Get a refresher on the city’s integral role in preparation for our country’s 250th anniversary

Vestiges of the American Revolution are everywhere in Charleston, from the grand residences of avid patriots such as Miles Brewton and Thomas Heyward Jr. to sites like Fort Johnson, Fort Moultrie, and the Old Exchange. Artifacts abound in the city’s many museums, their archives filled with the stories of the people who rallied behind the cause of liberty, as well as those who didn’t.

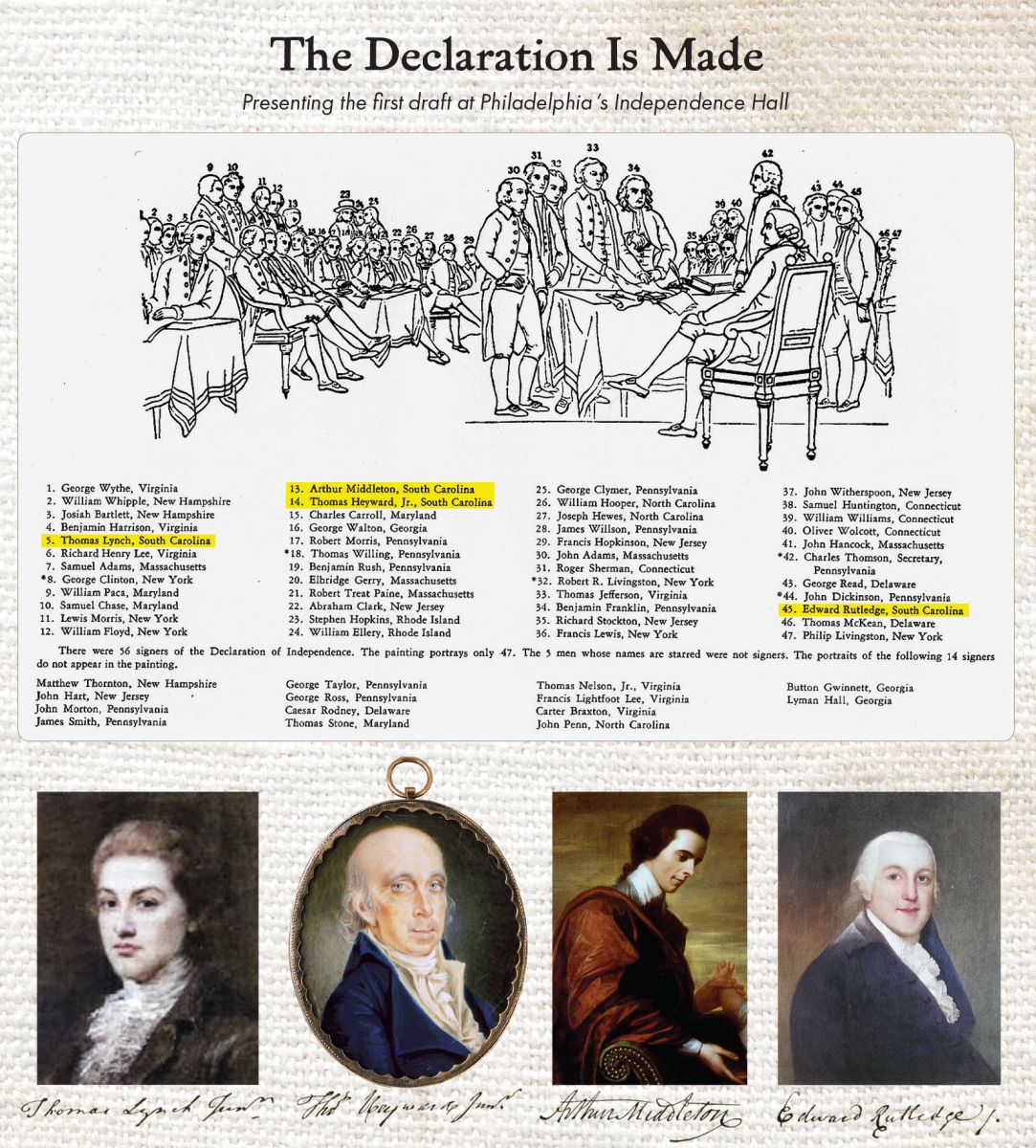

This year, throughout the nation, celebrations, events, and tributes will be held to commemorate the 250 anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the birth of the United States. In Charleston, in particular, the anniversary bears special significance. Four South Carolinians—Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr., Arthur Middleton, and Edward Rutledge—affixed their names to the Declaration. And it was here, more than any other Southern city, that the lines between liberty and tyranny were drawn. “It was the most important city in the South,” says Carl Borick, director of The Charleston Museum, the nation’s oldest, founded in 1773. “It was the biggest port in the South and the wealthiest city in colonial America.”

While the traditional narrative of the War for Independence focuses on the North in cities like Boston and Philadelphia, it was in South Carolina that independence was won. There were more than 400 battles, skirmishes, and significant events across the Palmetto State alone, often pitting neighbor against neighbor. “In every respect, it was a civil war,” says Rick Wise, executive director of the South Carolina Battleground Preservation Trust. “It was brother against brother, father against son, and it was brutal.”

Most of the bloodletting occurred in the “backcountry”—today’s Midlands and Upstate—in big battles like Camden, the Waxhaws, and Kings Mountain, but Charleston was the political epicenter of the fight.

