A drone shot of a rising spring tide (or “king tide”) near Sullivan’s Island in April 2017; photograph by Jason Ogden

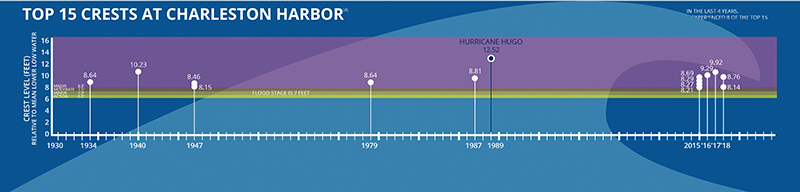

Flash back to October 2015, when the dregs of Hurricane Joaquin, better known as the “1,000-year flood,” dumped some 4.4 trillion gallons of water on the state of South Carolina, with 23.4 inches as measured on James Island, causing 157 local road closures and untold numbers of headaches, and an estimated $2 billion in lost revenue statewide. A year later, Matthew splashed into town, and then in 2017, Irma unleashed more floods. In between, intermittent “nuisance” flood events (also called “sunny-day flooding” related to king tides rather than major storms) wreaked havoc—38 times in 2015, more than three times what Charleston experienced in 2000.

This triple whammy has raised awareness and alarm in a new way, suggests Jacob Lindsey, the City of Charleston’s Director of Planning, Preservation, and Sustainability. “A 1,000-year flood people can write off as a freak of nature. A second event raises an eyebrow or two, but can still be dismissed as an aberration. But when things come in threes, people start paying attention. They understand there’s a problem,” Lindsey says. And for those inclined to pay heed to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) scientists, the red flags go way up. Considering its sea level rise predictions, NOAA projects that by 2045, Charleston will experience tidal flooding 180 days out of the year.

(Top and bottom left) The aptly named Water and President streets often flood with storm water and king tides.(Right) Wet Point Gardens: A hurricane in 1940 turned White Point Gardens into a waterway. Two men wade at the corner of Meeting and South Battery, and cars are flooded at the end of King Street and South Battery.

