Read up on kingpins, corruption, and infamous mobster Al Capone

There was a time in the history of our country, a 13-year period between 1920 and 1933, when a pesky inconvenience called Prohibition was made law. This was a nationwide ban on the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages—except for the religious wine served at communion. Across the land, citizens lawfully put away their bottles of aged Kentucky Bourbon and dutifully pulled out the teacups. People forgot their fondness for their afternoon gin and tonic and settled instead for tall glasses filled with sassafras and soda.

Well, some did. From time immemorial, Charlestonians have shown a propensity for the enjoyment of alcoholic beverages. What’s more, they have few compunctions when it comes to flaunting laws with which they disagree. Prohibition? A nuisance, no question about it, but did it stop drinking in this town? Not in the least. People not only continued to imbibe, but with a tradition dating to the days of the Confederate blockade runners, the Lowcountry became a hotbed for rum-running and the manufacture of a home-brewed corn whiskey called “moonshine.”

While backwoods bootleggers were active across the state during Prohibition, one place outshined them all. Hell Hole Swamp in Berkeley County became so famous for the corn liquor made in its hinterlands that it gained a national reputation. “Berkeley County is a festering sore in South Carolina,” ranted the state’s pious and fervently dry Governor John G. Richards in 1929. A rabid Prohibitionist, Richards had gained even less popularity two years prior when he resurrected a blue law dating from 1700 making selling gasoline and playing golf illegal on Sundays. Richards was so determined to wipe clean the stills of Hell Hole Swamp that in 1930, Charleston newsman Tom Waring Jr. wrote, “Hell Hole Swamp, exuding an aroma of spirituous liquors which reeked throughout the Southeast, was a stench in his nostrils.”

Despite Richards’ attempts to drain Hell Hole Swamp of its highly profitable bootlegging business—and the repeated raids by the state and federal revenue agents known as “Prohi” men—the illegal corn-liquor trade flourished. Mason jars filled with Hell Hole Swamp moonshine were shipped by the boxcar to Al Capone’s Chicago; lined the shelves of speakeasies in New York; and filled the teacups at blind tigers in Columbia, Savannah, and Atlanta. Closer to home, it kept the citizens of Charleston in the afternoon cocktails to which they were long accustomed. As one elder matriarch of Holy City society quipped, “Of course we continued to drink during Prohibition. I don’t know where Daddy bought the liquor. It was just delivered to the back porch every morning with the milk.”