Since its founding in 1670 as a British bastion against Spanish expansion from Florida, Charles Towne, as it was originally called, was indelibly linked to the mother country of England; folks here, and throughout the colonies, considered themselves British. Named for King Charles II of England, the city quickly became prosperous, importing enslaved West Africans to develop and work sprawling plantations across the Lowcountry.

By January 1776, the city, now called Charlestown, had grown into the fourth largest city in British North America, was the wealthiest, and was home to some of the richest men in the colonies. Those men made their fortunes growing indigo and rice, importing trade goods, and selling people into slavery by the thousands. They built palatial homes south of Broad Street to showcase their wealth, bound their families together through marriage, and created a new American aristocracy.

The planter elite produced a particular variety of rice known as “Carolina Gold” that was highly prized in European markets. The generated wealth spread to an emerging middle class of merchants and craftsmen. Together, they built a society in Charleston rivaling that of England. “Charleston was known as the London of America,” says Valerie Perry, interim director of museums for Historic Charleston Foundation. “It was a city that thrived on trade with Britain.”

The symbiotic relationship between Charleston and London flourished, but trouble lay ahead. The French and Indian War ended in 1763 and won for Britain the rich Ohio Valley, the upper Midwest, and much of Canada. Many Charlestonians, including William Moultrie, fought for the British against the French and their Native American allies, particularly the Cherokee. The war opened the heartland of the continent to American expansion but also left the government in London with crushing debt.

