Inside the renovated South of Broad residence that dates back to the late 1700s

Leaning on a marble mantelpiece with scars from Charleston’s Great Fire of 1861 is literally touching history. So, it can be a little jarring when you walk into the kitchen in a home with this much authentic patina and find a 1980s Jen-Air range. That juxtaposition in a circa-1797 single house South of Broad led the homeowners to what they originally thought would be a limited renovation project.

“It all started as a kitchen remodel,” explains Charleston-based architect Glenn Keyes. “The clients had bought the house about 15 years prior but had not really done much to it.” The more than 200-year-old structure last saw a refresh in the 1980s, with little consideration for the past; it was more about adding modern conveniences. “Additions to these old houses are almost always because of lifestyle changes,” explains interior designer Tammy Connor, who worked with Keyes on the project. “Homeowners want a family room that’s open to a kitchen, or a bigger bathroom, or more closets”—concepts that weren’t part of early life in the city.

In this 18th-century residence, what started as a kitchen renovation to increase functionality grew to include an expansion of the primary bedroom’s dressing room and bath, and then turned into a two-year-long, top-to-bottom rehabilitation. “Every room was touched,” says Connor.

The “Paige” sofa from Kerry Joyce upholstered in rose velvet adds warmth to the formal living room, where neutral colors provide a cozy space. This was originally the dining room, and the homeowners decided to switch the uses to create more living space in the back of the elongated house.

A Fresh Start

The grand home had been through a lot in its two centuries and was “tired,” says Keyes, but it still had good bones. From its three-quarters of an acre lot and three piazzas (“They’re so large, they’re possibly the deepest piazzas in town,” notes Keyes) to the original heart-pine flooring, marble fireplaces, and grand ceiling medallions, the home had plenty of features to work with. Keyes’s main concern was staying true to the Greek Revival architecture and retaining as much of that character as possible. “We revere the historic fabric—it has the patina of time,” he explains. “Those nicks and dents from kids playing illustrate how many generations have lived in this house.”

The biggest challenge was finding a way to creatively accommodate a more livable primary bedroom suite. The four-bedroom, 9,000-square-foot home had plenty of space, but its Charleston single configuration—one room wide, tall and skinny—left little room for expansion. Keyes decided to add on to the rear of the house, building upon an earlier addition that now serves as a sitting room.

Most early Charleston residences had a separate dependency for the kitchen and other utilities. With the advent of plumbing, people started connecting these structures to the main house with a “hyphen.” Keyes used the hyphen addition as the foundation for the dressing room and bathroom adjacent to the owners’ suite.

He expanded a small closet in the bedroom and built another closet behind that, “stepping it back, so it recedes from the earlier one-story building,” he explains. To make it blend, Keyes picked up on existing elements, such as replicating the siding of the earlier addition beneath it. “You don’t want to make it look like it was original to the house,” explains Keyes. “You want to be able to read the building, see how it evolved. You’re not trying to fool people into thinking it was from 1797.”

Additionally, the team recaptured some space on the ground level, converting storage into a billiard room and a sitting room. The rest of the house was restored, modernizing the infrastructure—heating, air conditioning, electrical, and plumbing—without removing any of the historic fabric.

The same philosophy applied to the interiors, which were wholly redone, with new wall coverings, paint, furniture, light fixtures, and artwork—all in keeping with the period while infusing the owners’ personalities throughout. “The Lowcountry is such a big part of their life; they grew up here and are very much connected with the land,” says Connor, explaining the dominance of marshy greens and textured grasses in the home’s palette.

Bathing Beauty: A figurative oil painting by Danish artist Louise C. Fenne presides over the Waterworks “Empire” soaking tub in the primary bathroom. (Right) A 19th-century bell jar fixture

from Tucker Payne Antiques lights the bathroom, with its elegant custom cabinetry by F.M. Jessen Inc. in “Gimlet” by C2 Paint.

While almost everything Connor selected was new to her clients, many pieces have a history tracing back to the 18th century. “The house tells you what it wants,” says the designer, who sourced antiques, such as the circa-1820s Regency mahogany dining table and the Jacobean-style buffet table, from dealers in Charleston and along the East Coast.