Old Issue, New Urgency

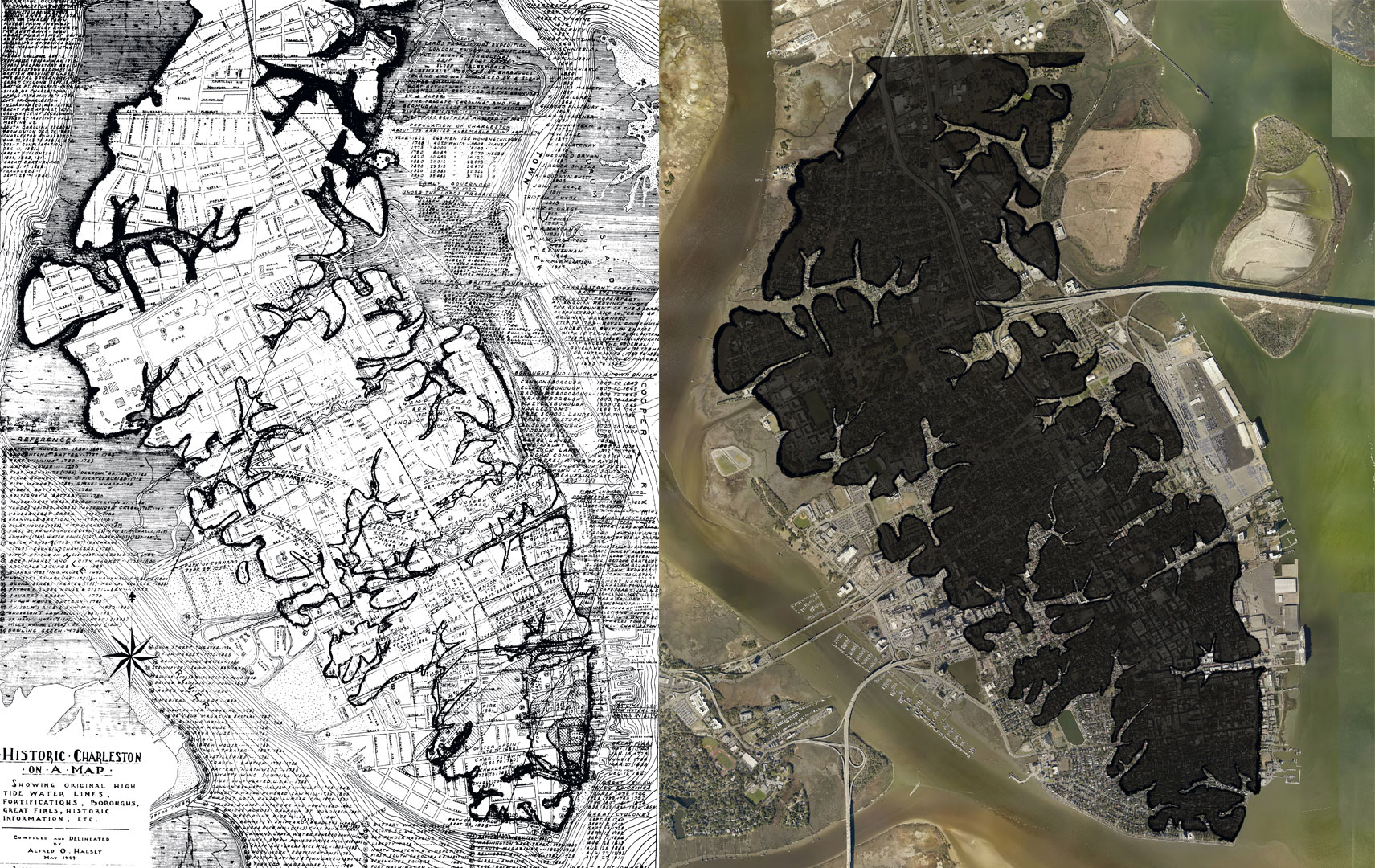

In truth, however, Charlestonians have been dealing with water issues, whether natural or man-made, for centuries. In 1785, two years after the city’s incorporation, plans for a protective sea wall were put in place. In 1788, Daniel’s Creek was filled to create Market Street, and shortly thereafter, Vanderhorst Creek was filled in to become Water Street—both areas that frequently flood today. A half of a century later, Mayor Robert Young Hayne proposed a plan “to drain the city,” and an 1878 map shows the location of eight tidal drains installed at locations where drainage and flooding are still problems today. Water, it seems, flows where it’s destined to flow, impervious to time and the engineering wizardry of those who wish it could be channelled elsewhere.

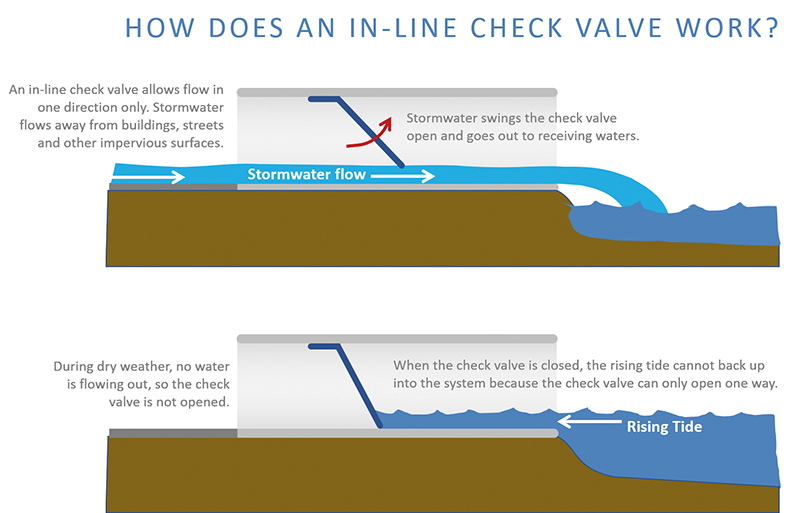

Charleston’s most recent stormwater management plan dates back to 1984. Since then, as the 14 different drainage studies and $238-million worth of infrastructure projects—including replacing old brick tunnels with 10-foot-wide drainage tunnels under Market Street—demonstrate, the city’s primary strategy has been to manage flooding by draining and containing, digging tunnels and shafts to pump or route water away from problem areas into rivers or other retention areas. This may not be enough given the “new normal,” Lindsey and others suggest.