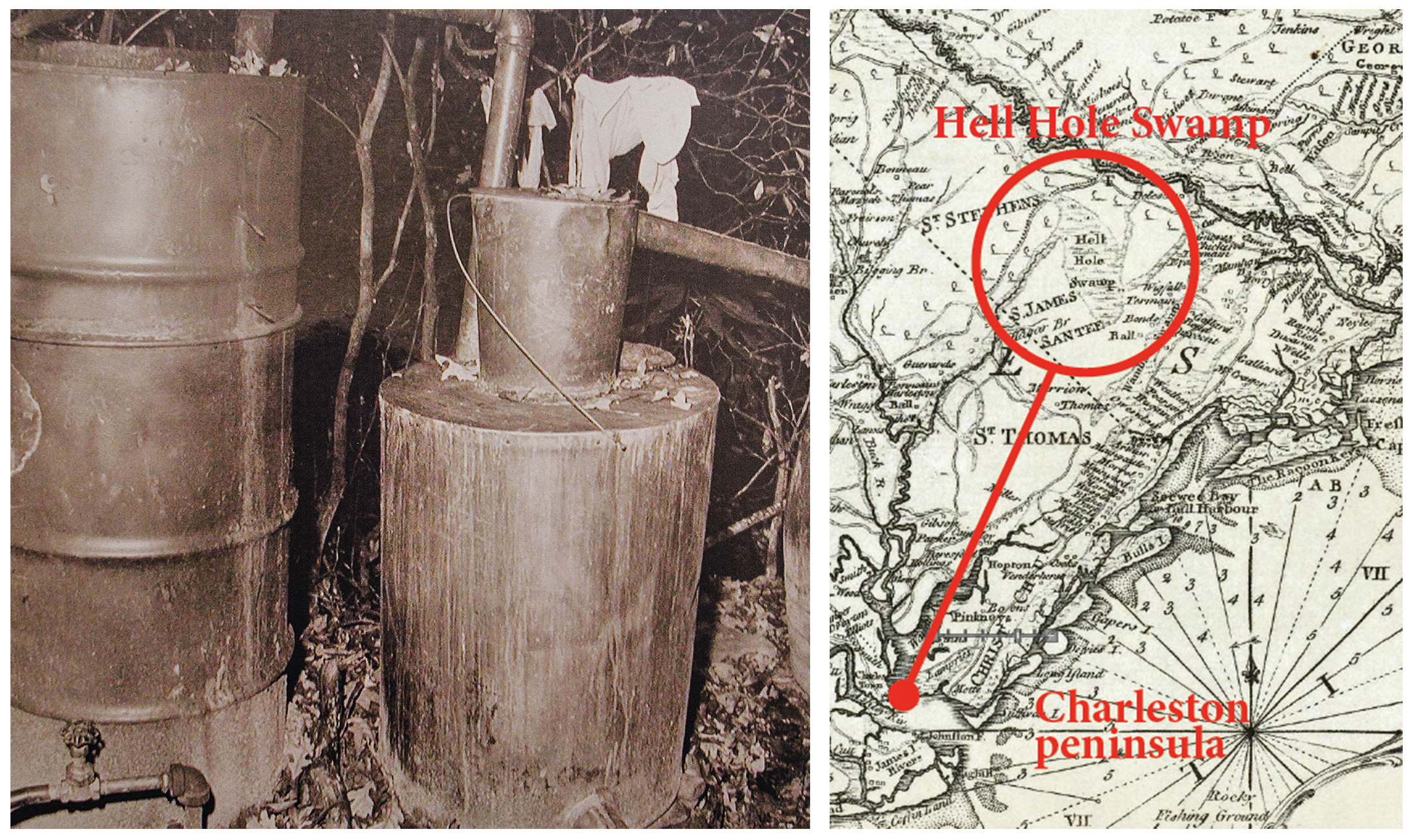

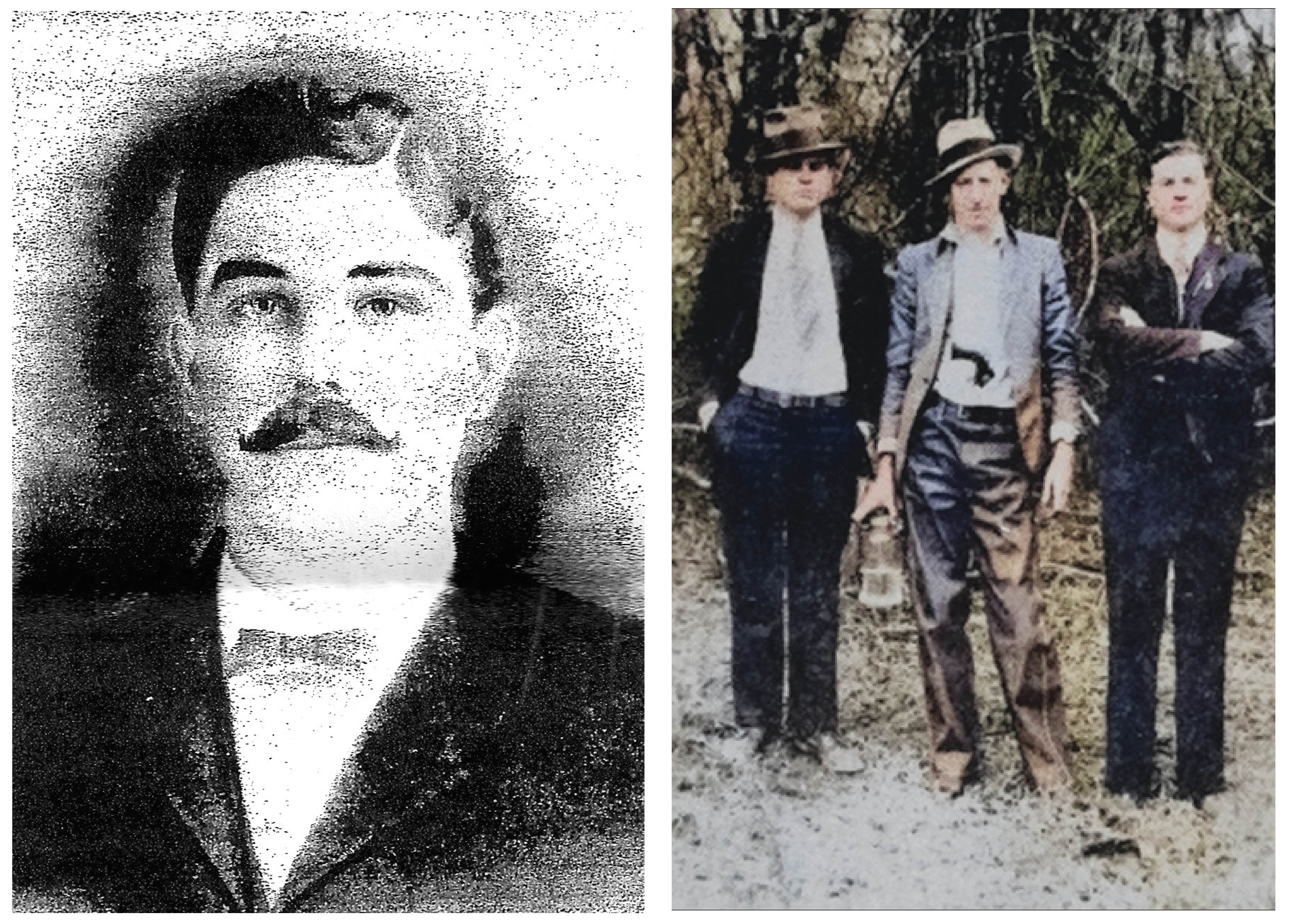

(Left) Examples of vintage stills in the Southeast; (Right) With its thick forests and unimproved roads, Hell Hole Swamp made an ideal location for illicit liquor production.

Hell Hole Swamp

While there are probably topographical maps showing distinct geographic boundaries for Hell Hole Swamp, the name generally refers to an area of swamplands and dense, piney woods that stretch from Jamestown on the Santee River to Moncks Corner on the Cooper River, and from Awendaw and Cainhoy upward to Huger, Cordesville, and St. Stephen.

From the beginning of colonial settlement, this misbegotten area has been called “Hell Hole;” the name shows up on maps that predate the Revolutionary War. In fact, General Francis Marion gained fame for the ease with which he and his partisan rangers eluded the British in Hell Hole’s murky recesses, earning the nickname, “Swamp Fox.”

Even today, Hell Hole Swamp is better left to the alligators, bears, bobcats, foxes, snakes, panthers, and other denizens that crawl, slither, and stalk its indefinite boundaries. Hell Hole is the rightful domain of the water moccasin and anvil-headed rattlesnake. Its air is choked with swarms of mosquitoes and biting deer flies. Entering the treacherous mires of this wild part of the Lowcountry is not for the fainthearted or inexperienced. If you don’t get lost, you will assuredly get bitten by something. With luck, the worst will be a rash of chigger bites.

