What the barrier island’s rebounding flora and fauna can teach us about our fragile yet resilient coast

The Caretta barely makes a ripple as she slinks out of Awendaw’s Garris Landing. The 50-seat ferry, named for the South Carolina state reptile and the endangered sea turtles that nest on Lowcountry beaches, is relatively empty on this muggy June Saturday as we begin a 30-minute cruise to Bulls Island. It’s midday, and most adventurers opted for the morning excursion “to beat the heat and get a full day on the beach,” explains Annie Owen, the Coastal Expeditions naturalist who manages the outfitter’s Cape Romain tours. Thankfully, the breeze is glorious as we pick up speed and begin winding our way through serpentine waterways.

“You’re now in one of only three Class 1 Wilderness Areas along the East Coast,” Owen explains as unfathomably green Spartina and cordgrass cradle the estuaries. “That means this 25,000-acre stretch of salt marsh within the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge is basically the same today as it was millions of years ago, the most pristine condition of any wildlife area, completely untouched by humans.”

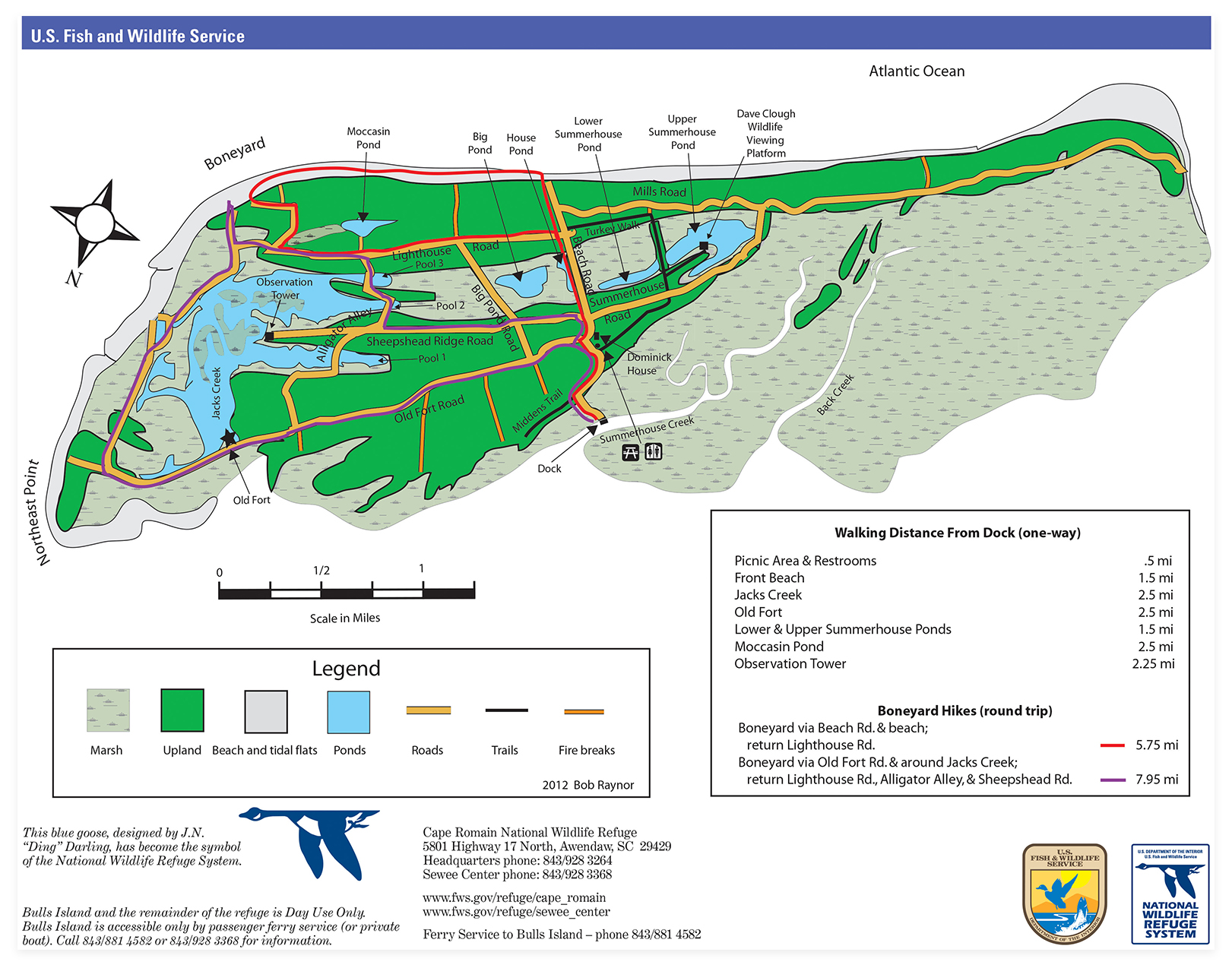

Twin Isles: If you superimposed a map of neighboring Isle of Palms over that of Bulls Island, the two are nearly doppelgangers. “The difference is one is fully developed, leaving nowhere for beaches and marshes to naturally migrate,” explains Annie Owen of Coastal Expeditions, which runs the ferry service from Garris Landing in Awendaw. The journey itself is a 30-minute ecotour, and upon landing, visitors can explore 16 miles of trails and seven miles of shoreline for a half or full day.

Indeed, the air smells salty and clean; a dolphin’s well-timed puffy exhale off the boat’s starboard puts an exclamation mark on her point. As far as the eye can see, sun glints off the water as endless prairies of marsh grass crown the pluff mud. Gulls swoop, pelicans glide, and around the next bend, orange-beaked oystercatchers poke around the low-tide line. In no time, the crowded mainland, with Highway 17’s knotty traffic and North Mount Pleasant’s big box stores, feels worlds away.