At the same time, knowing what this “new normal” will look like is a bit like peering into Colonial Lake after a big storm—murky at best. In February of this year, Mark Wilbert, Charleston’s first-ever Chief Resiliency Officer, and his team released a revision of the city’s Flooding and Sea Level Rise Strategy, first published in 2015. The earlier document recommended the city plan for a 1.5 to 2.5-foot elevation increase for new facilities and infrastructure to protect against sea level rise over 50 years. The updated plan ramps that target up to two to three feet over the next half-century.

The newer version is more robust and perhaps more sobering. “Reinvest, Respond, and Readiness” were outlined as the three Rs of resiliency in round one, while the 2019 plan dives considerably deeper, enumerating multi-departmental initiatives around five critical areas: infrastructure, governance, resources, land use, and outreach. “At the core of it all is the common goal—to weave resilience into everything that we can,” the report states. Meanwhile, the tides continue to rise, the rains continue to fall, roads continue to flood.

“A lot of the problems we have today are due to things that were put in place long before we knew we had problems,” says Wilbert. He is referring to infill areas, as well as to inadequate pumping infrastructure. Add the crush of new development plus expanded roadways with more impervious surfaces, and the stormwater volumes quickly compound. “It’s 2019, and this is not okay anymore,” he says. “We need to adapt to massive changes (environmentally and in our built landscape) while also planning for the future, including needs like affordable housing. That means building in places and in ways that make sense.”

Wilbert and team have added a new color-coded “tracker” on the City’s Resiliency web page, which at quick glance resembles a game of Twister—all reds, yellows, greens, and blues. The chart is an effort to keep citizens informed of priorities within the five “critical categories” and updating them on what has been done. The enormity of the challenge is evident by the fact that reds and yellows (“Not Started” and “Started”) far outnumber the lonely blues (“Completed” items, which mostly involve the hiring of additional city staff) and greens (“Ongoing”).

Big tasks slated to begin this year include an “All Hazards Vulnerability and Risk Assessment,” which basically consolidates risks like sea level rise along with extreme precipitation and extreme heat, and a FEMA-funded Hazard Mitigation Plan, that will identify specific actions the City can take to help reduce or eliminate long-term risks. In other words, it all amounts to a flood of studies and countless hours of documentation.