There was a time that this region had a wealth and prosperity brought by the great rice plantations that once lined the rivers. Starting in the late 1600s, the French Huguenots were among the earliest to settle these lands, joined by colonists from the British Isles and the Caribbean. The swamps were tamed into rice fields, reaping profits that bought the planters town houses in Charleston and sent their sons to England for education and their daughters to finishing schools and on European tours.

The Civil War changed all that. By the 1920s, the plantations were in ruins and the rice fields had reverted back to swamps. Hell Hole had been left behind, forgotten. Those with better sense had long since fled to Charleston or Columbia, any place where a reasonable livelihood could be made. Those who remained were a hardy lot, but some had become almost as feral as the swamp. “People there became a hard, unkempt, and illiterate race, ignorant and superstitious, but with a pioneer’s jealous love of freedom,” wrote Waring. Far removed from their cultured antecedents, they had been changed by time, isolation, and a lack of education.

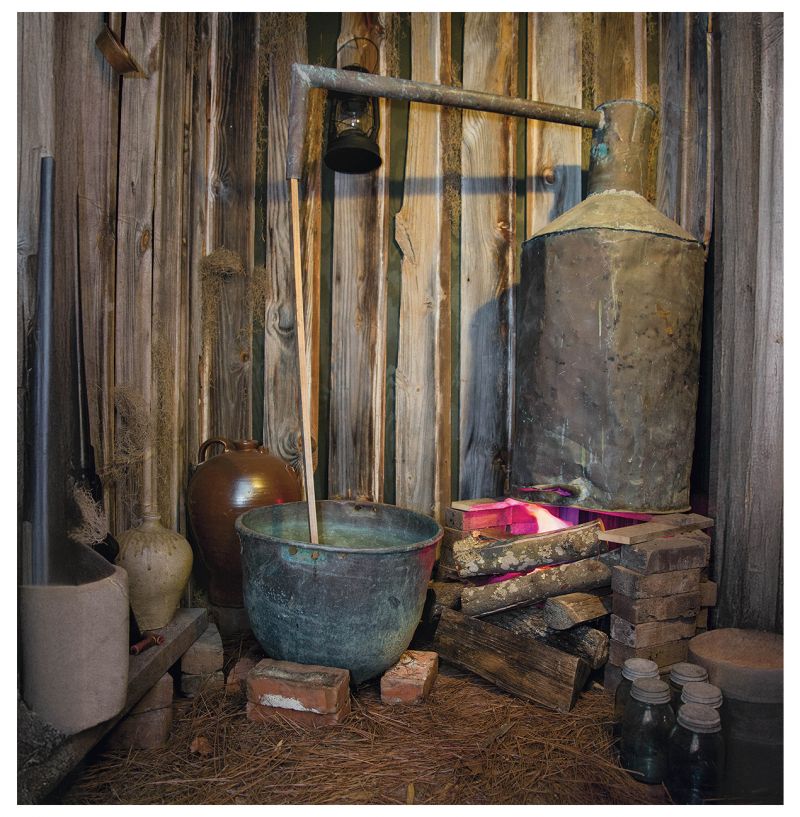

Hell Hole’s Prohibition-era inhabitants lived a hardscrabble existence in dogtrot cabins with tar-paper roofs and newspaper-covered interior walls. There was often an outhouse in the yard and a blue-tick hound asleep in the dirt under the sagging front porch. Behind the house, there was a garden where tomatoes, beans, and the essential stand of tall corn grew. And back yonder in the woods, hidden in the swamp, was the still.

Corn liquor had been made by the people of Hell Hole Swamp for ages. Most families had their own recipes, their own special products with distinct tastes. Prohibition made little difference to them. For that matter, sometimes the “law” was a brother-in-law or uncle who gladly turned a blind eye. Thus when people from Charleston came knocking at the door, looking for raw “still juice” to take home and age in charred kegs, they gladly made the sale.

As Prohibition dragged on, sales became more numerous. So did the number of stills. For years, moonshine had been a household commodity—now it was profitable. Rusty trucks and automobiles filled with brimming mason jars rattled down the dirt roads to all parts of the state. The whole region was getting happily drenched in Hell Hole corn whiskey.

Business was booming. “Stills sprang up like mushrooms,” wrote Waring. “Sandy farms which never had been productive were abandoned. It was much easier to run a still.” But Governor Richards had other plans for the residents of Hell Hole who were so blatantly ignoring the law. And, as in any bull market, competition became keen. Soon the fighting between rival families grew as hot as the boilers cooking the mash.