Owen’s boss, Chris Crolley, is a Bulls Island expert. He’s been making this boat trip regularly since 1993, when the Camden native and budding naturalist placed a wild bet on wilderness and took over the then-foundering ferry operation. Today, as cofounder of Coastal Expeditions and president of the Coastal Expeditions Foundation, he oversees a thriving enterprise dedicated to “putting people in the path of beauty” and exposing young people to the area’s natural wonders—or, as he likes to quip, “No kid left dry.”

The estuary is deepest at Turtle Creek, explains Crolley as we make headway toward the Bulls Island landing. “This is where loggerhead sea turtles proliferate, where they come in to feed and mate in springtime,” he notes. The three barrier islands that make up Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge—Bulls, Lighthouse, and Cape—will see some 60 turtle nests a day during nesting season, making it the most significant nesting site on the East Coast north of Florida. To ensure its protection, the Coastal Expedition Foundation funds two wildlife technicians to monitor for eggs and activity.

Crolley’s passion for all things wild is as clear as the Carolina blue sky on this summer day, and Bulls Island—with its dramatic Boneyard Beach, throngs of alligators, robust ecological diversity, and miles of undisturbed paths—is one of his favorite places to share that passion and educate others about the vital role that barrier islands and salt marsh estuaries play in our coastal ecosystem. But Bulls Island is also where, on the night of September 21, 1989, the Category 4 Hurricane Hugo slammed into South Carolina, obliterating the island’s mature maritime forest and causing severe erosion and damage. Now 35 years later, the island, a geological mirror image of the nearby but fully developed Isle of Palms—nearly identical in shape, size, and orientation—is a living laboratory for observing how natural systems respond after a catastrophic event. Has Bulls Island fully rebounded, or is there lasting impact? What was the effect on wildlife? And what can we learn from this barrier island regarding preparing and protecting our coastline for future storms, sea-level rise, and other impacts of global climate change?

