Fordham's fourth book, "The 1895 Segregation Fight in South Carolina" is being released this month

Damon Fordham is a treasure hunter and storyteller, digging up long untold facts and sharing them as a tour guide, an author, and an adjunct history professor at The Citadel. The historian strongly believes that by going beyond the traditional narrative, he can change people’s perspectives. After all, he says, “You don’t understand what is until you understand what was, and that will give you an idea of what could be.”

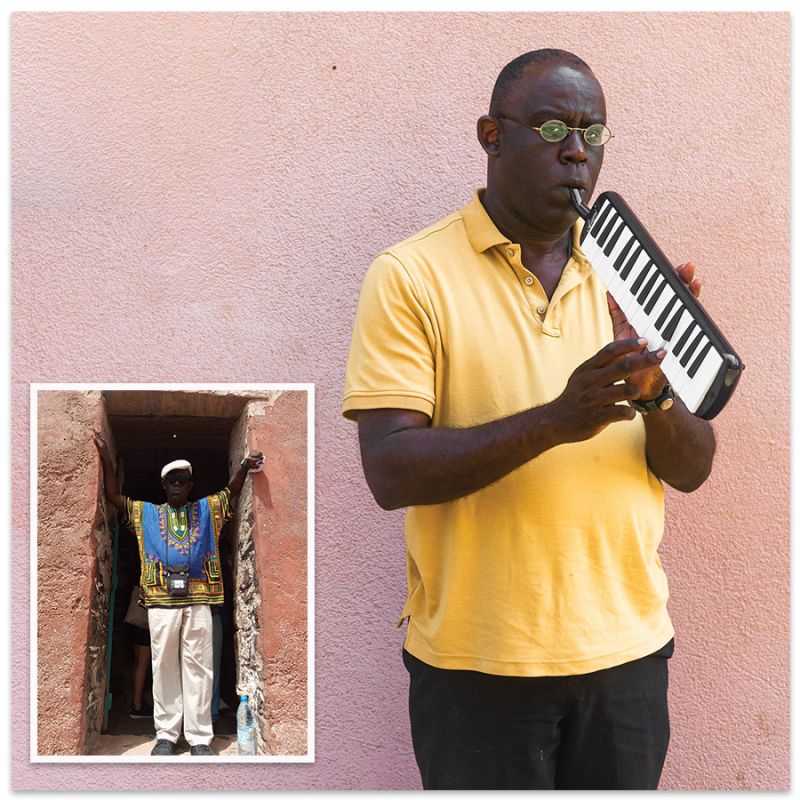

On the “Lost Stories of Black Charleston” walking tours he’s led from Buxton Books since 2016, Fordham tells visitors about the origins of Porgy & Bess, Briggs v. Elliott, and Denmark Vesey’s slave rebellion, sometimes playing tunes such as “Summertime” on his melodica, and rarely giving the same tour twice since he says he’s always discovering new information.

In his fourth book, The 1895 Segregation Fight in South Carolina (The History Press, July 2022), Fordham compiles for the first time the remarkable speeches that six African American officials delivered defending their rights during the 1895 state constitutional convention, which severely limited African Americans’ right to vote after Reconstruction and paved the way for Jim Crow segregation.

Here, Fordham talks about his book as well as a recent life-changing trip to West Africa

CM: In your book, you compile the speeches that six African Americans made at the 1895 state constitutional convention. What drew you to those words?

DF: There was a book I read 20 years ago called Lift Every Voice, African American Oratory from 1797 to 1901, and one of the speeches by Thomas Miller, who was the founding president of South Carolina State University, told about how he and other Black leaders at that time spoke up against Benjamin Tillman, who was the architect of Jim Crow and the segregation of South Carolina. I said, ’Whoa, I never heard about that,’ and then I read what he said, and it just blew me away—his eloquence as well as his courage in doing that back then.

CM: Why was it important for you to write this book?

