The couple left an indelible mark on Charleston culture, paving the way for modern art in the Lowcountry

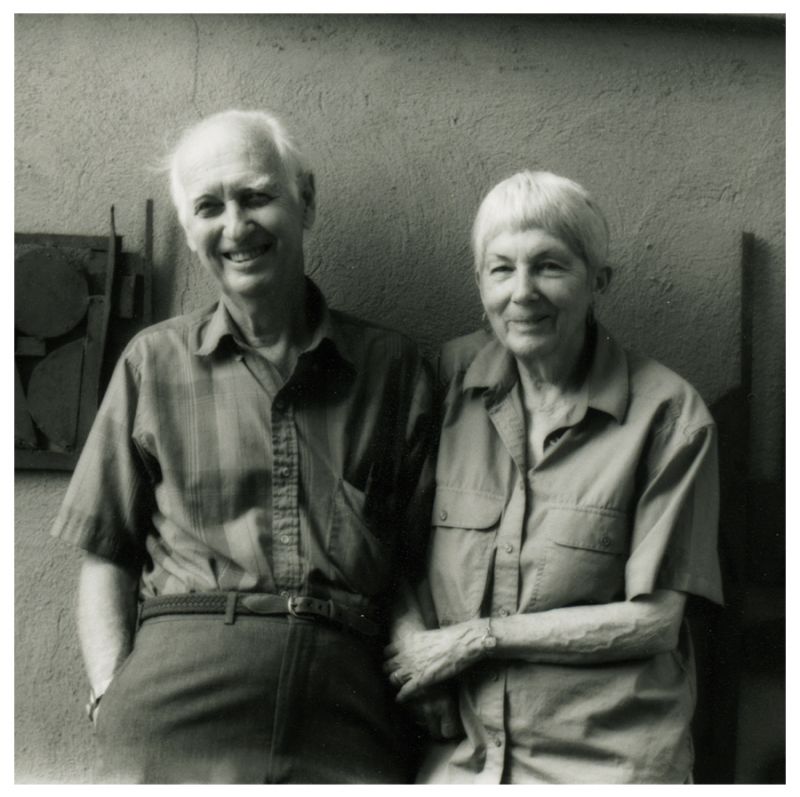

Like Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner, William Halsey and Corrie McCallum (pictured above left, right) fell in love with each other as they fell in love with art. Although they struggled with the demands of separate identities and careers and felt the stresses of family and finances, these creative souls forged a remarkable partnership built on the beauty they saw in shapes and colors. They embodied a spirit of bold experimentation in modern art that lives on today in studios and galleries throughout the Holy City and the South.

Everyone who knew the couple thought of them, at some point, as one person, and always they seemed a little that way. Yet William Halsey and Corrie McCallum came from vastly different backgrounds and expressed themselves artistically through vastly different media. Although both were native South Carolinians, McCallum, born in 1914, hailed from Sumter, where there was little cultural nourishment to feed her passion for art. Halsey, on the other hand, had been born in Charleston in 1915, coming of age during the city’s brightest moment in the national cultural spotlight—that period between the two world wars known as the Charleston Renaissance.

In 1932, the unlikely pair wound up studying art at the University of South Carolina. Halsey had already been exposed to a wide range of painting and drawing. At age 13, he was taking drawing lessons from Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, one of Charleston’s most famous etchers and printmakers. Later, in high school, he studied with Edward “Ned” Jennings, an eccentric whose modernist paintings—the only ones like them in the city—drew on ancient Assyrian and Babylonian mythology for their imagery.

