Though Noisette died in April 1835, the roses named for him commemorate the role he and gardener John Champneys played in rose history

With gardens springing to life, you may find bits of Charleston horticultural history unfurling wherever roses bloom. Not just across the city or the continent, but in Europe and France, especially, Noisette roses are climbing and bursting into pom-pom like blossoms. As they attract the eye and scent the air, they, in their very existence, reference the Lowcountry.

South of the city, in the early 19th century, gardener John Champneys (1743-1820) hybridized two roses, the ‘Musk’ and ‘Old Blush,’ to create a stunning remontant varietal—the first “ever-blooming” rose in the western world—promptly dubbed ‘Champney’s Pink Cluster’ to honor him.

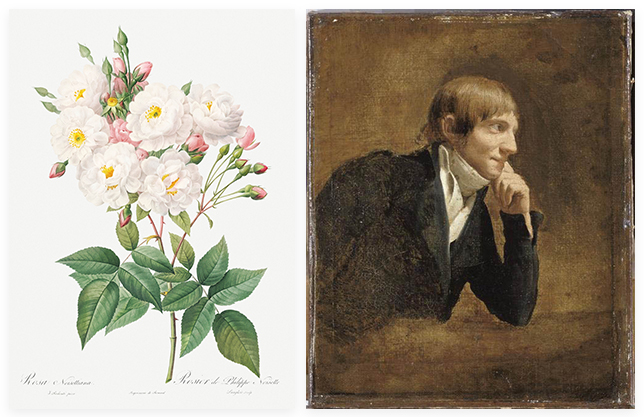

Noisette roses gained popularity in Europe after artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté (right) painted the blooms (left).

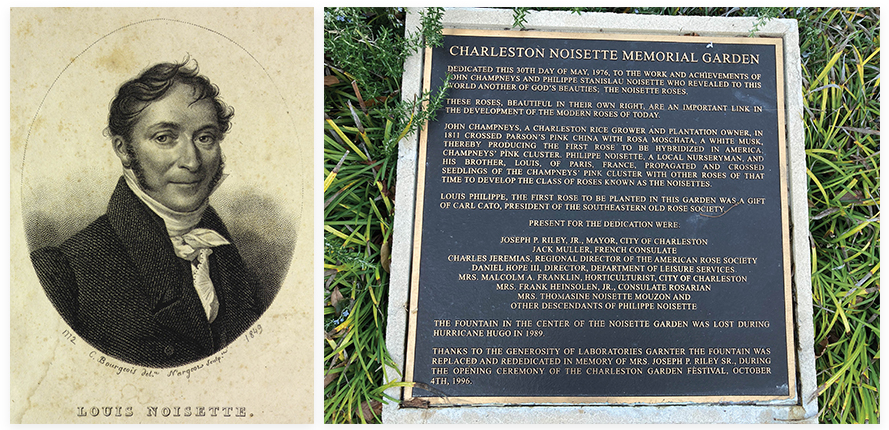

Around the same time, Philippe Stanislas Noisette, born in France in 1793, son of Joseph Noisette—gardener to the nobleman who would become Louis XVIII—arrived in Charleston from Haiti. Historians aren’t sure whether Noisette supplied the roses to Champneys or if Champneys got the seeds elsewhere and then shared the new breed. We do know that Noisette was hired to direct the newly established Botanical Gardens in Charleston, while maintaining his own acres of plants on what today is upper Rutledge Avenue.

(Left) The hybrid had been sent to gardener Louis Noisette from his brother Philippe in Charleston; (Right) A Gaillard Center garden is dedicated to Noisette and Champneys.

It’s well documented that in 1814 Noisette sent a hybridized rose to his brother Louis Claude, a gardener in France. There, its splendor gained immediate popularity. When Pierre-Joseph Redouté, the most acclaimed flower painter of his era, rendered it under the title ‘Blush Noisette,’ it became even more well-known, and soon roses called “Noisettes” were planted across Europe.

Noisette died 190 years ago on April 7, 1835, and was buried in St. Mary’s cemetery. While his tombstone has disappeared, the roses named for him act as elegant epitaphs, blooming in his memory and commemorating the part he—and Champneys—played in rose history.