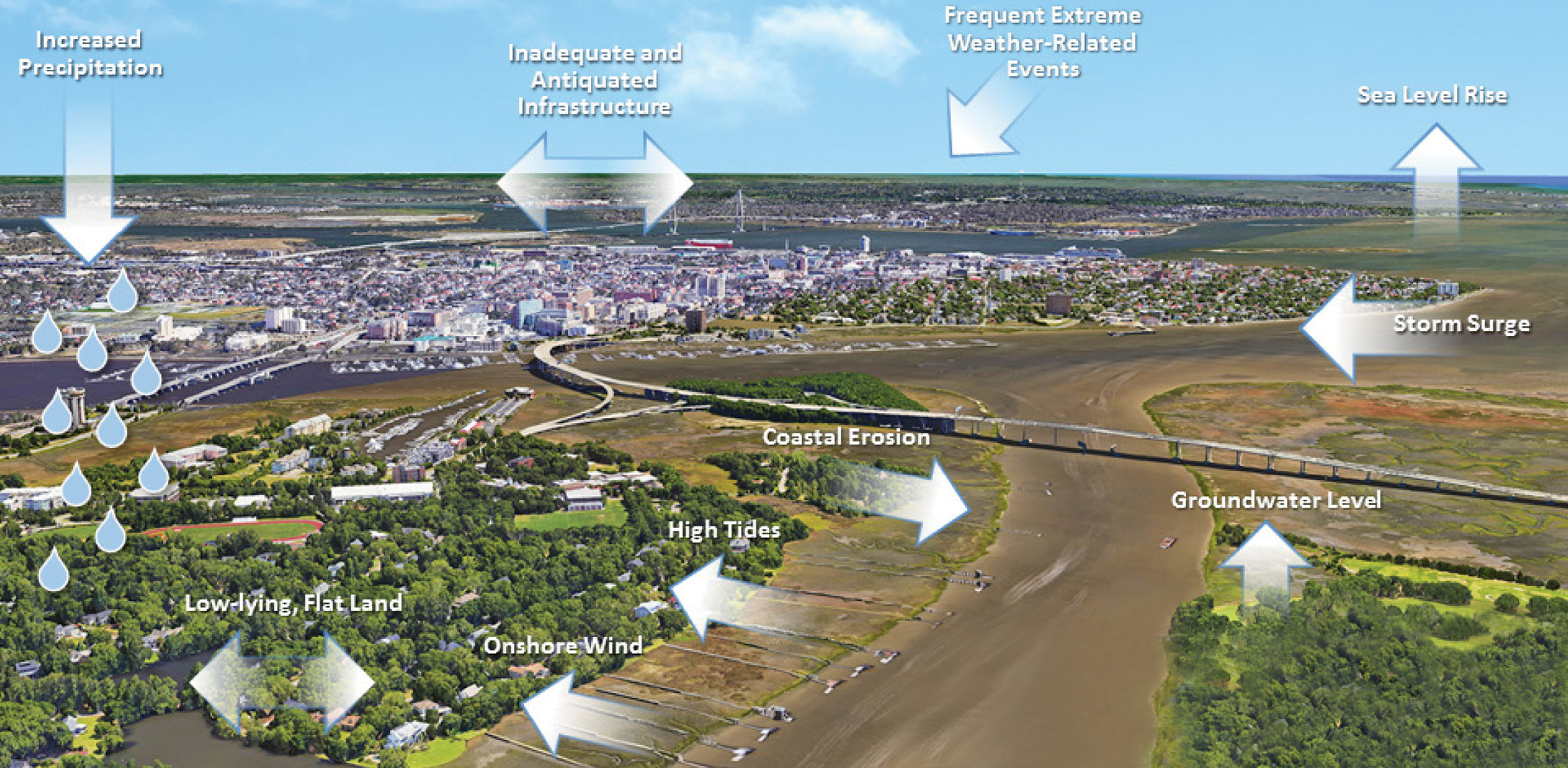

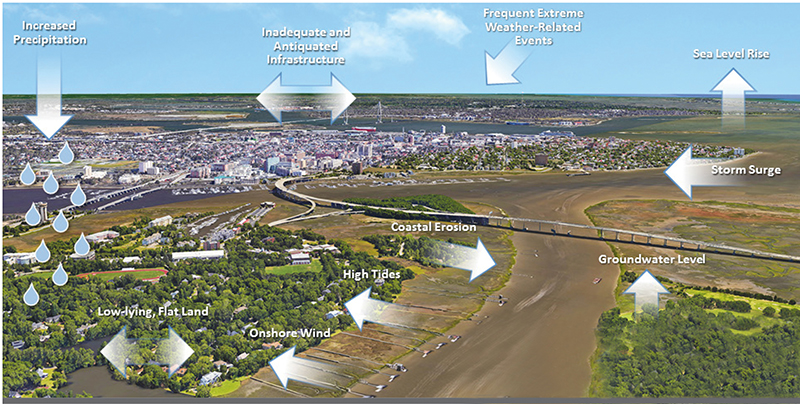

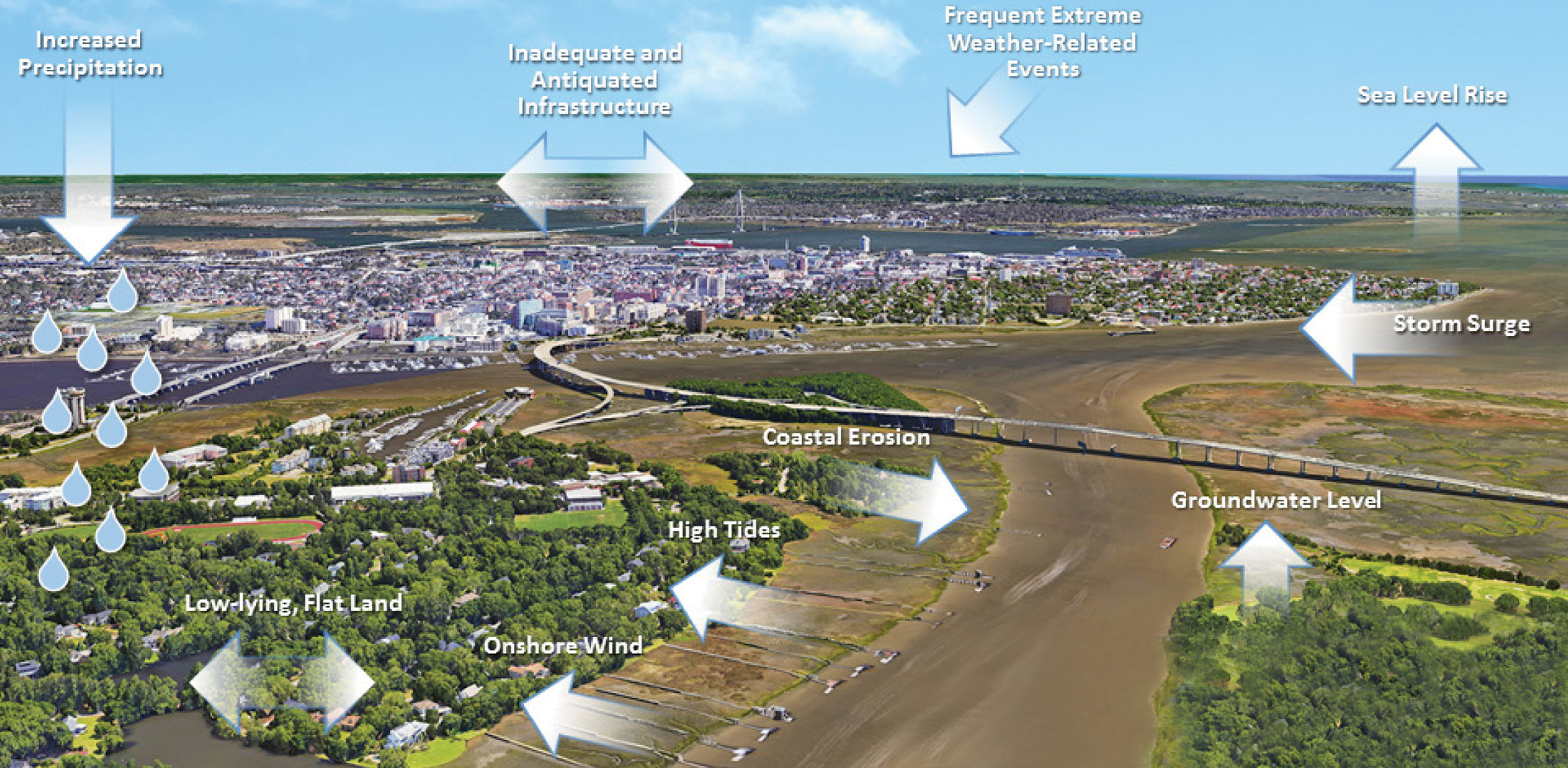

A Flood of Factors: This diagram, courtesy of the City’s 2019 Flooding and Sea Level Rise Strategy plan, shows the various and often interrelated factors that can result in flooding events.