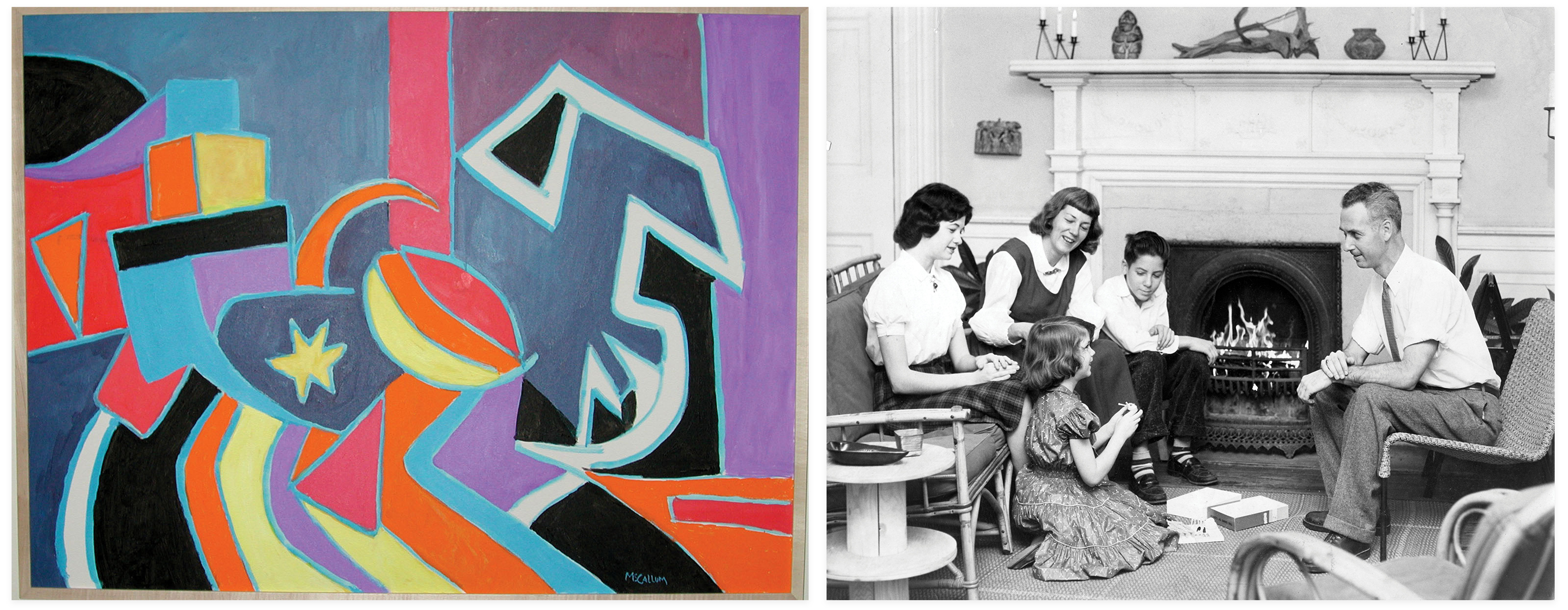

(Left) Red Square (collage and oil on Masonite, 46 x 48 inches, 1997) by William Halsey; (right) West End of George Street (casein on paper, 23 x 15 3/4 inches, 1941) by Corrie McCallum; she was often drawn to the less “attractive” parts of Charleston, as she felt the buildings conveyed complex emotions.

The university turned out to be a disappointment for Halsey. He felt that the rather conservative department (which did not, for example, allow nude modeling) didn’t pose enough of a challenge. By contrast, the program was a great leap forward for McCallum, as the only instruction she had received were rudimentary drawing lessons from a Sumter art teacher, who gave them in exchange for modeling.

After two years, Halsey quit USC and returned to Charleston, looking for a way to fulfill his creative urge. He missed McCallum, who remained in Columbia, terribly. She had been the one person, he felt, in the whole of South Carolina, with whom he could seriously discuss art. McCallum excelled in her studies. She had developed such precision and accuracy in her drawing that for a while she thought about becoming a medical illustrator. Halsey, the less strident and more contemplative of the two, wasn’t really sure what he was after, but like a child who gets a chemistry set for Christmas, he luxuriated in the pleasure of trying out new forms. He wasn’t interested in the Charleston “picturesque” school of pretty landscapes, even though his mentor Verner urged him to stay and “work out his salvation here.” He knew he had to go elsewhere. “I want to see what’s going on,” he told Jennings’s mentor Laura Bragg, “get a thorough foundation, and then… work out my own method for myself. Whether I’m a modernist, nonobjective, or realist, I want to say what I’ve got to say in my own way.”

