Read about the opportunities she sees in the museum’s educational programming and how she’s navigating the challenges that lie ahead

A biomedical engineer might not be the most obvious choice to lead an international history museum, but Tonya Matthews has rarely pursued the obvious.

Not in preschool, when she pestered her mother until she taught her to read like the other kids—despite the fact that she was barely four and those other readers were a year or two older. Not in high school where she loved English, social studies, and writing but signed up for an extracurricular science and math program anyway, “because it meant I got to spend a week on a college campus by myself, no parents, no siblings—sold!” And not in college, where she was one of the few women, and even fewer Black women, enrolled in Duke University’s engineering program. (She also served as an editor for the campus newspaper, even though some folks think “engineers don’t write.”) Or in graduate school, where she performed spoken-word poetry in Baltimore coffeehouses by night, while earning her doctorate in biomedical engineering at Johns Hopkins by day.

“I’ve come to realize that two of the scariest words in the English language are ‘racism’ and ‘algebra.’ I happen to do both.” —Tonya Matthews, PhD

No, none of it obvious or expected, but all of it a beautiful integration of right brain, left brain; engineer and poet; CEO and storyteller; STEM champion and diversity advocate; history lover, and now, history maker, as Dr. Tonya Matthews takes on the most exciting and challenging role of her career to date, as the chief executive officer of the International African American Museum (IAAM).

“I’ve come to realize that two of the scariest words in the English language are ‘racism’ and ‘algebra.’ I happen to do both,” says Matthews. Whether solving for an unknown factor or confronting a long-standing injustice, Matthews understands how both algebra and racism can make people feel fearful, uncertain, and intimidated. “When I stepped in this role, I recognized the energy of the conversations I was having. As an African American female professional, I’m always on message in these spaces, in these difficult conversations,” she says. “But I also know the bottom line is you cannot educate through fear. So we must always be conscious and empathetic to the fear and consciously pick away at it so we can get the education going.”

In bringing to life the decades-long dream of a museum dedicated to telling the stories of the African American experience, from the pre-Colonial era to present day, Matthews is committed to removing that fear. Perhaps it’s not happenstance that the etymology of “algebra” comes from the Arabic, “the reunion of broken parts” or the healing of a fracture. The math-loving engineer CEO may be on to something: Racism and algebra are both equations seeking the same variable, healing and reuniting.

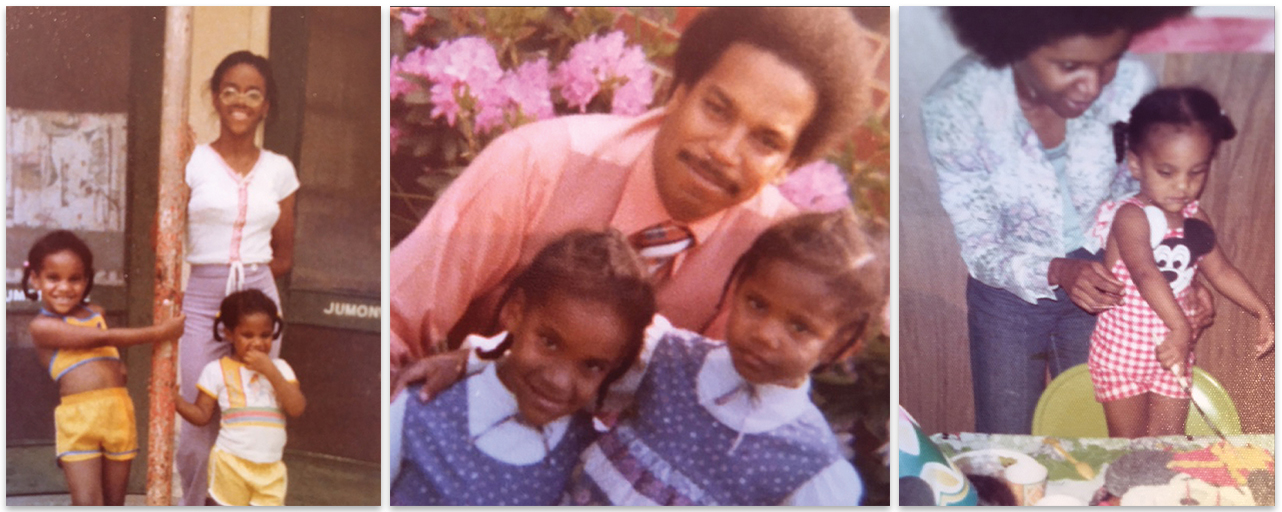

While a master at linear equations, Matthews’s path to Charleston, where she landed in April 2021, has been far from linear. It began outside of Washington, DC, where she and her three younger siblings and her parents—her father a police officer and her mother an educator—lived in a supportive, middle-class neighborhood in the predominantly Black Prince George’s County, Maryland. “My family believed education was the way through and forward. It was the way we would help teach everyone that Black folks are not just what you see on TV,” says Matthews, an unapologetic, curious “geek” who thrived in that environment. “I loved school and school loved me,” she says.