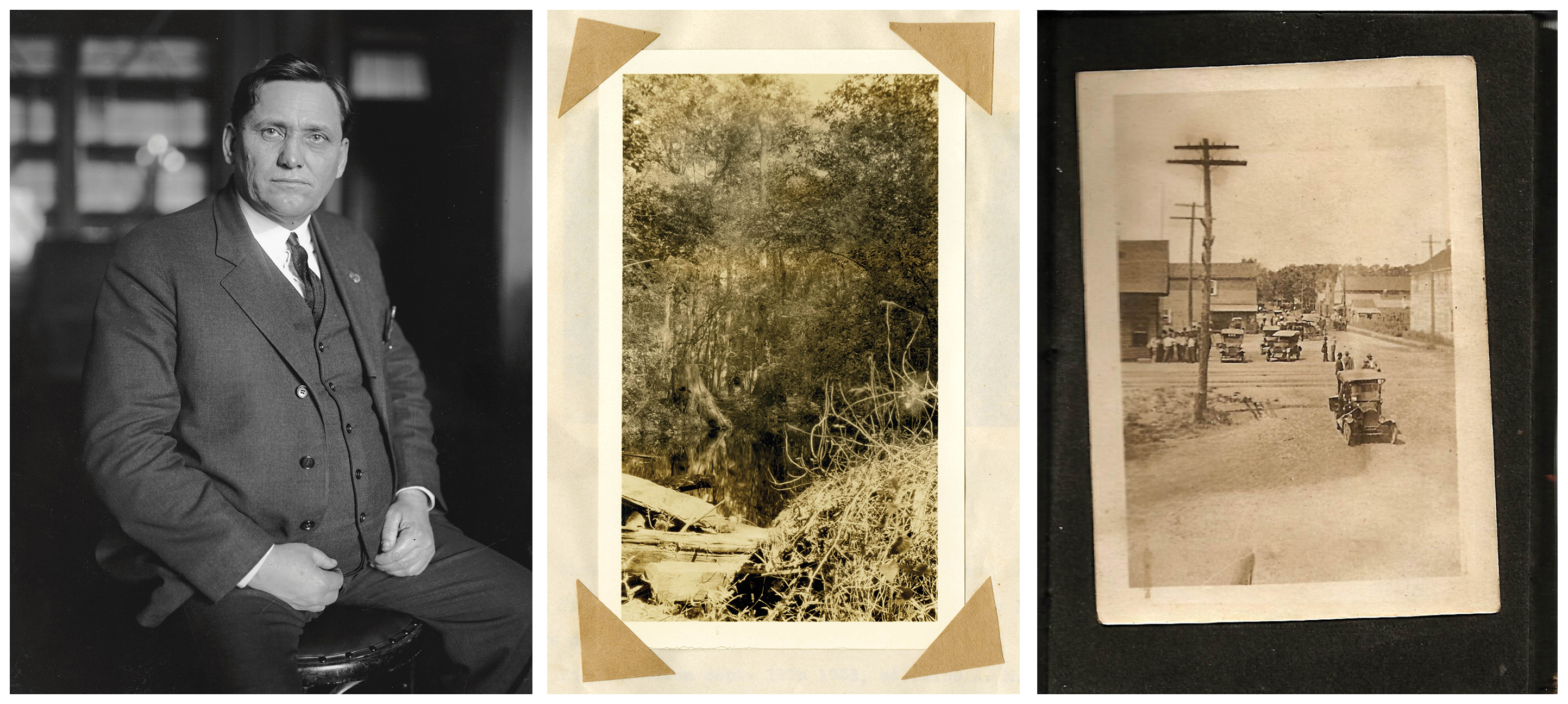

(Left to right) US Senator Smith Wildman Brookhart of Iowa, the namesake of the Brookhart Committee, which investigated discrepancies and corruption revealed in the Hell Hole raids; A view of a still site; a boiler would be set up in a remote area, preferably on a small stream since water was essential for production; A photograph of Moncks Corner on the day of the great shoot-out between rival bootlegging gangs, the McKnight organization and the Villeponteaux clan, in 1926.

Fox In The Henhouse

One of the enterprising magnates of the Hell Hole moonshine business was kingpin Glennie McKnight. He furnished the equipment, sugar, and cornmeal to the men who ran the stills and took care of distribution and marketing. At all steps of the process, “McKnight corn” was putting money into everybody’s pockets. Others within the McKnight organization were his brother, Sammie, and their friends, the Mitchums and Johnsons. Among McKnight’s rivals were the Ben Villeponteaux clan, which included his cronies, the Wrights and Andersons. The feud between the two groups turned violent.

On May 8, 1926, they came to blows on a highway near Moncks Corner in a gangland-style shootout. Glennie McKnight came out unhurt, but his brother, Sammie, was killed, as was Jervey Mitchum. Ben Villeponteaux was seriously wounded, as were Jeremiah Wright and James Anderson. Less than two weeks later, another ambush shooting near the little crossroads town of Huger killed LeGrand Cumbee and seriously wounded his father, the “king of Hell Hole Swamp,” Sabb Cumbee.

The gunfights in “bloody Berkeley” made national news, and the Federal government decided to take action. While there had been efforts by the state government to enforce Prohibition in Hell Hole Swamp, they had been half-hearted and largely ineffective. Agents would occasionally blunder onto a still and destroy it. Mostly, though, they got lost in the swamp’s wild morasses. The Feds realized they needed someone who knew the territory, a man familiar with the bootlegging families and the wilds of Hell Hole Swamp to lead the effort. They hired none other than the kingpin himself, Glennie McKnight.

Why McKnight became involved is probably still up for discussion. Some say he took the job to avoid a Federal indictment. Others claim he sought revenge for his brother’s murder. Almost all agree it provided him with a legal way to destroy rival stills. Whatever the reason, McKnight put on his badge and went to work.

On September 3, 1926, the Coast Guard cutter Yamacraw carrying 100 Federal agents entered Charleston Harbor. The following day, led by McKnight, they invaded Hell Hole Swamp. The raid took two days and resulted in the arrest of 33 men (including a sheriff and a deputy) and the destruction of 17 stills. Thousands of gallons of whiskey were poured onto the ground.

More raids followed during the year that McKnight worked for the Feds. On the local and state level, the raids were considered a success; however, the US Senate was not impressed. Moonshine was still gushing out of Hell Hole Swamp. As newsman Waring wrote, “The stream of white corn whiskey still flowed from that valley of a thousand smokes, where nearly every smoke marked a still.”