After considering Yale University, among other places, Halsey enrolled at the School of the Museum of Fine Art (MFA) in Boston. Arriving in the fall of 1935, he immediately began to second-guess his choice; competing with students who were much younger and better trained than he was, Halsey felt terribly self-conscious and, at times, inadequate. He was a quick study, however, and soon made up for any lost ground.

The profound bond he had formed with McCallum also helped him find his footing in Boston. Although they were physically separated, in mind and spirit, they felt like they had never left each other’s side. McCallum finished her program in 1935 and then took a one-year post directing a gallery space for a Works Progress Administration (WPA) program in Columbia, the start of a career in arts education that would continue for most of her life. Casting about for her next move, she decided to follow Halsey to Boston, where she too took classes at the MFA school and did administrative work for the museum.

They decided to marry and, because of objections by both families, held the ceremony in Boston on June 5, 1939. McCallum chose to keep her maiden name—not exactly a revolutionary act but certainly not the norm at that time—as a gesture of artistic identity. As she explained later, “I did not want to get mixed up with who was what. I said to William one day, ‘That’s your painting. It’s nice, but that’s not me.’” This bold independence would be a characteristic trait throughout her career, as she would always define her own territory as an artist.

The artists in their Fulton Street studio, circa 1971; when they first met at the University of South Carolina, Halsey felt that McCallum was the only person with whom he could seriously discuss art.

Through his studies at the MFA, Halsey became drawn more and more to the abstract, to the expression of mood and movement through geometry and color. An unexpected opportunity came in 1939 when he won a travel fellowship to further his studies in Europe. Halsey and McCallum were all set to go, but their plans abruptly changed when Hitler invaded Poland that September. With Europe suddenly off limits, they traveled instead to Mexico.

They settled in the Villa Obregon section of Mexico City, setting up house in a ramshackle cottage at 162 Calle del Fresno. Nearby was the Academy San Carlos, where the famed muralist Diego Rivera taught, his rounded, saturnine images of the peasant classes known the world over. Although they admired the Mexican artist’s socially conscious paintings, Rivera never really influenced the couple’s work. Mostly they just absorbed the environment, attuning themselves to the imagery of the country. The textures of dusty villages and remote cities inspired Halsey in particular, and while there he began to hone his practice of expressive distortion, as well as his habit of layering a canvas, board, or other surface with applications of paint, cloth, ground-up pebbles, and other materials to create different levels of density.

It was in Mexico that McCallum gave birth to the couple’s first child, Paige, in 1940. McCallum delighted in motherhood but at the same time missed painting. She was amused to turn on the radio one day and hear Eleanor Roosevelt giving a speech about women having been freed from housework and the full care of children and now having time for other pursuits. “What women?” McCallum wrote home to her mother. Still, she managed at least two or three hours of work a day and pronounced herself “happy enough.”

When their money ran out in March 1941, the couple returned to Charleston and moved in with Halsey’s sizable family at 51 George Street, which was home to four generations. Fortunately for McCallum, the house had 14 rooms, so it swallowed them up “very nicely,” but there was friction between Halsey’s mother, who doted on him ceaselessly as the baby of the family, and McCallum, who unconventionally refused to answer to the name “Mrs. Halsey.”

Still, she was determined to share her time between her family and her art. Many of her works from this period are casein on paper streetscapes and views of houses with quirky angles and threatening skies, like the backyard in Charleston III. McCallum took in these views on her many walks around the city, pushing Paige in the stroller. She found herself drawn to the less attractive parts of the old town, the tenements and alleyways, because she felt that the buildings conveyed complex emotions. In works like West End of George Street, for example, and Charleston Houses, East Side, individual buildings—irregular, sloping, and some even tottering on the verge of imminent collapse—communicated moods to her; that building, she would think, is “happy,” or “sad,” or “laughing.”

(Left) Ringside #4 (acrylic on canvas, 30 X 40 inches) by Corrie McCallum; (right) The family, circa 1956: Paige, Corrie, Louise (on the floor), David, and William; McCallum was quoted as saying: “I’ve always felt that if you are a woman, it’s important, if possible, to experience all aspects of what that means, particularly our unique bond with children.”