DF: Many people believe that nobody did anything in regard to the liberation of Black people and their condition in this country from Frederick Douglass up until Martin Luther King Jr. This book lets people know when these things were happening, African Americans got up and did something, and that’s not common knowledge. So often people feel a sense of defeatism, and as Malcolm X said in 1962, you can never do anything, if you think you never did anything. That’s why I think the book is important.

CM: Tell us about your experience in Senegal.

DF: Gorée Island was a slave port strategically located on the farthest western point of Africa so that it would have the quickest access to the Americas. They have the “Door of No Return” (left), where people were marched in chains to the slave ships. It is impossible to walk through it without having some sort of emotional reaction.

CM: What do you hope people take away from your “Lost Stories of Black Charleston” walking tour?

DF: I do a lot of independent research, and I try to find the buried stories in old newspapers, magazines, and oral histories that the average person doesn’t already know. I expand on them to help broaden people’s understanding of history because you don’t understand what is until you understand what was, and that will give you an idea of what could be. It’s to help open their perspectives and help people understand there’s more than the traditional narrative.

CM: Is there a part of your tour that people seem to find the most interesting?

DF: When I make the connectiion between the Denmak Vesey slave rebellion of 1822 and the terrorist massacre at Mother Emanuel AME Church; that’s usually how I end the tour. In 1822 you had the attempted Denmark Vesey slave rebellion in Charleston. Denmark Vesey was a free man, who read the Bible, the constitution, and history books, and tried to encourage a slave rebellion in Charleston. But one of his followers told the wrong man, who told the authorities, and that was shut down. In the course of that, the church that he operated out of, Hempstead AME church, was taken down, but several years later a minister named Henry Harvey Cain came to Charleston and organized a new church out of Vesey’s old church, which became Mother Emanuel.

CM: Do you have a favorite passage from the speeches that are included in your book?

DF: William J. Whipper—who was a lawyer who once practiced on Broad Street and whose great-great-nephew Seth Whipper is a magistrate now in North Charleston—said to Benjamin Tillman on November 1, 1895: “The car of Negro process is coming and yet you want to halt it, but I tell you the Negro will rise, crush us as you may, phoenix-like we will rise again. We cannot be kept down forever. It is not the nature of things for people to be that way.” That he would get up in spite of being insulted, and threatened and say that in 1895, the courage behind all of that just touched my heart. It’s a human story of resistance.

CM: Tell us more about your trip to Africa.

DF: We went to two villages in the outback, and at one point we went to the Fulani people who were in the lower southern region of Senegal. They kept pointing at me and saying in their language “Wolof.” I asked our translator, Seikou Kassama, what they were talking about, and he told me that they think you are of the Wolof tribe, and they are surprised to see you speak in English and be with the Americans. I said to them through him that I’m an American, but I appreciate the fact that they claim me, so I proudly claim all of them. Several days after this, we went to the University of Dakar, and they had this young docent. Seikou called me over and he said, ’Professor, meet your Wolof sister.’ Now, most Black Americans long to learn what tribal group they come from so that was an extremely emotional moment, and the young lady and I agreed to stay in touch. I did some research on the Wolofs and found that they were prominent as what were known as griots. These were the people who passed down oral histories in large gatherings through the spoken word, and they did so in an animated style with musical background. For years, I’ve been doing pretty much the same thing, I thought because my dad was an animated storyteller. When I learned that fact, I see that I come to this thing both honestly and ancestorally. You can say that I went to Africa and found out a whole lot more than what I intended to find.

Born: Spartanburg

Lives: Mount Pleasant

Education: Undergraduate degree in business management from USC, master of US history from College of Charleston

Career: Adjunct professor of history at The Citadel, tour guide, and author

Favorite tour stop: Site of the Charleston Club House (now the J. Waties Waring Judicial Center), where Reconstruction started in Charleston in 1868 with Black and white legislators

If you go:

Book Launch Event

Monday, July 25

5:30 to 7 p.m.

Buxton Books, 160 King St.

RSVPs are not required, but recommended to rsvp@buxtonbooks.com