Find out what why it’s significant

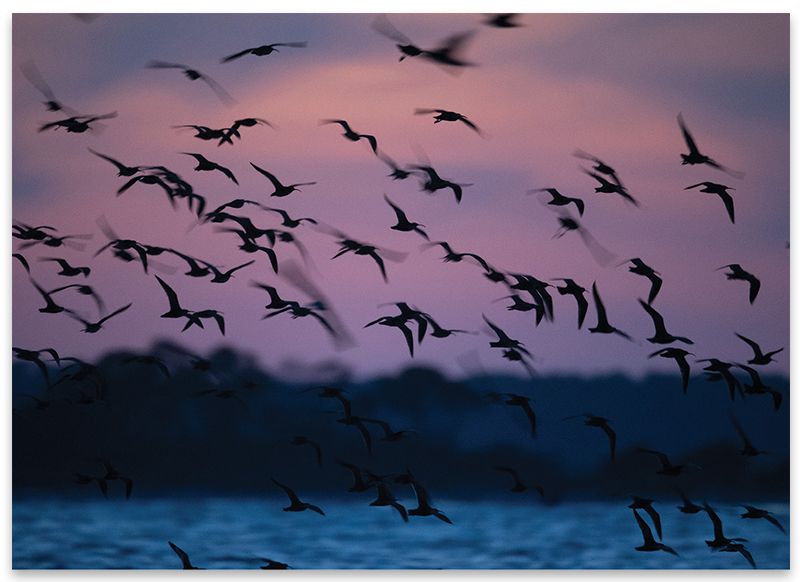

In the spring, whimbrel flock to Deveaux Bank at dusk to roost before flying north to the Arctic.

Lowcountry boaters and birders have long known that Deveaux Bank is special. The shifting 200-acre sandbar juts into the Atlantic from Botany Bay, just off the southernmost point of Seabrook Island. Half of South Carolina’s brown pelican population nests here, along with huge numbers of threatened terns, plovers, and egrets. But despite ample awareness and attention on Deveaux’s bird population, nearly 20,000 whimbrel literally flew under the radar here for years.

Whimbrel are a type of curlew with long, curved beaks that allow them to forage in mud flats for crabs and mollusks. The 40,000 birds that remain in the Atlantic population fly from South America to the Arctic each spring. Once they arrive, they need enough stored energy to lay eggs and protect their nest. That’s where the Lowcountry comes in—each May, whimbrel stop along the Southeast coast for about a month of heavy eating.

Watch a video as the whimbrels come to roost at Deveaux Bank

Back in 2014, South Carolina DNR biologist Felicia Sanders saw large groups of whimbrel leaving Deveaux at dawn and suspected the site might be a significant night roost for the species. Over the next few years, she organized bird counts and relayed her suspicion to Andy Johnson, a filmmaker with the Conservation Media Center at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

By 2019, they’d confirmed the staggering truth: around 19,500 whimbrel congregate on Deveaux each evening, making their nightly roost the largest concentration of the declining whimbrel population in the world. “It was almost too much to even suggest and be believed,” says Johnson, who spent a month on Deveaux filming birds arrive from their daily foraging grounds that stretch from Charleston south to Hilton Head. Johnson’s team documented the spectacle in a nine-minute video used to share the discovery with the world in June.

To capture large groups of whimbrel taking flight at dawn, Johnson hunkered down for restless nights among Deveaux’s sand flats. “There are times when picking your blind spot, five feet can be the difference between getting your shot or having your blind flooded with salt water and all your batteries shorting out,” he recalls.

For Johnson and Sanders, the opportunity to document and share an incredible finding was worth some discomfort. Although Deveaux constantly changes shape, gaining and losing mass, it’s been steadily growing for more than two decades, and the presence of the whimbrel precedes Sanders’ discovery. Although a hurricane could wipe Deveaux from the map for a decade, right now, this shrubby, grassy island is one of the most critical spots for the survival of the birds along the entire Atlantic coast.

Sanders emphasizes the importance of closures that protect birds and limit humans to exploring below the high tide line. Those rules have allowed species like pelicans to begin a rebound of their population, and there’s optimism they could do the same for the whimbrels. “When we organized an official count and realized it was nearly 20,000 whimbrel, I almost couldn’t believe that it was true,” says Sanders. “To find this many birds in one place—of a species that’s been declining—it gives you hope.”