“When you ask people today to name a Southern drink, bourbon is almost certainly the first word that springs to their tongues,” Robert F. Moss writes in the introduction to Southern Spirits, released this month by Ten Speed Press ($25). But as the local writer goes on to prove, bourbon hasn’t been as singular as history purports. “Yes, plenty of Southerners sipped mint juleps. But contrary to the misty myths of the Old South, they usually weren’t sitting on the veranda of a white-columned plantation house, and the liquor in their tumbler was not bourbon.” So what have we been drinking since the 17th century?

For starters, ale. And when provisions ran out and became too costly to ship, cider and brandy, too. Distilling began early on, and as trade in the Caribbean picked up, rum was the word—particularly in harbor cities like Charleston. Irish and Scottish immigrants brought with them the knowledge to make whiskey, though instead of barley, corn was most readily available, followed by rye. Owning Madeira wine was a status symbol for society folk—though we know what happened to those caches postbellum.

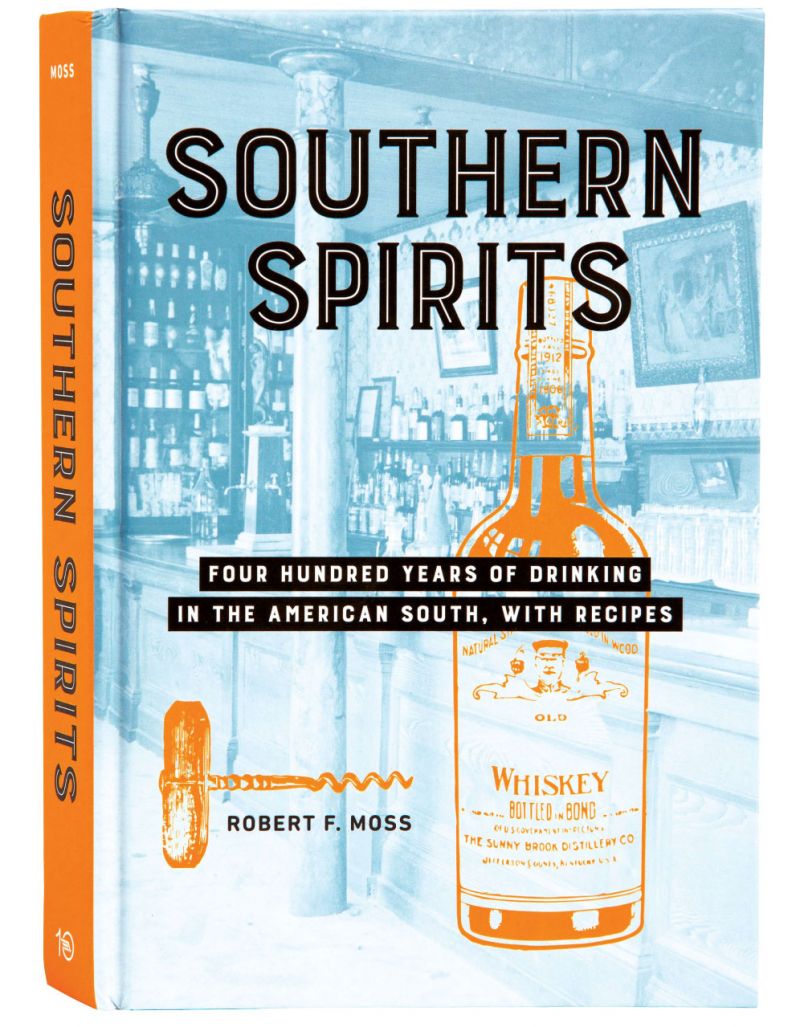

Moss, a thorough historian who has written extensively on barbecue, continues his more-than-bourbon argument through Prohibition and ends with today’s craft-distilling trend. Each chapter opens with a recipe corresponding to the period discussed within, including notes for preparation and finding authentic ingredients.

The author doesn’t shy away from the South’s less desirable history—for instance, recounting the slave owner’s use of alcohol as a means for control, as well as the Southern temperance movement’s ties to white supremacy. Women, however, don’t factor in the text much after the American Revolution. Writing, “As brewing and distilling grew more commercial in nature, alcohol production moved from the woman’s realm of cooking and housekeeping into the male-dominated world of trade,” Moss more or less concludes the female account. Still, a silver lining can be found: there’s room for more, perhaps in a just-as-fascinating follow-up. After all, thirsty scholars can always hope for another round.