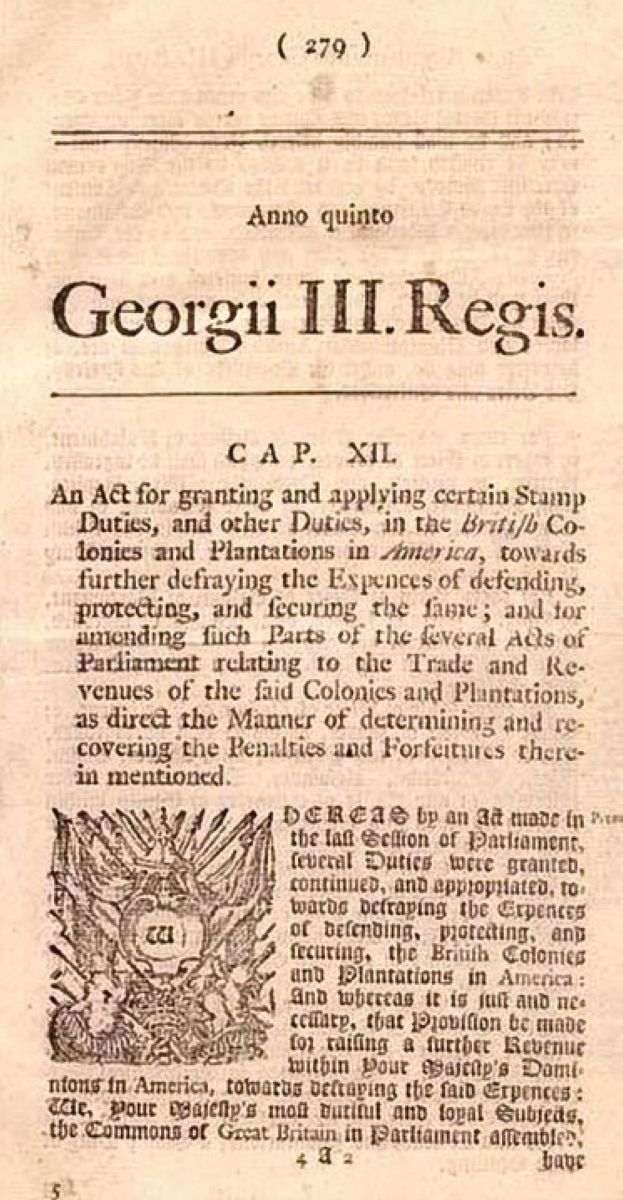

In 1765, the British Parliament and King George III imposed the Stamp Act—taxes on written documents such as court records, newspapers, and even playing cards. It was only fair that the colonies help pay for the war that presented them with such opportunities, the Crown reasoned. But the levy enraged many colonists. They were British citizens and now were being taxed without their consent. The seeds of rebellion were sown. “They probably couldn’t imagine not being part of the British empire,” says Elizabeth Chew, CEO of the South Carolina Historical Society. “But they were enraged by the way they were being treated by the British government.”

Protests against the Stamp Act were widespread. In Boston, they turned violent, capped by the March 1770 Boston Massacre, in which a colonial mob confronted British troops and five protesters were killed. While protests were also vigorous in Charleston, they were “not as large or as dramatic as in Boston,” says Sandra Slater, professor of history at the College of Charleston. “That’s why they don’t receive as much attention.”

In Charleston, the seeds of dissent against British taxation were cultivated in a cow pasture just north of the city, near today’s Alexander and East Bay streets, that was owned by Alexander Mazyck. There, under a live oak dubbed the Liberty Tree, protests against the Stamp Act began and would continue through the start of the Revolutionary War. The protests sprang not from the landed gentry, some of whom were hesitant to upset the balance with the nation that fed their fortunes, but by tradesmen and craftsmen. The “mechanics” as they were known, outraged by the new tax, united under the sobriquet “Sons of Liberty,” a secret society founded in Boston to protest the new tax. They held fiery rallies under the tree, marched through the streets, and burned effigies of British officials.

Christopher Gadsden, a merchant, aspiring planter, and revolutionary firebrand, became their leader. He helped unite elite merchants and planters with the mechanics and solidified Charleston’s opposition to the Stamp Act. To symbolize their resolve, Gadsden designed a flag, featuring a coiled serpent on a yellow field emblazoned with the words “Don’t Tread on Me,” that’s still popular today. He would present it to the Provincial Congress in February 1776. “Gadsden was the guy who stoked the coals of liberty in South Carolina more than anyone else,” says Tony Youmans, director of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon.

