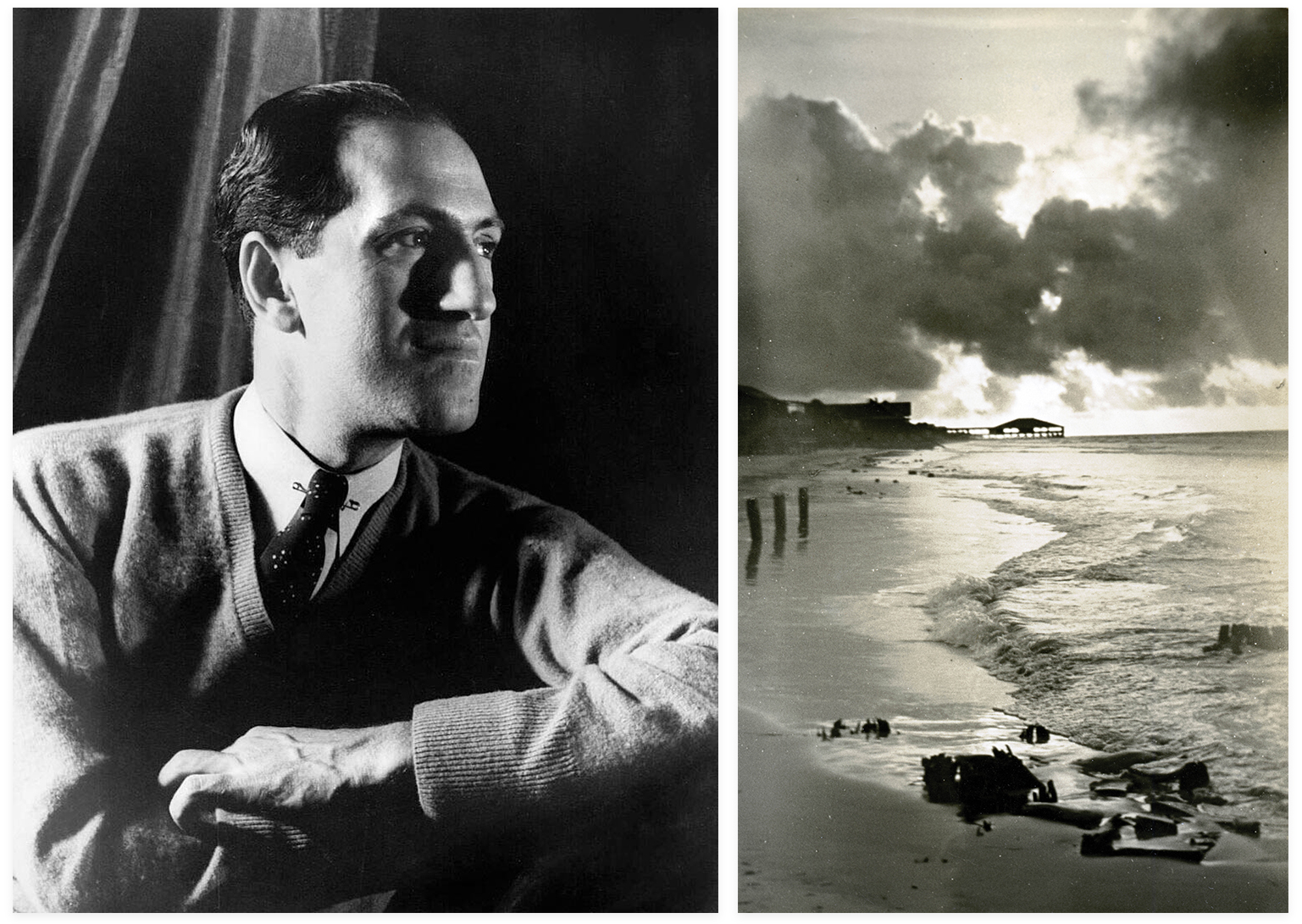

(Left) George Gershwin; (Right) A moonlit beach on Folly, circa 1930s.

What did he mean? In that brief moment, Gershwin seemed to impart a wisdom that transcended time, connecting generations with a single act. “Music, like life, is about legacy,” he continued, his voice softening. “Every note we play, every moment we share, is a part of something greater. You’ll carry this moment with you, just as I will carry the music in my heart.”

As they stood together, embraced by the infinite, moonlit horizon, my mom felt the weight of his words. It was a simple, ambiguous act, yet it felt monumental, a gift of perspective she would share through her lifetime. While the decades rolled by and the memory of that enchanted night lingered, Mom wistfully would often recount how she had snuffed out George Gershwin’s cigarette. She framed it as a moment of sublime serendipity—a reminder that life is fleeting, and sometimes, our most extraordinary and cherished experiences can occur when we least expect them.

And so, the legacy and mystique of that encounter continues, told through stories and the enduring love for the art that brings us all together.

A Charleston native, Ira Berendt attended the University of South Carolina and graduate school at UNC-Chapel Hill. A retired insurance broker, he was proprietor of This End Up boutique in Ashley Plaza Mall. Ira has been a member of the Charleston Men’s Chorus, Exchange Club of Charleston, and the executive board of Charleston Stage. He and his wife, Andrea, who have two sons, four grandchildren, and a great grandson, live in West Ashley. Ira expresses his heartfelt appreciation to Charleston magazine for featuring this story, marking his writing debut at age 82. His bucket list is complete!

Check out our Porgy and Bess playlist:

Listen in as Gershwin presents the music of Porgy and Bess on July 19, 1935:

Illustrations by Melinda Smith Monk/shutterstock.AI; photograph courtesy of Ira Berendt; courtesy of (Harry Berendt) Ira Berendt & (Ferry Passengers) The Charleston Museum; courtesy of (Porgy and Bess with George, Near Folly Island by Henry Botkin, watercolor & ink on paper, 1934) Gibbes Museum of Art & (Gershwin) the family of George Gershwin; courtesy of (men at piano) South Carolina Historical Society; courtesy of (watercolor) Marc Gershwin & (Gerswhin) wikimedia commons; & courtesy of (beach) the Charleston Museum