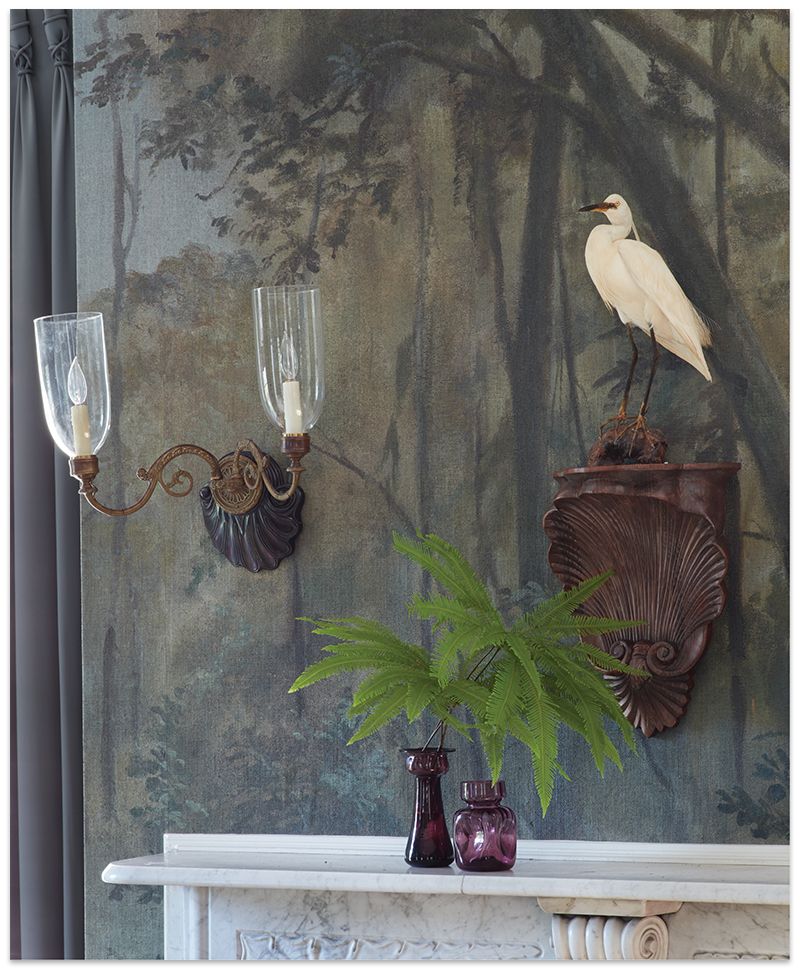

A few of the homeowners’ pieces remain. A collection of traditional English stoneware “gluggle jugs” (fish-shaped vases) paired with antique plates is artfully displayed on the rear entryway wall, and a dramatic Lowcountry landscape painted by local artist Mickey Williams dominates the den. Here, the walls are paneled in a warm cypress, a theme reflected by depictions of actual cypress trees in the dining room at the front of the house. In that space, a dark, evocative mural of the towering trees soaking up the marsh waters creates the moody palette that’s continued throughout the interiors.

Painted by Atlanta-based artist Raymond Goins on burlap panels, the cypress swamp scenes cocoon the dining room. “It roots the house in a sense of place, connecting what’s important to the homeowners,” says Connor. Large windows on three sides provide plenty of natural light during the day, avoiding a potential cave effect. Then, at night, by candlelight, “it’s magical,” she notes.

In the kitchen, Connor and Keyes retained as much of the original architecture as possible, going to great lengths to conceal modern conveniences. Custom paneled cabinets painted in a warm white hide the refrigerator, and the original brick wall houses a ceramic farmhouse sink. This wall presented a design challenge due to a step-back in a crucial spot. But Connor embraced and highlighted the quirk with an oil painting by Jonathan Koch from Ann Long Fine Art. “The architecture is your starting point,” says Connor. “It informs the design and allows the house to tell its story.”

The home’s wide triple piazzas are atypically large for the period, according to architect Glenn Keyes. They were likely added in the 1850s when the structure was updated with Greek Revival detailing.

The lower piazza (above) is the formal entrance.

Upstairs in the addition, Connor took cues from the old to make the new feel part of the original house. “We aim to design so that it’s inviting and comfortable but true to the history of the period, just a little bit lighter and fresher,” she explains. Bright drapes and rugs add a touch of whimsy to the rooms dominated by 19th-century European antiques. The custom cabinetry in the new bathroom echoes that of the kitchen but with a lighter touch, and a grand, freestanding Waterworks “Empire” tub offers a splash of luxury.

For a project that started as a modest remodel and morphed into a complete restoration of one of Charleston’s most historic homes, it would be easy to be overwhelmed by the responsibility of preserving history. For Keyes, however, who has become a master at this art, the path to resurrection is a simple one. “We try to take care of what’s there and enhance the beauty and function of it without negatively impacting the historic structure,” he says. “That’s what we do.”