Amid the protests, the South Carolina Provincial Assembly—the governing body of colonialists under Royal Governor Lord Charles Montagu—began breaking ties with Britain, even issuing its own currency. The assembly met at the Statehouse at the corner at Broad and Meeting streets, which also housed the chambers of the royal governor. (Today, it is part of the Charleston County Judicial Center.) Montagu dissolved the assembly four times. However, without significant numbers of British troops to back up his edicts, his governance in South Carolina was effectively neutered, and he was recalled. His replacement, Lord William Campbell, was never able to regain control. “It was a constant battle with the Provincial Congress,” Borick says. “Things had already gone off the rails.”

Unlike Boston, the Crown’s military presence in Charleston was limited to a handful of British troops bolstered by local loyalists. Gradually, the Sons of Liberty eroded support for the British through economic boycotts, intimidation, and physical assaults with limited retaliation. The Sons of Liberty “put the hammer down,” Borick says. “They would strong-arm people who supported the Crown. Some were tarred and feathered. They did a tremendous job suppressing dissent against the Revolution.”

Eventually the Stamp Act was repealed, but the Crown tried other methods to raise funds to pay its war debt. Parliament issued an edict that only British tea could be imported into the colonies, and ships bulging with the commodity were sent to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. While the act actually lowered the price of tea in America, it included a three pence-a-pound tax that further inflamed tensions.

In 1773, about two weeks before protesters dressed as Native Americans famously threw crates of tea into Boston Harbor, Charleston held the nation’s first “tea party.” On December 3, a large crowd from across social classes led by Gadsden packed the Great Hall of the Exchange Building, where the tea was to be unloaded and sold. Overwhelmed, British authorities secretly moved the 257 chests—about 70,000 pounds of tea—from the cargo ship London to the Exchange’s basement where it remained unsold. It would later be seized by Americans to help fund the Revolution.

In reaction to the tea parties, the British Parliament passed a series of Intolerable Acts to punish the colonies, including blockading the port of Boston and revoking Massachusetts’ charter. The actions in Boston mortified Charleston’s rich planters and merchants, who became increasingly alarmed that the same retributions would occur locally. Two years later, in 1775, crowds again packed the Exchange to elect delegates to the First Continental Congress. Gadsden, Thomas Lynch Jr., Henry Middleton, and John and Edward Rutledge were chosen. “It was an extraordinary meeting,” Youmans says. “It was the birth of a national representative government in South Carolina.”

While the experience of Black people during the Revolution is often overlooked, it is integral to the story of the Revolution in Charleston. The city was the largest importer of enslaved Africans to North America, representing 40 percent of the colonial slave trade. Enslaved black people outnumbered whites in the colony at the time, and the spectre of slave rebellion had haunted plantation owners for decades. In 1739, during the Stono Rebellion, enslaved Africans killed more than 20 white people in an attempt to escape to French-controlled Florida, making it the largest uprising of enslaved people in the British colonies.

In August 1775, a free black man and avowed loyalist named Thomas Jeremiah was hanged and burned for allegedly attempting to incite a slave revolt. The charges were dubious. And in November, the British offered enslaved Black people freedom if they escaped and assisted the loyalist cause. Thousands took advantage of the offer.

The Dunmore Proclamation, as it was called, emboldened South Carolina leaders to join the North in armed rebellion. “The idea of arming enslaved people sent shock waves through South Carolina,” says Katherine Pemberton, chief of education and outreach for SC250, the state’s American Revolution Sestercentennial Commission. The planters “considered it a betrayal on the part of the English. They thought the enslaved were going to rise up and murder them in their beds.”

After the first shots of the Revolution were fired in Massachusetts at Lexington and Concord, Charlestonians began seizing arms and gunpowder, fearing British-sponsored slave uprisings and Native American attacks. The Provincial Congress formed an 13-member Council of Safety to organize and manage the rebellion. Patriots broke into munitions depots in the Charleston neck and the Statehouse and seized powder and guns. Militia units were called up to defend the state, swelled with recruits from the backcountry. “Without guns and gunpowder you can’t go to war,” Pemberton says.