With a competitive nature and reputation—true to those early-reading preschool days—for “punching above my weight,” Matthews excelled. Her initial plans to become a doctor “and save the world” shifted after attending that George Washington University program, where she realized that technology and engineering were tools that could be harnessed to help doctors and others. She graduated as valedictorian and enrolled in Duke’s biomedical and electrical engineering programs, where she found the challenges less intellectual than cultural.

“I was well prepared academically, and I knew it,” Matthews says, “but I wasn’t prepared for an environment where I was confronted with faculty and students who were not convinced I belonged there and had the audacity to say so.” In 1992, Duke’s undergraduate student body was 11 percent minority, and even lower in the engineering school. “Duke was my first of many awakenings,” says Matthews. “The illusions of earned exceptionalism and earned privilege meant that they didn’t have to accept that folks like me belonged or were a ‘new norm.’ I was so clearly off-brand.” She quickly learned to lean into difficult conversations and network across cultural lines, proving herself time and again, as dorm president and as an outspoken columnist “raging against the machine, like every 19-year-old,” she says.

Raised in a predominantly Black, middle-class community outside of Washington, DC, Matthews was the oldest of four in a tight-knit family that prioritized education as “the way through and forward.” (Pictured from left to right) Shown with her older cousin Felicia and Rochelle in New Orleans, where her mother’s family is from; Matthews’s father, Tim, was a police officer, shown here with Matthews and her sister Rochelle, who’s 13 months younger; Matthews’s mother, Eileen, an educator and administrator, helps a young Tonya (and Mickey Mouse fan) cut her birthday cake.

After earning her PhD (a dissertation on inner-ear hair cells, hinting at her good listening skills), Matthews worked at the Maryland Science Center and briefly at the Food and Drug Administration, before being appointed vice president for museums at the Cincinnati Science Center, a consortium of three museums where Matthews honed her leadership skills and launched a Girls in Real Life Sciences (GIRLS) program. “There, I began to fully appreciate the role of museums as anchor institutions in the educational ecosystem,” she says. “It also taught me the nuts and bolts of being an executive and the power and pull of vision.”

When she got the call in 2013 to become president and CEO of the Michigan Science Center, “I was given room to fire on all cylinders,” says Matthews. In Detroit, she discovered both a museum and a community in the process of rebuilding. “It was as if the entire community was a start-up company. There was a true entrepreneurial spirit and a sense that any idea is a good idea as long as we haven’t tried it before,” she says. “We were building a science center all about innovation, which was serving a critical need. Personally, it was my own proof of concept reckoning on the power of setting vision.”

In 2015, she created The STEMinista Project (“catching a theme?” she laughs) and earned national recognition for initiatives to engage girls in sciences. After six years in Detroit, she joined Wayne State University as associate provost for diversity and inclusion, a role that came naturally to her. “As a Black female professional in whatever space you’re in, you’re a de facto diversity officer,” she says.

Matthews became CEO of the Michigan Science Center in 2013, where she rebuilt and rebranded the institution following a period of closure during Detroit’s economic downturn. “The whole city was like a start-up,” she says; (From left to right) The Michigan Science Center tornado exhibit; In 2015, Matthews created The STEMinista Project, an initiative that inspires middle school girls to consider careers in science, technology, engineering, and math; the Mars Rover exhibit

“Most times, I’m quite the type A person who plans for everything. But as a kid I never planned on being an engineer, and as young adult, I never planned on working in museums,” she says. “I suppose I’m ultimately more driven by my ‘why,’ than my ‘how.’” In reflecting on her unexpected path, Matthews recalls being on a personal retreat and writing in a vision notebook that she longed to find a position where both sides of her, right brain and left brain, heart and mind, were valued and engaged. “I didn’t want to always feel like I was competing with myself, but instead that I could be the tactical, strategic problem solver—the one who wields a spreadsheet like nobody’s business—and also the poet and storyteller, the one who can inspire and motivate,” she recalls. Detroit filled that bill, and now, so does Charleston. “Yeah, be careful what you wish for,” she laughs, “and for the love of Pete, don’t write it down!”

Joking aside, Matthews is more than energized by the opportunities and challenges she’s finding at the helm of the IAAM. Her journey here has been winding, as has the museum’s. After its inception more than 20 years ago by then Mayor Joe Riley, it has taken nearly that long to raise the $75 million in capital funds to build the building (so far more than $100 million has been raised, and the building envelope is complete). During this period, the site for the museum shifted from its initial location across from the South Carolina Aquarium to Gadsden’s Wharf. Among the more than 40 percent of captive Africans who landed in the US through Charleston, a great many took their first steps onto Gadsden’s Wharf.

One CEO has come and gone, while Dr. Bernard Powers, the interim CEO prior to Matthew’s appointment, remains on the board and actively involved. Other board members and staff, including the founding director of education and engagement and its chief curator, have also moved on during the long preamble to the museum’s anticipated opening late this year.