Understanding the Problem

We also need to better comprehend the five different ways water impacts the city, suggests Lindsey. “Everyone, including the mayor, understands that addressing flooding is job number one, and the first step is to fill knowledge gaps about how the various types of water and watersheds function.” It’s more than a rainwater issue, he notes. We have groundwater, river systems, rain, tides, and storm surge—and these water sources interact differently depending on the specific borough or area being addressed.

Some of this research and analysis is underway. The Charleston Resilience Network, a consortium of public and private agencies and nonprofits all engaged in climate change issues, has started work on a vulnerability analysis, funded by a NOAA Regional Coastal Resilience Grant, that will develop localized flooding models that incorporate tides, meteorological events, wind, surge, and infrastructure such as tunnels and drains. The Army Corps of Engineers has recently begun a $3-million, three-year assessment of the peninsula to better understand the nexus of challenges. “It’s complex and nuanced, and requires a special technical expertise,” Lindsey says.

And who better to provide that additional expertise than the Dutch—a country of 17 million people who live at or below sea level.

Last summer, Wilbert, Lindsey, Mayor Tecklenburg, City Council members Mike Seekings and William Dudley Gregorie, and others, including Winslow Hastie of Historic Charleston Foundation, traveled to Amsterdam to see firsthand the innovative ways the Dutch are managing water issues. For one, notes Lindsey, they track real-time groundwater data to gauge rainwater impacts. “They have a fuller understanding of the problem and a completely different conception of their relationship with nature and water,” Lindsey suggests. “The Dutch have engineered and managed all aspects of their ecosystem in order to better live with water. It goes far beyond the thinking that says, ‘There’s storm surge out there; let’s keep it from getting in here.’”

The trip to Holland was an extension of conversations begun with Dutch water experts in March 2018, when the Charleston Resilience Network invited Dutch Ambassador Henne Schuwer to speak in Charleston and share insights from his country’s experiences and expertise. In his Dock Street Theatre talk, “Living with Water: Dutch Approaches and Charleston’s Future,” Schuwer noted that like Charlestonians, the Dutch have been dealing with flooding for centuries (their governmental water management agency, The Water Board, dates to 1222).

When a devastating 1953 flood in Amsterdam killed 1,836 people, they embarked on a more aggressive and innovative engineering effort. Then in the 1990s, the Dutch began to shift their paradigm from a “keep the water out” approach of building traditional defenses like dykes and dams, to a more adaptive (and trademarked) approach they call “Living with Water.™”

Multipurpose Solutions

“The Dutch speak about and address water issues in a straightforward way, there’s no jargon. It’s part of their culture to deal with water with 100 percent of governmental support and resources,” says Lindsey, who points out an obvious difference from what he says is our underfunded and “siloed approach”—something that Mayor Tecklenburg’s administration is working to change. (Responsibility for stormwater management used to fall under the Public Service Department, but it is now a separate Stormwater Department, with an $11.3-million budget dedicated solely to drainage and flooding issues.)

For Lindsey, one major takeaway from observing Holland’s methods is that “water solutions don’t have to be mystifying.” In fact, they can be inspiring and creative. Take, for example, the way the Dutch both protected and enhanced the beachfront in the North Sea town of Katwijk. To protect the beach and municipality from storm surge and future sea level rise, they engineered a series of man-made dunes rising to 25 feet above sea level and incorporated parking for nearly 700 cars underneath. Now people have more convenient access to a more protected beach.

Or there’s the new playground in South Amsterdam placed inside a landscape depression area lined with gravel and surrounded by bioretention strips. The playground does double-duty as a place for families to frolic and for stormwater to collect and attenuate.