Four regiments of soldiers were formed, along with accompanying artillery batteries. The 2nd South Carolina Regiment—organized in June 1775 and mustered into the Continental Army that November—was commanded by Moultrie and ordered to defend the city. That fall, the regiment overpowered the small British garrison at Fort Johnson on James Island and raised a huge, new flag designed by Moultrie featuring a white crescent on an indigo blue field. “It was the first time a South Carolina flag was raised over British Charleston,” Borick says.

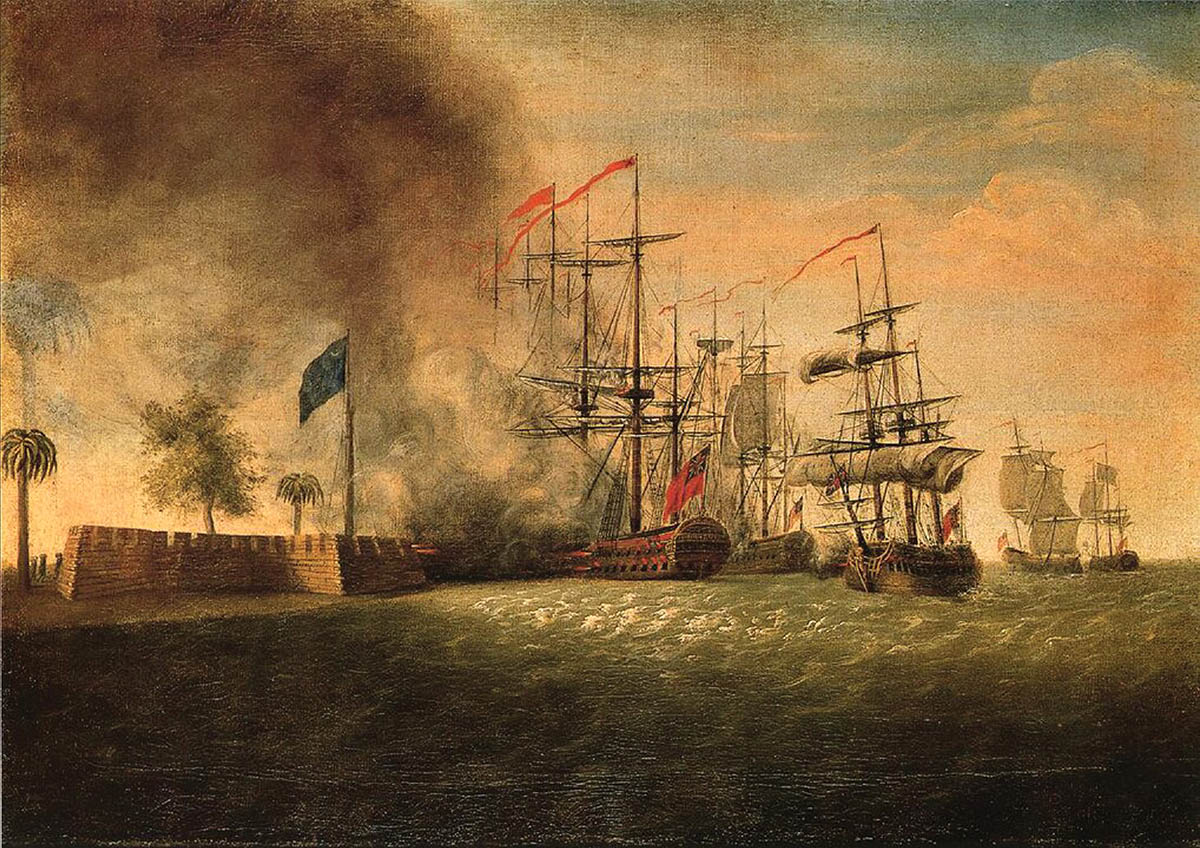

By the spring of 1776, word had reached the city that Parliament planned to reassert control of Charleston with a massive invasion. The British—wrongly assuming Southern colonies to be more supportive of the Crown than those in New England—sent a fleet of warships commanded by Admiral Sir Peter Parker and troops under General Sir Henry Clinton to seize the city as a base for an expanded war in the South.

