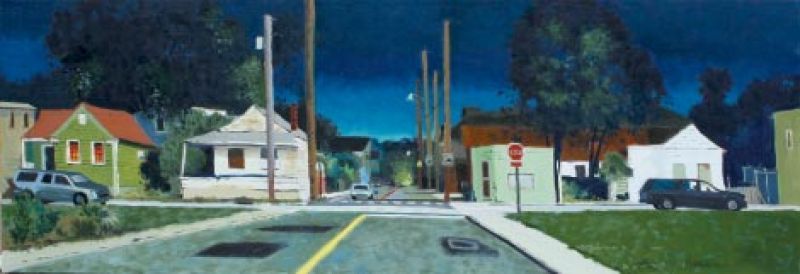

Johnson Hagood drives around Charleston’s East Side after dark looking for inspiration. He’s not interested in painting Rainbow Row or The Battery in oil and pastel. Instead, he seeks beauty in the overlooked parts of his hometown—the corner of Lee and Nassau streets, for example, which City at Night depicts as an intersection reaching out in the shape of a cross, a warm light at the end of the road. “Sooner or later, all of these areas will be gentrified. I’m trying to capture parts of the South that one day won’t be here,” says Hagood, who grew up drawing and painting at the Gibbes Studio of Art School before studying with artists Michael Tyzack and William Halsey at the College of Charleston.

Describing his style as “luminous,” the painter is influenced by 19th-century Hudson River School painters such as Martin Johnson Heade, who explored the effects of light on landscapes. Though Hagood got his start painting abstracts and then impressionist pieces, by the mid-1990s, he was experimenting with luminosity in his landscape paintings of the Lowcountry’s barrier islands. It wasn’t until 2009 that nocturnal painters Frederic Remington and Charles Rollo Peters inspired the artist—who’s collected more than 500 books on American art—to try nighttime scenes. City at Night was his first large attempt. “The Greenville County Museum of Art saw that piece, and we agreed that I would paint some of the transitional areas of Greenville at night as well as during the day,” explains Hagood. He set to work, not only on painting the Upstate city, but also the peninsula’s East Side and “the little shacks on James Island, Folly Beach, and the outlying islands,” he says. “No one has spent millions of dollars turning these homes into grand palaces—people just live there, and that’s the beauty of it.”

“Johnson’s contemporary ‘luminism’ is unique among landscape painters in South Carolina,” Thomas W. Styron, director of the Greenville County Museum of Art, explains. “His works are rendered with his keen eye for the effects of color on otherwise mundane architecture.” Among the 12 pieces Hagood created for the January 2012 Greenville exhibit is Poinsett & Shaw, Greenville, which shows several flat-roofed buildings sprinkled with graffiti sitting on a quiet corner. A white arrow painted on the street points at the viewer in a way that seems playful and beckoning. Telephone poles stretch into the distance, lingering in the mind of the viewer long after she or he has turned away.

“I’m trying to capture a fleeting moment on paper or canvas, so I don’t make anything overt,” says Hagood. “You have to, and should, look at a painting for a while to really understand it. If it evokes feeling in you, or triggers some far-away memory, then I’ve done what I set out to do.”