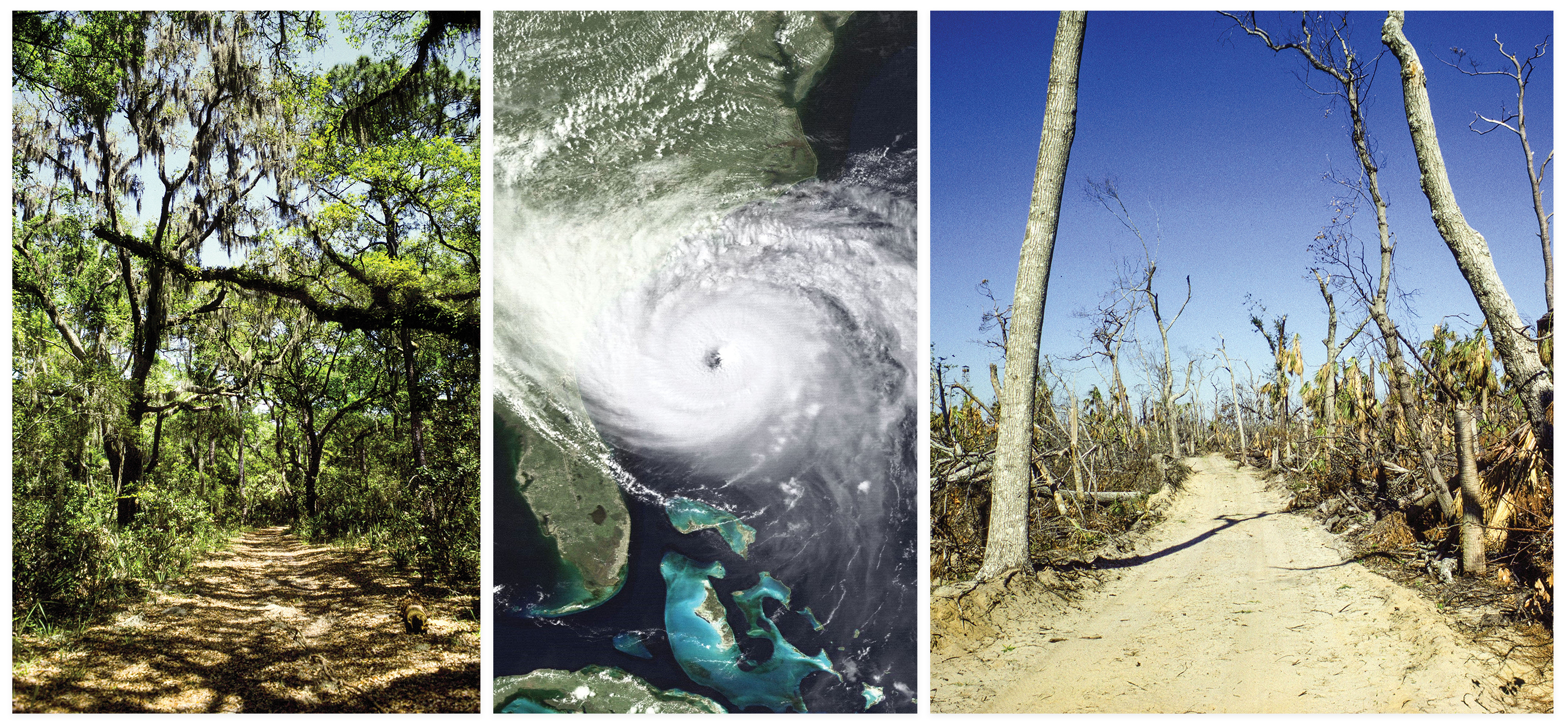

(Left to right) March 1989: Six months before Hurricane Hugo; Bull’s-Eye, Almost: A satellite image of Hurricane Hugo’s approach of the southeast coast as a Category 4 hurricane, on September 21, 1989, at 4 p.m. Its path to the left of Bulls Island delivered the brunt of the storm’s sometimes 200-mile-per-hour winds and 21-foot tidal surge to Bulls Island, as well as nearby Awendaw and McClellanville; March 1990: Six months after Hugo.

As we pull up to the Bulls Island dock, Owen points out a fire tower rising above the treeline. “Back before Hugo, you couldn’t see it. The mature maritime forest was as tall as that tower, making it hard to spot,” she says. It was what biologists call a “climax maritime forest,” a dense tangle of 23 different tree species with the most prevalent being Southern magnolia, live oak, cedar, palmetto, loblolly pine, wax myrtle, and red bay. Given that many of the loblollies were at least 80 years old, according to a 2005 Forest Ecology and Management paper, it seems that Bulls, prior to Hugo, had been untouched by major storms for nearly a century. “I’m so glad I got to witness that magnificent island with its mature maritime forest,” says Sarah Dawsey, manager of the Cape Romain Wildlife Refuge since 2011, who worked as a temporary biology technician with the refuge in 1989, focusing mainly on sea turtles. “Every road on the island was densely tunneled. It was just gorgeous.”