“Single-purpose infrastructure is an inefficient way to use resources,” says Dale Morris, former economic advisor to the Dutch Embassy and director of strategic partnerships for the Water Institute of the Gulf. Morris and New Orleans-based architect David Waggonner of Waggonner & Ball are cofounders of The Dutch Dialogues, which consults with other municipalities, including Charleston, on Dutch-inspired water management strategies. Historic Charleston Foundation is lead partner in an initiative with the City of Charleston and other key stakeholders to engage Morris and team to evaluate and propose opportunities here for similarly innovative, multipurpose water management strategies, an effort that kicked off with a two-day scouting visit here in January and a follow-up visit in March.

“Why just build a sea wall when you could build one with a promenade on top, or a dam that doubles as a road and pedestrian/bike path? The city and county are allocating tax dollars every single day—there’s already a $200-million drainage improvement effort underway—so the question is how to give citizens more bang for their buck,” says Morris. “Our goal is to show people that a more holistic way of thinking is possible, and to give ideas for capital improvement projects that are attractive, multipurpose, and enhance quality of life beyond just drainage.”

Going Up, Going Green

Will the Dutch formula really move the needle in Charleston? Winslow Hastie, president and CEO of Historic Charleston Foundation, has both heard and asked himself this question. Hastie and his staff have been at the forefront fielding flood-related questions and complaints from homeowners of the city’s landmark historic properties. People have grown tired, he says, of ripping out HVAC systems ruined year after year by downtown flooding. “It’s not good for the integrity of these historic buildings, and it’s certainly not good for the homeowners,” he notes.

In the wake of Hurricane Matthew, the foundation was inundated with inquiries from homeowners about elevating historic structures, Hastie says. “If you had asked me four years ago if the preservation community would embrace elevating historic buildings, I would have said, ‘No way.’” But the foundation and the Preservation Society, along with the Board of Architectural Review, have all changed their tune. “There’s 100 percent consensus, which is almost unheard of. Adaptation is critical,” says Hastie, whose organization helped develop a new set of guidelines for lifting historic properties.

Following his trip to Holland and subsequent meetings, Hastie is no longer a skeptic. He believes that the Dutch formula can indeed offer positive adaptive solutions in Charleston. “The visit was completely eye-opening,” he says, particularly in terms of how living with water is “top of mind at every level of government.” The solutions are integrated at every scale, from individual homeowners using rain barrels and creating rain gardens, to huge infrastructure undertakings like the Maeslantkering storm-surge barrier (a massive gate-like sea wall), to the “Room for the River” projects that reclaim developed areas and return them to greenfields, restoring their natural role as floodplains—similar to proposals on tap for parts of West Ashley’s repeatedly flooding Church Creek basin.

“Living with water is a lens through which the Dutch look at everything, from land-use planning to infrastructure development,” Hastie says, an effort that requires intense and massive collaboration, he notes, with a hint of concern. “That’s a big challenge for Charleston, this question of how we can work together to tie our various initiatives into a single narrative with a cohesive strategy.”

Some of that collaboration has actually been going on quietly for years, decades even, from organizations like Audubon South Carolina and The Nature Conservancy, that this year celebrated a 50-year partnership in wetland conservation and restoration in South Carolina, dating from their 1969 success in protecting an initial 3,415 acres of wetlands around Four Holes Swamp. Today, 18,000 acres are protected in the Francis Beidler Forest, including Audubon South Carolina’s bird sanctuary.

“This type of green infrastructure, or nature-based solution, enables wetland systems and their upland buffers to collectively provide tremendous flood-storage capacity and water quality improvement, helping and protecting communities downstream,” says Sharon Richardson of Audubon South Carolina.

Planting trees both on the peninsula, as the city encourages citizens to do in its resiliency plan, and on a larger scale, such as the 215,000 native hardwood seedlings the Audubon team planted this past March, is another nature-based proven method of flood mitigation. “During a rainfall event of one inch, one acre of forest will release 750 gallons of runoff, while a parking lot will release 27,000 gallons,” Richardson adds. The Nature Conservancy has seen success in natural oyster reef restoration along the coast, another way to harness nature’s own resiliency mechanisms, improve water quality, and buffer against storm surge and sea level rise.