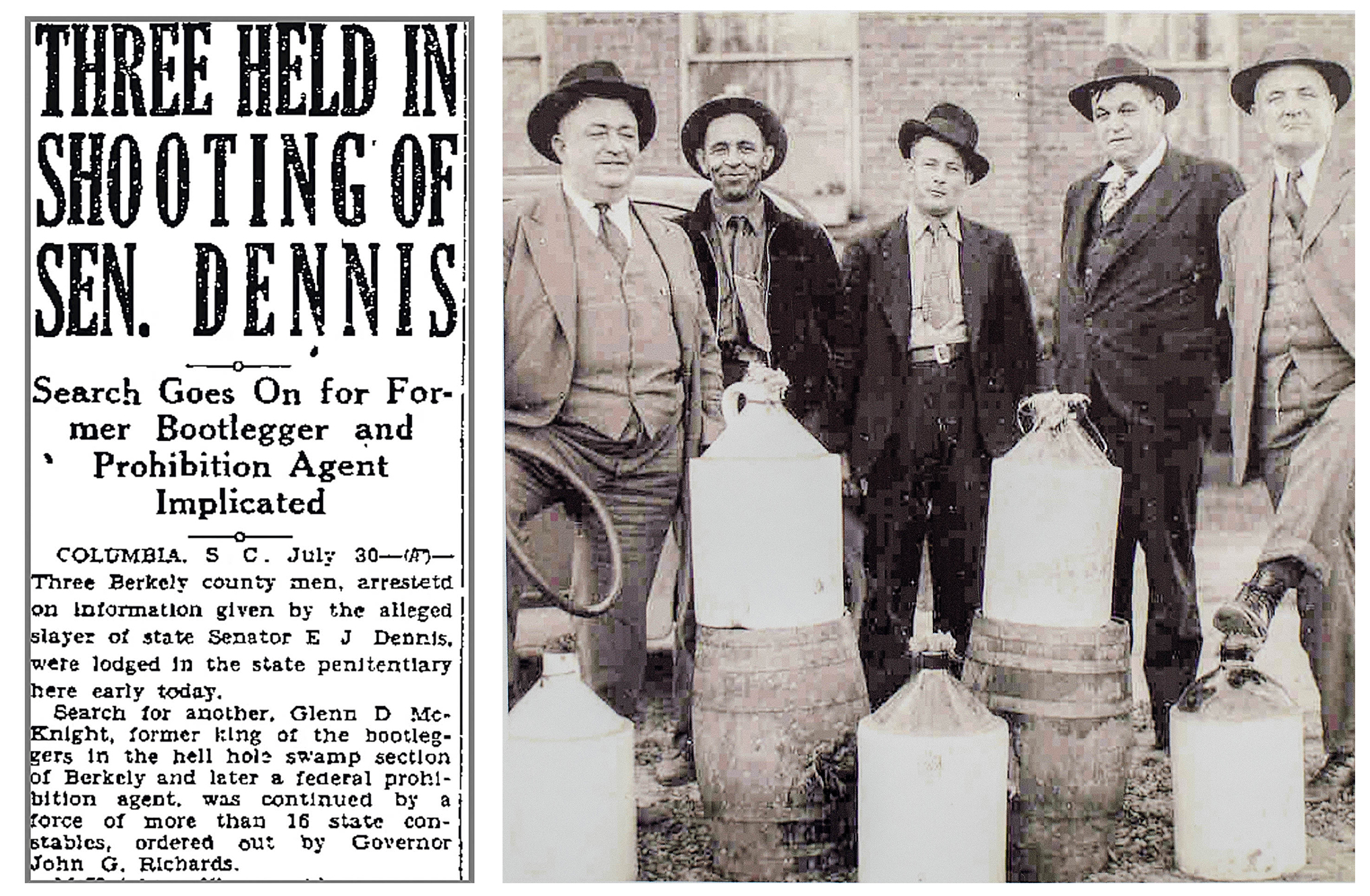

(Left to right) Headlines of the 1930 assassination of Senator Edward J. Dennis in Moncks Corner filled newspapers across the country; (right) Raids of stills took place throughout the state, with authorities taking possession of the liquor, as shown in this circa-1930s photograph taken in Pickens County.

Infighting & Politics

“Do you mean to say you hired the king of the bootleggers to be a Prohibition officer?” gasped Senator K. D. McKellar of Tennessee, a member of the US Senate’s Brookhart Committee, which was investigating the numerous discrepancies uncovered with the Hell Hole Swamp raids. The more the Senate probed into the Prohibition-ignoring moonshiners of Hell Hole, the more they became displeased.

“Bootlegging continues,” attested state constable J. L. Poppenheim. “McKnight may have cleaned up part of the county, but it didn’t help much.” Indeed, after McKnight turned in his badge, he went right back into the bootlegging business.

The findings of the Brookhart Committee’s investigations and later hearings in Columbia brought even greater gasps of astonishment and more than a few sniggers of amusement. It was becoming evident that law-enforcement officers, from sheriffs to deputies, had either been buying corn whiskey, selling it, or giving seized whiskey away to their friends. Even squeaky-clean Governor Richards became involved: His son-in-law had been found transporting whiskey across the state after leaving a deer hunt near Hell Hole Swamp; four bottles of Hell Hole liquor had been put in his car trunk by Berkeley County deputy sheriff W. E. Woodward.

Enraged, Governor Richards ordered Sheriff C. P. Ballentine to fire Woodward. When Ballentine refused, Richards ordered Ballentine removed from office. Ballentine, who was an elected official, appealed to the Supreme Court, saying the governor did not hold such executive privilege. Meanwhile, the governor also accused Ballentine and Woodward of not only selling seized liquor but imbibing it themselves. In the end, the Supreme Court decided with the governor. Ballentine was out.