Hugo barreled in with 140-mile-per-hour sustained winds and gusts up to 200 and flattened Bulls Island with a 21-foot saltwater wave “that completely scoured it,” says Dawsey. “It still hasn’t regained the elevation it once had, which leaves the island more susceptible to erosion and saltwater intrusion,” she explains.

The pines were completely wiped out, but nearly 90 percent have come back, she adds, thanks to a healthy seed population. “The forest was full of pine trees with bark scales the size of dinner plates; two of us would have to reach our arms around the trunks to touch. But after Hugo, you could see straight through the island from the estuary to the ocean,” notes Crolley. “There’s nowhere you can go on this island where you don’t see evidence of [Hugo]. See this grand oak that’s missing that limb up there? All of the grand oaks have wounds from the storm.” Scientists called Hugo a catastrophic botanic event and projected that it would take another 100 years for Bulls Island to reach climax maritime forest status again.

Despite the destruction, Hurricane Hugo “wasn’t good or bad, it was just nature doing what nature does,” says Crolley, echoing his mentor and friend, the late Rudy Mancke, the beloved South Carolina naturalist and cohost of SCETV’s NatureScene, who filmed numerous segments and led nature tours on Bulls Island. During a 1995 visit to the island, Mancke noted the dramatic changes and damage, but without layering anthropomorphic judgment. “You see the skeletons of trees, dead pines everywhere, but look up there, a gangly great blue heron is making a nest [at the top of a dead tree],” Mancke said. “Things get changed. Nature doesn’t throw up her hands and walk away; things come back, slowly but surely.”

Change is the very nature of barrier islands, those ephemeral, ever-eroding and -accreting, always shifting land masses that Duke University coastal geologist Orrin Pilkey calls “restless ribbons of sand.” Hugo unquestionably took a toll on Bulls Island, which, along with Cape and Lighthouse islands, has lost land mass in the intervening years, according to Dawsey. Her concern is how sea-level rise will further impact these islands and their critical role as nesting habitats for sea turtles and migratory shorebirds. “Hugo was a catalyst for what we’re seeing today; it just leveled Bulls, Cape, and Lighthouse [islands]. It was really unbelievable,” she says. “Since then, with the increase in sea-level rise, the islands get flatter and smaller every time they get breached.” A December 2023 storm breached Jack’s Creek and the impoundment on Bulls in two places, reducing the freshwater habitat for alligators and wintering waterfowl by more than two-thirds.

In the Wild: The Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, which includes Bulls, Cape, and Lighthouse islands, plays host to myriad species, including migratory shorebirds such as red knots and alligators

Walking the island paths with Crolley and Owen is like touring a museum with expert curators. “Look, there are two bald eagles,” Crolley points up to the top of a pine. “Just one of the 293 bird species on Bulls.” On the sandy path below, he notes deer hoof prints and the residual calligraphy from a snake. Owen offers tidbits about minks, otters, rabbits, and black fox squirrels. We spot a raccoon hunching along a creek bed. “Out here they’re tidal, not nocturnal,” she explains. Our stroll along the dike on the island’s northeast side is accompanied by percussive, heavy kerplunks as alligators loitering among the cattails take cover, heaving their massive, ancient selves into the water. A nearby ditch is filled with much cuter baby gators, barely a foot-long and maybe only a year old, Owen guesses.

