Enslaved man Nicholas Kelly led the uprising, the first of its magnitude in the South

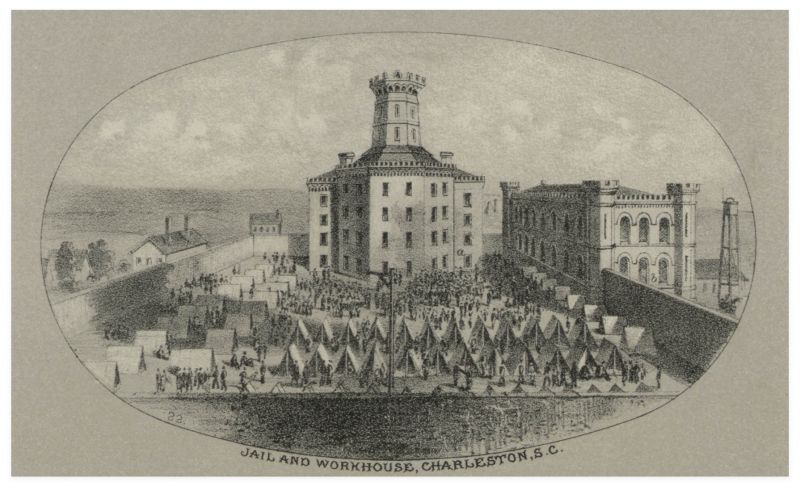

Enslaved people were imprisoned at the Workhouse on Magazine Street.

This month, lovers of liberty can mark Independence Day on July 4, and the Fall of the Bastille in Paris on July 14. But the Charleston Workhouse Rebellion of July 13, 1849, also merits remembering.

Nicholas Kelly, born locally circa 1822, had been jailed at the Workhouse (no longer standing) on Magazine Street for behavior his enslaver deemed unsuitable. He had worked as a plasterer, been sent to and retrieved from New Orleans, and according to some accounts, been cheated out of the money he had paid to his enslaver to gain freedom for himself and his family. Imprisoned for months, Kelly physically intervened when an incarcerated woman he knew, or was related to, was to be removed.

After Nicholas Kelly led a rebellion there, a white mob attempted to destroy the nearby Calvary Episcopal Church.

Workhouse staff retreated, called in the mayor, and later, the city guard, and St. Michael’s bells began to ring in warning. Armed with pickaxes, sledgehammers, stones, and other weapons, more than 30 enslaved men escaped out of the gates with Kelly. An uprising of that magnitude had never happened before in the city or the South. Kelly and most of his band were caught quickly and arrested; all the escapees were recaptured within a few weeks. On the day following the rebellion, the 60th anniversary of the fall of the Bastille, Kelly was sentenced to death, and other leaders were hanged soon thereafter.

(Left) The current church on Line Street; and (right) a historical marker at the site.

In response, a white mob nearly destroyed the nearby Calvary Episcopal Church, which was being built on the corner of Beaufain and Wilson streets to accommodate a predominantly Black congregation. Today, the church stands on Line Street, a partner in the Episcopal Diocese’s racial justice and reconciliation movement.