Clouds were also beginning to gather around Berkeley County State Senator Edward J. Dennis. The Feds, still on the hunt, called in Ballentine and Woodward to testify about what was really going on in Berkeley County. The real people in the whiskey business, they said, were none other than Senator Dennis and the state constables (purportedly members of the Anderson-Villeponteaux gang) whom Dennis had personally asked the governor to appoint as Prohibition agents.

Ballentine’s and Woodward’s testimonies were damning. They explained how Dennis and his cronies were getting rich through a foolproof system that operated on many levels. It worked like this: The constables would arrest a moonshiner and seize his whiskey. They then sold the whiskey to their own bootleggers. Senator Dennis, who was a lawyer, made his money through attorney’s fees when he represented the moonshiners who’d been caught. Given his influence, Dennis could arrange to have the cases dropped, but only for a “consideration.” These fees, said Ballentine and Woodward, amounted to nothing short of paying tribute to the “king of the bootleggers.”

A special investigator and prosecuting attorney were appointed. Indictments were issued against Senator Dennis and the constables. The trial was held in Charleston, with a long line of moonshiners parading across the witness stand, most of whom substantiated the charges.

It was all nonsense, testified the senator. Who could believe bootleggers, anyway? With a brilliant defense that included testimonies from congressmen and some of the foremost lawyers of the state, the jury eventually brought in a verdict of acquittal. Throughout it all, corn whiskey poured from the stills in Hell Hole Swamp. Raids continued but with the same, ineffectual results. And the bitterness between rivals festered.

This came to another bloody climax when, on the morning of July 24, 1930, as Senator Dennis was walking to his office in Moncks Corner, 30-year-old W. L. “Sporty” Thornley placed a shotgun on the radiator of his car and fired a load of buckshot into the senator’s brain. He died the following day.

Thornley was arrested, as was his brother, Curtis, and Fred Artis, the bodyguard of Glennie McKnight. Sporty, who was described in newspaper articles as a “tubercular, disabled, World War I veteran” and town loafer with the “intelligence of a boy of 12,” later testified that it was Glennie McKnight who had furnished him with the gun. For shooting Dennis, McKnight had promised Sporty cash, protection, and a house for his family. McKnight was also arrested. Yet in the end, only Sporty was convicted and given a life sentence.

Moonshining continued and McKnight and his rivals continued to profit from the stills of Hell Hole Swamp. McKnight, himself, barely avoided death. In May 1930, he was wounded by a hail of gunshot as he was leaving his home. In late April 1932, McKnight was ambushed again, his car riddled with bullets as he pulled away from a store in Huger.

Prohibition was finally repealed in 1933. Now that liquor was legal, the flow of big money into Hell Hole Swamp ceased. As for the backwoods stills? The Hell Hole residents continued to enjoy, and sell, the white corn liquor they concocted in the swamp’s murky interiors. In all likelihood, they still do.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

(Left) Sabb Canty Cumbee, aka the “king of Hell Hole Swamp,” was the leader of one of the Berkeley County moonshine gangs. In 1926, he was seriously wounded in an ambush by a rival gang that left his son LeGrand dead; (Left to right) Al Capone, David Shuler, and an unknown man in Hell Hole Swamp; “Mr. Shuler ran a mercantile store in Jamestown. This photo hung in his store until it closed,” says Jamestown resident Douglas Guerry.