Realizing the invasion was coming, South Carolina leaders ordered Moultrie to build a fort near the beach on Sullivan’s Island. He used palmetto logs and sand, which were readily available on the island. It was still under construction on June 28, 1776, when the British fleet appeared on the horizon.

Royal commanders landed troops on Long Island (Isle of Palms today), intending to storm the fort from the north as the vaunted British Navy, the world’s most powerful, would batter the fledgling fort from the seas. But the fibrous palmetto logs absorbed the naval bombardment, and Breach Inlet proved too treacherous to cross. The British were turned away, only to return in greater numbers in 1780 and take the city by siege. “It was the first big victory of the war in South Carolina and one of the biggest in the Revolution,” Borick says. “It galvanized support for independence.”

The Battle of Sullivan’s Island buoyed the nation in its infancy and created the iconic symbols of South Carolina today. The palmetto trees used to build Fort Sullivan were added to Moultrie’s indigo flag to become the state flag. Carolina Day is celebrated each year to commemorate the stunning victory.

The Declaration of Independence would be signed six days after the battle by members of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. On August 5, 1776, it would be read in Charleston at the Statehouse, the Exchange, and under the Liberty Tree. The signing of the Declaration would become the seminal event in the birth of the United States, signaling the beginning of a long and bloody war for liberty. It would also cement South Carolina as a powerful player in the political life of a new nation.

“No event has seemed to diffuse more general satisfaction among the people,” wrote the Rev. William Tennett at the time. A Charleston-based Presbyterian minister, he was an avid patriot who traveled the region advocating religious equality. “This seems to be designed as a most important epocha [sic] in the history of South Carolina… from this day it is no longer to be considered as a colony but as a state.”

Miles Brewton House

One of America’s finest Georgian townhouses, this private home served as headquarters for British officers—and its imposing gates still display chevaux-de-frise defensive spikes. Not open to the public; admired from the street.

27 King St.

Old Exchange Building & Provost Dungeon

Once the center of colonial trade, this site witnessed the blocking of British tea, the election of Continental Congress delegates, and South Carolina’s ratification of the US Constitution. Its holdings include a rare “wet ink” copy of the Declaration of Independence. 122 East Bay St., oldexchange.org

Get a tour of The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon and learn about Charleston's resistance to the 1773 Tea Act:

Heyward-Washington House

Built in 1772 for Thomas Heyward Jr., a signer of the Declaration, this historic house, owned and managed by The Charleston Museum, later hosted President George Washington during his 1791 visit. Tour furnished rooms, a period kitchen house, and formal gardens. A new audio tour highlights Revolutionary history. 87 Church St., charlestonmuseum.org

Old South Carolina Statehouse Site

Now part of the Charleston County Judicial Center, this is where the Declaration of Independence was first read in South Carolina. The restored façade survives, along with the 1770 statue of William Pitt, a British supporter of colonial rights.

84 Broad St.

Gadsden’s Wharf / International African American Museum

Erected near the site of patriot and enslaver Christopher Gadsden’s wharf, where thousands of enslaved Africans first arrived in North America, the museum traces the African diaspora and offers a Family History Center for genealogical discovery. 14 Wharfside St., iaamuseum.org

Liberty Tree Site

The original live oak in today’s Ansonborough neighborhood, where the Sons of Liberty gathered in the 1760s and ’70s, was cut down by British troops. A bronze marker commemorates the location. 80 Alexander St.