Their family continued to grow—a second child, David, was born in May 1944—and Halsey was beginning to attract notice as a painter. His first professional exhibition, much praised by the Southeastern press, had taken place in 1940 at the Gibbes and soon after traveled to several museums in Virginia. In the meantime, their third child, Louise, was born in 1949, and McCallum poured her energy into her children. She regarded raising them as a different sort of creative endeavor, one she knew was her experience alone, another way of staking out independent territory. She later noted, “I’ve always felt that if you are a woman it’s important, if possible, to experience all aspects of what that means, particularly our unique bond with children. Men don’t have that closeness; no matter how nice and kind and good they are, they have a different relationship with children.”

Halsey, at this time, entered his most successful period. He had been discovered by Bertha Schaeffer, an interior designer in New York whose gallery showcased “home art,” paintings and other pieces that could be bought at reasonable prices and exhibited, so to speak, in private residences. Halsey took part in two group exhibits—“Fact and Fantasy” (1948) and “The Modern House Comes Alive” (1949)—in very good company. Marsden Hartley, Ben-Zion, Will Barnet, and several others of the abstract expressionist school were represented in these shows, which later traveled to the Met, the Whitney Museum, and the Art Institute of Chicago. By 1955, Halsey would have one of his paintings adorn a poster announcing the International Watercolor Society show at the Art Institute of Chicago, alongside a similar poster depicting a Picasso canvas.

Halsey was taking his place firmly alongside the second generation of post-Impressionists. While his work from this period on to the end of his life shares some surface similarities with the most famous of the New York School of abstractionists—Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, for example—Halsey appeared on the scene sometime after that group had already banded together and closed themselves off, to drink, declaim, and debate at such now-infamous spots as the Cedar Street Tavern in Greenwich Village and to exhibit at Peggy Guggenheim’s fabled Art of This Century Gallery.

Like Pollock, Halsey experimented with dripping and splattering paint, employing the methods of action painting to create background compositions, such as the bold, large-scale brushwork and expressive gestures in much abstract expressionism that sought to capture the act of painting itself. But he was also straining to perfect new forms, responding to Rothko’s soft, undulating color studies and Pollock’s whimsical brush strokes.

Night Houses, one of his most famous paintings from the 1950s, is a semiabstract work that blends the subtlest of color relationships and is similar to Back Street Charleston, which juxtaposes buildings and vegetation, sharply angled trees, overlapping rooftops, and a local church steeple to create a crisp, deftly balanced design. These works also convey effects that are almost poetic, like the suggestive moonglow on building facades.

However, Halsey also wanted to create his own vision, his own style. To him, the New York art community seemed self-absorbed, even narcissistic, and he later spoke of this period with some sense of disenchantment: “I was down. I got thrown off base because I was too impressionable. I started looking around, and everybody was doing…abstract expressionist paintings, and I had to try to be with it.”

He also felt strongly that intelligent art needed to be seen in other parts of the country. He later wrote, “There were too many artists in a few areas and too few artists in small cities and towns, and I felt I could be vastly more useful in my native state than any place else. If there was a more general distribution of creative artists working in smaller communities, there would be a wider interest in and understanding of contemporary art in this country.”

(Left) Old Man (oil on Masonite, 48 1/8 x 48 1/8 inches, 1972) by William Halsey; to get the texture for the painting, he mixed marble dust with the paint for a grainy finish; (right) Squared (oil on monotype paper, 26 3/4 x 31 3/4 inches, circa 1998) by Corrie McCallum.

In the 1960s, Halsey re-rooted himself in Charleston, where he lived until his death in 1999. For many years, he was associated with the Gibbes Museum of Art, where he taught, planned exhibitions, oversaw installations, wrote letters, answered telephones, and often, if no one else was available, mopped the floors. At the same time, McCallum became the curator of art education there and, as she had with the WPA, continued her work of exposing schoolchildren to art. Later, they both took teaching posts at the College of Charleston, where McCallum founded the printmaking department and Halsey—the first person to teach a studio art class at the college—was often referred to as the “Dean of Abstract Art in South Carolina,” a moniker he likened to being “the brightest orchid in Iceland.” Upon his retirement from teaching in 1984, the college named the art gallery at the School of the Arts after him.