Cost/Benefit

Paying for innovative solutions is another challenge, note many civic leaders, as well as consultant Dale Morris, who admits being initially reticent to dive into a tax-averse environment (i.e. one like Charleston). He lacked confidence that proposed solutions would be funded in order to be implemented. After several visits to Charleston and with the initial Dutch Dialogues Charleston scouting visit complete, the level of interest their team discovered assures him. “There are a lot of initiatives already underway; our goal is to synthesize and build on that,” he says. “We are confident that the process will work.”

“The momentum on the ground in Charleston is fantastic,” adds Waggonner & Ball’s Janice Barnes, who consults with the Dutch Dialogues Charleston team. But the process and the solutions take time, she cautions: “It won’t be done by the next hurricane season.” The upside, she adds, extends beyond improved drainage and resilience to workforce opportunity and growth. “You have to integrate economic development into flood solutions,” she says.

In regions like Southern Louisiana, she points out, the Kresge Foundation has found the economic, business, and workforce impacts from water projects in the region measure in billions of dollars. Benefits include an estimated 12,000 new jobs in the water management sector over the next decade, nearly half of which will pay an average median salary of $53,000 a year. “In New Orleans, they’re seeing people transition from lower-paying hospitality industry jobs to higher-wage water management positions,” Barnes says. She anticipates a similar boon here. And then there are the savings that come from adequate preparation and protection. According to a 2017 study commissioned by the Federal government, every dollar invested in hazard mitigation saves the nation six dollars in future disaster costs.

But that still begs the question of where that initial dollar—or the $2 billion of them that Mayor Tecklenburg suggests is needed to solve flooding—will come from. “It’s like we’re operating in this parallel universe—we’re holding sessions, inviting experts from Europe to consult with us, but there seems to be a partial conspiracy of silence when discussing where the money is going to come from,” says Dana Beach, founding director of the Coastal Conservation League. Beach and a group of 10 or so concerned peninsula residents met with the mayor and Wilbert last fall to discuss efforts to address flooding. They requested a detailed project list of everything that needed to be done to achieve flood resiliency, as well as an associated expense estimate, but left empty-handed.

“Wilbert suggested it would ‘be alarming’ to people to see such a list,” Beach recalls. The upshot of the meeting however, was that the mayor’s one suggestion as to where the money might come from was the Accommodations Tax. “The problem is that’s only about $10 million, or five percent of the projected $2 billion needed. First of all that’s ludicrously low, and secondly, that money is already allocated,” he adds.

Meanwhile, experts agree that Charleston’s flooding issues are increasingly serious. And it’s clear that residents don’t need convincing. “But it’s not a time to be apocalyptic,” says Jacob Lindsey. “I am optimistic.” He’s observed a “real evolution in the city’s water awareness,” away from a mind-set of merely coping with flooding to one that is creatively finding multipurpose water management solutions. Along the way, he anticipates, Charleston will become greener and more resilient, and citizens will benefit from new amenities—maybe even playgrounds and parking like the Dutch developed.

But there is an urgency that some, including Dana Beach and City of Charleston Council member Mike Seekings, feel is not being taken seriously enough. Having accompanied the delegation to Holland and seen the Dutch approach firsthand, Seekings is all for the dialogues and partnership. “But we have an issue with talking too much, let’s take action,” he says, noting the numerous and often repetitive forums. “The Dutch aren’t afraid to try something and risk making a mistake. If it doesn’t work, they try something else. It’s in times of relative quiet and calm that we should be taking action, and we’re not,” says Seekings. “We know what our future looks like. We need to be dancing with that, and strategically choreographing our response to it.”

“The solutions aren’t all about sexy designs,” Lindsey adds. Rather, they require collaboration, technical expertise, and resources. The payoff, he suggests, is “smarter solutions that offer a better quality of life.”

-