The story for wildlife on Bulls Island three and half decades post-Hugo is generally a positive one. Populations have rebounded, and “the island’s dynamic edges—a term Mancke used to note the boundaries between ecosystems—remain incredibly diverse and dynamic,” says Crolley. In Bulls’ upland forests, you’ll find woodland birds, including blue jays, warblers, and finches, he says, and as a critical habitat for seabirds and some 100,000 migratory shorebirds, Bulls is unparalleled. It’s a prime resting and feeding spot for the threatened red knot before the intrepid birds begin their astounding direct flight to the remote upper reaches of the Arctic. This stretch of Cape Romain also hosts 15 percent of the US East Coast and Gulf Coast population of American oystercatchers (and 42 percent of the state’s) and 11 percent of short-billed dowitchers, according to the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network (WHSRN), which declared Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge a Site of International Importance in 1995.

“Because of its importance to the American oystercatcher and migratory birds as they cross the hemisphere, our WHSRN designation expanded again in 2018, almost doubling its original size,” says Felicia Sanders, coastal bird conservation project coordinator for the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. “As more people learn about these birds and their dependence on our coast, they take pride that birds stop here. We used to just be proud of our sea turtles, but that’s changing. We have so much wild space on the South Carolina coast,” she adds.

As the primary scientist monitoring shorebird populations along our coast, Sanders notes that while there has been a documented decline in American oystercatcher populations in recent years, it’s not necessarily attributed to storms. “There’s a chance Hugo did some good for a short while. A hurricane flattens the beaches, knocks down high dunes and trees, and cuts new inlets. It takes out predators like raccoons, and shorebirds love this,” she explains. “They love open sandy spaces, not trees. A Hugo-like storm resets that great shorebird habitat. But it’s very temporary,” she cautions. “Because we have developed the rest of the coast, which leaves no place for beaches and marshes to naturally migrate, once the outer beach and front beach [of barrier islands like Bulls] are knocked down, there’s no place for the birds to be.”

“It’s just a matter of can they keep up, given sea-level rise and loss of sediment in relation to higher, stronger tides. Without these islands, species like sea turtles and shore birds can’t survive.” —Sarah Dawsey, Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge manager

Owen offers us a lift, safari style, in the back of a Coastal Expeditions truck to glimpse Mills Road paralleling the front beach on Bulls’ south end. We bump along, ducking below overhanging oak and palmetto branches. The canopy here tunnels over us, thick and tangled and primordial. The gentle ridges of old dunes undulate along the road’s edge, sandy wrinkles of geologic time. “This is a last vestige of what the whole island looked like before Hugo,” she says, raising her voice above the loud buzz of insects’ ambient soundtrack. The otherworldly beauty, more than the heat, takes your breath away.

Bulls Island may be a wildlife refuge, but it’s also a refuge for the human spirit—a restless ribbon of resilience and hope, where red knots feast on baby horseshoe crabs and oystercatchers catch a meal and a break. The island is still in an active state of regrowth and rebound, even as threats mount. “Bulls Island and other barrier islands are very important protection for us in the event of hurricanes,” says Dawsey. Their natural ability to shift and move is key to their guardianship. “It’s just a matter of can they keep up, given sea-level rise and loss of sediment in relation to higher, stronger tides. Without these islands, species like sea turtles and shore birds can’t survive.” The Cape Romain barrier islands also protect the 27,000 acres of marsh behind them, “which is a critical nursery for all sorts of aquatic species,” she adds. “Without the islands, the marsh is going to go away.”

The lessons we can learn from Bulls Island are as countless as the island’s mosquitoes. As Mancke continually pointed out, nature is one big recycling program, and even a catastrophic Category 4 hurricane is simply part of that interconnected cycle. “When you try to touch one thing by itself, you find it hitched to everything in the universe,” he was fond of saying, quoting John Muir. While a barrier island is by definition an island, detached and standing alone, Bulls Island remains inherently “hitched” and connected to the well-being and protection of our mainland, our fisheries, and our bird life. “It’s a mystical landscape,” says Crolley of the island that withstood Hugo’s tempest to proclaim its enduring testament—the wisdom of the wild.

Photographs by Mike Habat; Allen Sharpe Photography; Bob Raynor/US Fish & Wildlife Service; Allen Sharpe Photography; courtesy of NOAA; photographs by Felicia Sanders/South Carolina Department of Natural Resources; Tricia Midgett/US Fish & Wildlife Service; Steve Hillebrand; C. Taylor Photography; Allen Sharpe Photography