The pair cut a curious figure in conservative Charleston. They were both artists, but they had no formal gallery, per se. In town, they were called teachers, but the rest of the world knew them as painters. Halsey wanted people to like what he did, “to have a public,” but he also relished estrangement. McCallum fulfilled the duties of a conventional wife—taking care of children, shopping, and doing household chores—while at the same time being a most unconventional artist: In 1968, she fulfilled a lifelong dream of traveling around the world by herself, and some of her most complex and outre works from this period—like the dark, somewhat dissembling woodcut Gates of Meknes—derive from her travels in India, Bali, Iran, and Iraq.

As their children grew and the couple gave over more and more of themselves to art, an interesting relationship developed between them. Halsey was always the artistic pathfinder, and McCallum pursued media that her husband wasn’t interested in: woodcuts, linoleum cuts, lithography, and other forms of printmaking. She also used the colors that he eschewed. When they moved into their studio space at 20 Fulton Street, Halsey had an addition built onto the back of the structure where he set up shop. It was an expansive, airy space with tall ceilings and abundant natural light, while McCallum took a much smaller, quite cramped room upstairs for her studio.

Halsey’s most treasured works became those with his trademark uses of the broken and worn materials that he folded into his art—painting cloths, denim, pebbles, and marble dust. In works like Red Square, the textures and colors of the shapes seem conflated with Charleston streetscapes. The experience of growing up in a city impoverished and neglected, surrounded by “flaking plaster, mortarless brick walls, old tiles, and rotting wood,” never left him. The textural layers of his work are so prominent that some of his paintings almost become a palimpsest of the city—fragments that evoke ruins, bits and pieces of a civilization long decayed.

McCallum’s late work, in contrast, delights in smooth, uninterrupted movement—it is spatial rather than directly visual—and one gets the feeling that she achieved her most sublime moment in the “WOW” series (a title that appropriately enough came from the usual response when visitors walked in the studio) that she worked on from 1999 until she had to give up painting, due to illness and age, at the end of 2003.

Halsey died on February 14, 1999 at age 84—a passing that occasioned a flurry of editorials, memorials, and commemorations. McCallum was forced to retire when vision problems, memory loss, and other ailments associated with Parkinson’s disease made working too difficult. She too had a wealth of praise poured on her work in essays and tributes, and in 2003 received the state’s venerable Elizabeth O’Neill Verner Award (now Governor’s Award for the Arts) for lifetime achievement. (Halsey earned the same honor posthumously in 1999.)

McCallum passed away 10 years after her beloved husband—and both of their works are in museum and private collections across the country and represented by Ann Long Fine Art and the George Gallery. Halsey and McCallum changed art in Charleston—and much of the South—by helping pave the way for modernism and validating the beauty of color, space, and shape in a picturesque place where change was once hard to come by.

McCallum and Halsey gave much of themselves to art education, including roles at the Gibbes Museum of Art. Eventually, both took teaching posts at the College of Charleston, where she established the printmaking department and he earned the informal title, “Dean of Abstract Art in South Carolina.” The college’s Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art was named in his honor.

Find Halsey and McCallum’s works on display around town this season

The George Gallery:

“Other Worlds”

May 22-June 8

This solo exhibit of Corrie McCallum’s paintings and prints, opens on Wednesday, May 22 with a reception from 6 to 8 p.m. The gallery also represents and shows a number of works by William Halsey.

54 Broad St. (843) 579-7328, georgegalleryart.com

The Gibbes Museum of Art:

“Artist Spotlight Series: William Halsey & Merton Simpson”

Through August 18

A selection of works by Charleston-born abstract expressionists William Halsey and Merton Simpson (1928-2013) from the museum’s permanent collection will be on display.

135 Meeting St. $12-$6. (843) 722-2706, gibbesmuseum.org

The Dewberry:

Ongoing

See four large works by Halsey in the lobby of this downtown hotel.

334 Meeting St. (843) 558-8000, thedewberrycharleston.com

Web extra!

Watch this video from the Gibbes Museum’s “Make Like an Artist” series that deconstructs Halsey’s creative process.