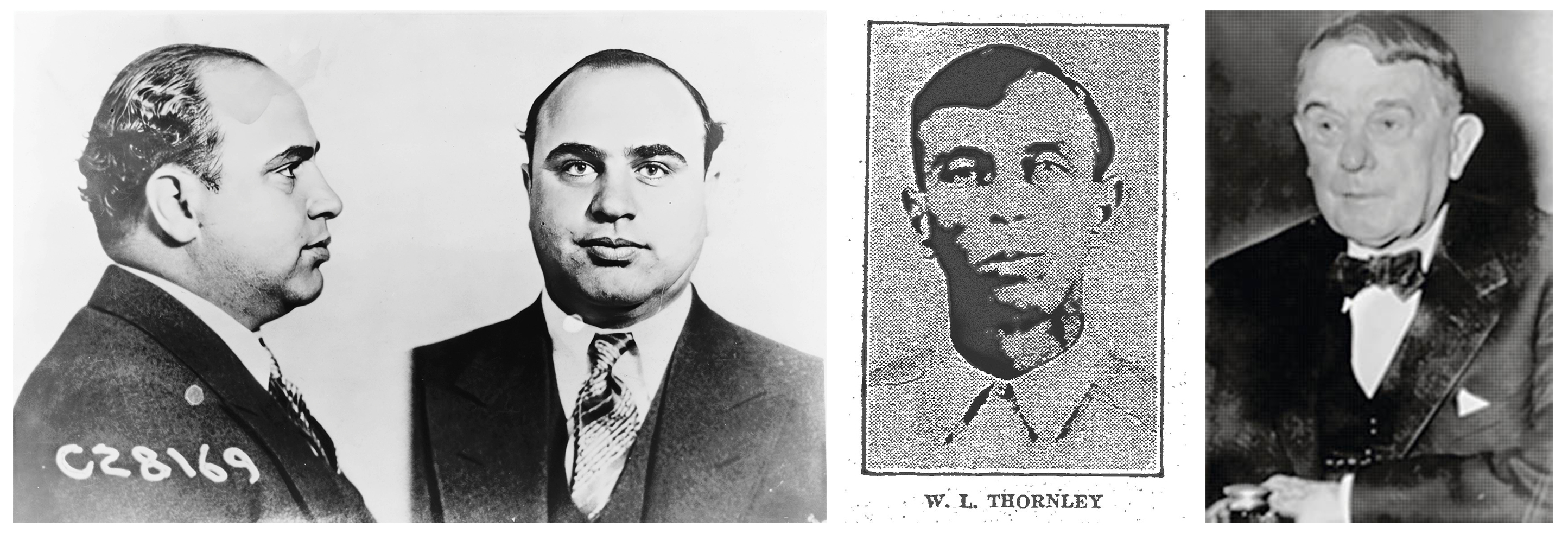

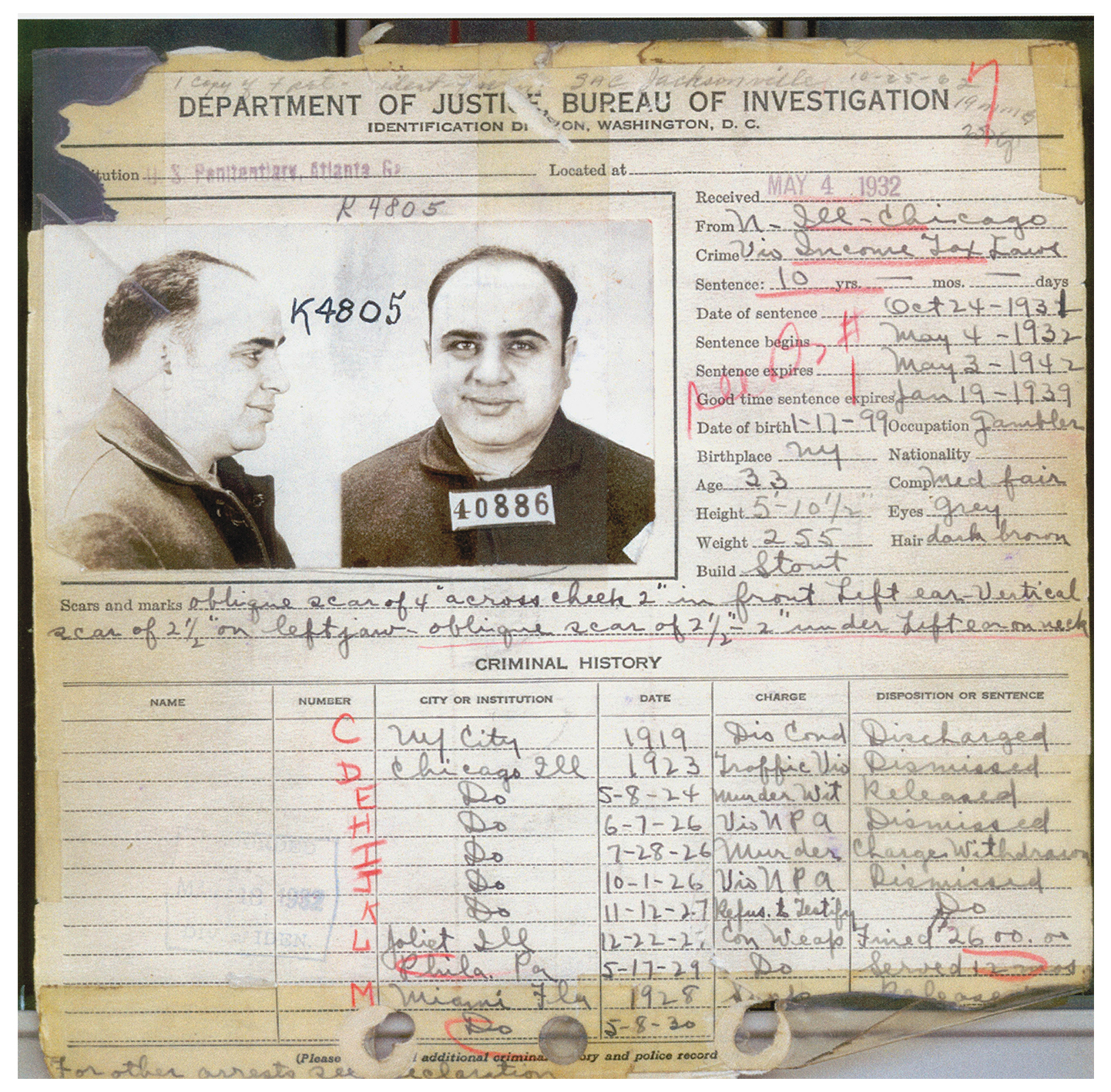

(Left) Infamous Chicago mobster Al Capone is said to have conducted business with Hell Hole bootleggers, allegedly meeting them at a roadhouse in St. Stephen a number of times; (Right) Part of the McKnight gang, 30-year-old “Sporty” Thornley (left) was arrested and convicted of the assassination of State Senator Edward J. Dennis in July 1930. Senator K.D. McKellar (right) of the Brookhart Committee, which investigated the Hell Hole raids.

Al Capone

Hell Hole Swamp was purportedly one of the biggest suppliers of illegal liquor to Chicago during Prohibition. Stories abound about how racketeer Al Capone would arrive in a fancy limo with his henchmen and wads of money “to take care of business.” Moonshine kingpins Glennie McKnight and Jerry “Foxy” Christian would buy all the corn whiskey they could from local bootleggers and ship it to Chicago in railroad boxcars. One yarn tells of the time Capone didn’t pay for a shipment sent up by McKnight. When McKnight refused to send more, Capone supposedly sent six Cadillacs filled with his toughest hoods down to teach the Hell Hole moonshiners a lesson. McKnight’s boys led the gangsters in their leather shoes and fancy suits into the swamp and left them there after taking their money and their cars.