Many say the turnover is partly par for the course for projects of this magnitude. Others suggest it is partly indicative of a fraught period, one of tension with community groups and concerns voiced by staff regarding the organization’s vision and inclusivity. A group called Citizens Want Excellence that includes Dr. Millicent Brown—a Charleston native, retired professor, and community activist—and others has pushed for more local voices, especially African American voices, to be included in the organization’s decision-making and planning. In December 2021, Bernice Chu, the IAAM’s former director of planning and operations, sent a formal memo to the board outlining a number of serious concerns. “It has hemorrhaged prominent Black scholars and professionals and is becoming a known racist and misogynistic organization,” Chu wrote, as reported in the Post and Courier. The board is reviewing her allegations. Powers and others acknowledge that the start-up process has been challenging, but not unexpected given the museum’s subject matter.

Matthews is undaunted. “I prefer roles that have a learning curve,” she says. “To be leading an organization committed to trying to centralize the African American voice, to center it in a history museum, and to be doing this in South Carolina, in the Lowcountry, in Charleston—a community that is clawing its way to a new conversation about its relationship to racism and its supporting power structures, a community with unique and deeply rooted blind spots as we grapple with these conversations—I knew this would be challenging. My learning curve entails understanding what our blind spots are, how we talk about racism here, and how we don’t—and how that relates to the dos and don’ts of such conversations all over the country,” she adds. “All of my roads have led me to this, and I’m far more prepared than I would have ever imagined.”

Charleston’s IAAM will feature visiting exhibitions as well as permanent galleries and collections “telling the untold stories of the African American journey.” (Clockwise from top) A rendering of the Gullah Geechee exhibit, which will feature a replica of the Moving Star Praise House, built on John’s Island in 1917, as well as the photo More Scaly Specimens by Frank G. Tarbox, of Gullah fisherman was taken on a narrow strip of land between Mosquito Creek and Winyah Bay on South Island, near Georgetown, South Carolina. The fishing village was discovered in 2017, when human remains were found in the eroding shoreline after Hurricane Irma.

Rita Scott, former vice president and general manager of Live 5 News WSCS-TV, served on the initial board of the IAAM and has rejoined with new enthusiasm after Matthews’s appointment. “Seeing what had been planned in the beginning and what is here today, it feels like it’s been divinely guided,” Scott says. “The fact that Gadsden’s Wharf became available truly makes this sacred ground. All of us have learned a lot about telling stories of pain and suffering but also of hope and possibilities to truly build a community based in love. You’re going to have ups and downs and some who don’t like exactly what they think is coming, but all of this has been built with a commitment to tell this story accurately, with the force it needs to be told. That has taken a lot of time and effort. But we definitely found someone up to the challenge.”

According to Kitty Robinson, former CEO of Historic Charleston Foundation and an IAAM board member who served on the search committee, Matthews is “the right person at the right time. She’s a far-reaching visionary with the breadth, width, and depth of skills we need. But mostly she’s so warm and truly interested in others, in getting to know the community with whom and for whom she’s working. She searches for truth, and she finds it and tells it.”

Searching for truth, noticing blind spots, mastering the learning curves—it’s all part of the algebraic equation that Tonya Matthews is tackling as she prepares for the IAAM’s opening in late 2022. No official date has yet been announced, but Matthews and her board are confident, with the building now complete and exhibition plans well underway, that all is on track. One of the museum components Matthews is most excited about is the Center for Family History. “I was curious as to how the IAAM was so bold as to incorporate a first-class genealogy center in our plans, then I got to South Carolina and realized you can’t have a conversation without hearing about someone’s great-grandfather or great-great-grandmother—it’s part of the culture here. So it makes perfect sense to have echoes of that in this space,” she says.

However, she also notes a “disconnect” when people talk about their great-great-grandparents “but have no concept about the structures and systems operating in the world in which their ancestors lived,” she adds. “Our opportunity is to leverage these strong connections to this past, to these ancestors and get to some authentic storytelling about those eras and challenges and how they impact us today.” That disconnect, she believes, is best addressed by practicing radical empathy.

“As someone who has had her identity challenged in one way or another her entire life, it’s impossible for me to ignore how the retelling of these stories will challenge others’ sense of their identity over generations,” Matthews says. “I know what that feels like; I’m not going in blindly or unkindly. I may not know the way forward yet, but this is the conversation this museum will be having with the country. So,” she adds, “let’s buckle up.”

Get a visual tour of the plans for the International African American Museum and hear Walter Hood, founer of Hood Design Studio, describe the design of the Africaan Ancestors Memorial Garden at https://iaamuseum.org/museum/.

Listen as Dr. Matthews describes The STEMinista Project at Michigan Science Center:

Watch Tonya M. Matthews’s TEDxCincinnati talk on spoken-soul poetry and the perception of sound:

Styling by Lisa Jean Walsh; rendering courtesy of IAAM; photographs courtesy of JA Moore, Dr. Tonya Matthews, Cincinnati Museum Center, Michigan Science Center, & @steminista.project