Fort Johnson

Seized by patriot militia in 1775, this site is where the famous “Liberty” flag—precursor to the South Carolina state flag—was first raised. A 1765 brick powder magazine remains. 217 Fort Johnson Rd., James Island (SC Department of Natural Resources Campus) dnr.sc.gov/marine/mrri/ftjohnson.html

Fort Moultrie

On Sullivan’s Island, this fortification occupies the site of Fort Sullivan, where palmetto-log walls helped repel the British in 1776. The National Park Service site interprets the fort’s role from the Revolution through World War II. 1214 Middle St., Sullivan’s Island; nps.gov/fosu

Mark your calendars: this year, the SC American Revolution Sestercentennial Commission’s local chapter, SC250 Charleston, along with an array of local institutions are present a host of programs, exhibitions, and celebrations for this auspicious anniversary of the birth of the United States.

Through Summer 2027 | “Voices of the Revolution in South Carolina”

Housed in the landmark Fireproof Building, the SC Historical Society Museum unveiled this small but insightful exhibit last fall. It highlights the Revolution through personal items—such as a powder horn believed to have belonged to Francis Marion—and stories of women, Native Americans, and African Americans. South Carolina Historical Society Museum, 100 Meeting St., schistory.org

January 31- September 20 | “Ringleaders of Rebellion: Charleston in Revolt, 1775–1783”

The Charleston Museum presents this new exhibition exploring the city’s pivotal role in the Revolution, featuring artifacts connected to Francis Marion, British and American soldiers, and everyday Charlestonians. The museum—founded in 1773 and considered the nation’s first—also includes the permanent exhibit “Becoming Americans: Charleston in the Revolution.” The Charleston Museum, 360 Meeting St., charlestonmuseum.org

April 1-December 2029 | “Conversations of Freedom”

Step into the Revolutionary era at Middleton Place where this exhibition illuminates the lived experiences of Declaration of Independence signer Arthur Middleton, his household, and the individuals they enslaved. Through varied viewpoints, it examines how the period’s evolving notions of liberty influenced—and sometimes complicated—their daily lives. Middleton Place, 4300 Ashley River Rd., middletonplace.org

May 14–17 |Consortium on the Revolutionary Era Conference

This scholarly gathering at the College of Charleston will examine the American Revolution within the broader Atlantic world—timed to the 250th anniversary. College of Charleston, various campus venues, claw.cofc.edu

June 20–22 | Legacy Concert Series

A patriotic three-night music celebration launching two weeks of 250th anniversary programming. Credit One Stadium, 161 Seven Farms Dr., Daniel Island, www.sc250charleston.org

June 26 | A Conversation with Rick Atkinson

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Rick Atkinson discusses The Fate of the Day (Crown, 2025), his newest volume on the war’s Southern campaigns, including Charleston. Dock Street Theatre, 135 Church St., www.sc250charleston.org

June 27 | Official Drone Show

A dramatic light-show tribute over Charleston Harbor will honor Carolina Day and the Battle of Sullivan’s Island. Find the best viewing along the harborfront and Waterfront Park. www.sc250charleston.org

June 27 | Legacy Gala

This black-tie evening at The Cooper features dinner, period dancing, and an awards presentation. Attendees are encouraged to wear military “Mess Night” attire or historical costume. The Cooper Hotel, 176 Concord St., www.sc250charleston.org

June 28 | A Grand Carolina Day Commemoration

This ceremonial remembrance at Fort Moultrie includes bell-ringing, wreath-laying, military honors, and living-history demonstrations. Fort Moultrie, 1214 Middle St., Sullivan’s Island; www.nps.gov/fosu

June 28–July 5 | Heritage 250 Expo

Marion Square becomes a “living museum” with music, storytelling, crafts, historic reenactors, and panel discussions celebrating Charleston’s Revolutionary legacy. Marion Square, 329 Meeting St., www.sc250charleston.org

July 4 | Waterfront Independence Day Celebration

Citywide festivities include family-friendly programming and a coordinated fireworks display over the peninsula. Various locations. www.charleston-sc.gov