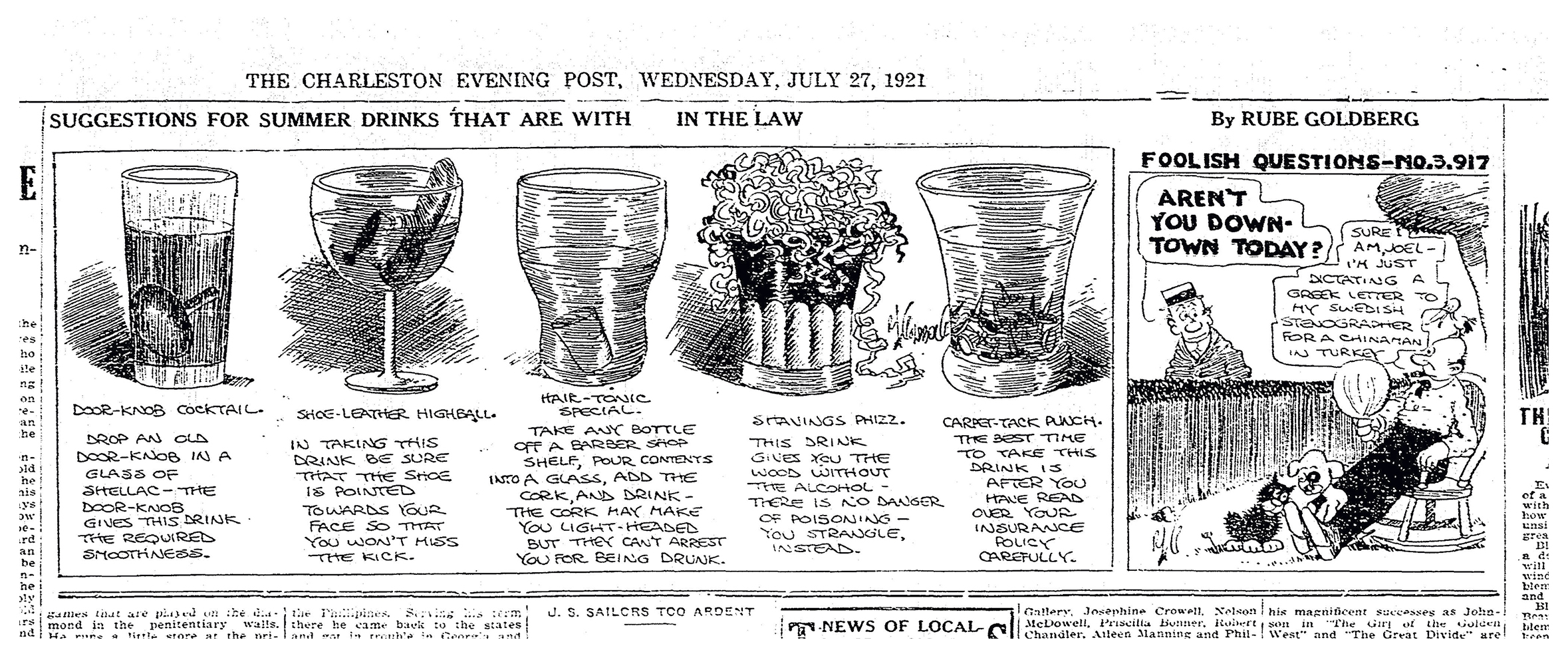

More than a year into Prohibition, readers of The Charleston Evening Post no doubt appreciated cartoonist Rube Goldberg’s “mocktail” commentary on legal drinks.

Moonshining: A Glossary

MOONSHINE: The word is an adaptation of the word “moonrakers,” an archaic term for early English smugglers; of course, it was also inspired by the fact that in order to avoid discovery, most distillation was done at night by the light of the moon.

BOOTLEGGER: Some state that the term hearkens back to the age of sail and the smugglers’ custom of hiding packages of valuables in their large sea-boots to avoid detection. Others attribute it to the Civil War, when soldiers would sneak liquor into army camps by concealing pint bottles in their boots or beneath their trouser legs.

SPEAKEASY: The name given to saloons during Prohibition (they were also known as “speak softly shops”) arose from the practice of speaking quietly in public about a place that sold illegal alcoholic beverages.

BLIND TIGER: Also called a “blind pig,” it was the term for establishments that sold alcohol without a license. To circumvent the law, they would charge customers to see an attraction, such as an animal, and then serve a “complimentary” alcoholic beverage.

RUM-RUNNING: The many inlets and rivers on the Lowcountry coast made running liquor in from Canada, Bermuda, and the Caribbean a profitable business. Charleston newspapers often reported the discovery of “red liquor,” wine, and various imported whiskeys that “exchanged hands” in Berkeley County and Charleston.

Others simply smuggled in labels. Under the headline of “Foreign Labels on Moonshine,” one newspaper report told of agents who raided an abandoned house near Moncks Corner and found “several hundred empty bottles bearing Canadian Club and other labels, a considerable quantity of wrapping paper with similar designs, a supply of corks, loose labels, sealing wax, mucilage, caps, seals, and other supplies, together with several hundred empty fruit jars whose odor indicated that ordinary moonshine had recently been poured from them.”

From the archives: This feature first appeared in our December 2015 issue.

Images by (display) Ruta Elvikyte & (jug) Melinda Smith Monk/shutterstock.ai; courtesy of (Richards) Library of Congress, (Cumbee) findagrave.com, & (bootleggers) Jean Guerry; courtesy of (stills-2) Jerry Alexander, (maps-2) the David Rumsey map collection, (capone) Federal Bureau of Investigation, (thornley) newspapers.com, & (Mckellar) US Senate Historical Office; courtesy of (brookhart) Library of Congress/National; photo company collection & (still site) South Carolina Historical Society; courtesy of (street) Jean Guerry & (capone) Federal Bureau of Investigation & courtesy of Jerry Alexander