December 2022

When New York philanthropists Victor and Marjorie Nott Morawetz decided to find a winter home in 1929, they had the means to move anywhere in the world. But the ultra-wealthy couple, who dined with the Vanderbilts and spent weekends with the Roosevelts, chose Charleston. It was the beginning of a mutual love story that spanned more than 30 years. And while their names are all but forgotten, their legacy of art, architecture, and natural beauty surrounds us to this day

Written By Suzannah Smith Miles

Victor and Marjorie Nott Morawetz arrived during the Charleston Renaissance of the late 1920s. It was an exciting period when the city was alive with exceptional artists, including painters Alfred Hutty, Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, Anna Heyward Taylor, Edwin Harleston, Prentiss Taylor, and Elizabeth O’Neill Verner and writers Josephine Pinckney, Hervey Allen, John Bennett, Julia Peterkin, and Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Intellectually, Charleston was experiencing a dazzling period of enlightenment; Physically, it resembled the “Catfish Row” set in Dubose Heyward’s Porgy and Bess. The city was broke, as were most of the residents. The combination of time and poverty had transformed the former antebellum grandeur into what one wit wryly termed “ramshackled elegance.” As New York artist and lithographer Prentiss Taylor wrote, “The decay is too, too divine.”

Yet paucity had not dimmed the city’s innate joie de vivre. Behind the faded shutters and peeling paint was a continued whirl of cocktails, culture, and conversation. The Morawetzes stepped effortlessly onto this stage. Victor, described as a dapper gentleman, a “rare man” of courtly manner and broad culture, and Marjorie, who had the ability to be both “dignified and fun,” were immediately accepted for their brilliance, generosity, and, before long, their commitment to early preservation efforts. They would become instrumental in saving some of the area’s historic buildings, most notably the legendary Pink House on Chalmers Street and Fenwick Hall (also known as “Fenwick Castle”) on John’s Island.

Having immense wealth helped, of course. Victor retired at the age of 51 after a sterling legal career. The Baltimore native had graduated early from Harvard, written his first book on contract law at age 23, and from his Wall Street law firm, provided legal counsel to the great financial barons Andrew Carnegie and J. P. Morgan. In addition, his work as chairman of the board of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway helped him amass a tidy fortune.

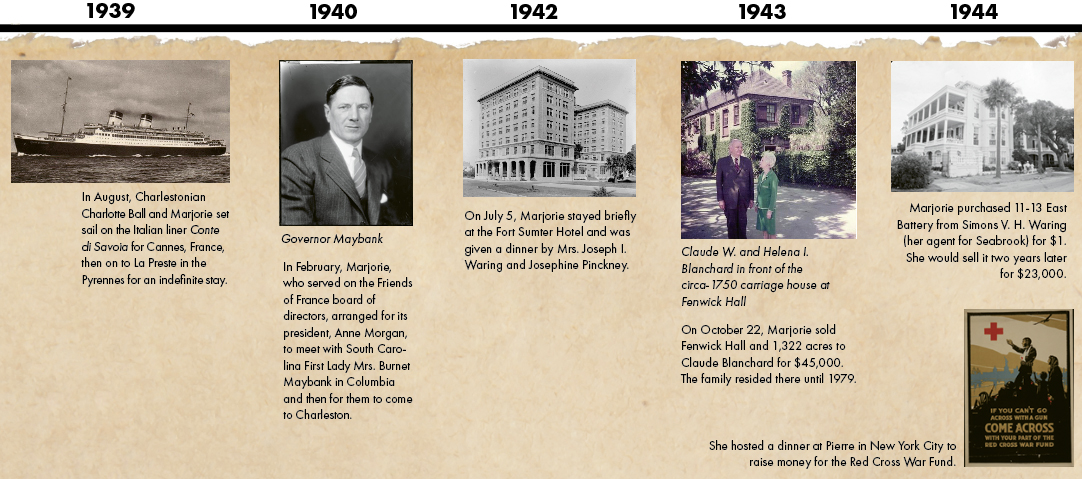

After the death of his first wife, Violet Westcott, in 1918, Victor met the engaging young Washington sophisticate Marjorie Nott, daughter of Chief Justice Charles C. Nott. It was a May-December relationship but an ideal pairing of intelligent personalities. Both had traveled extensively in Europe and shared a passion for the arts. They married in 1924 and moved into a home in Manhattan. Victor had just sold his 100-acre Long Island estate (complete with a 32-room mansion and sunken gardens) to his friend Andrew Mellon. The couple was now searching for a warmer climate to spend their winters.

They may have selected Charleston—and been accepted so easily by the town’s notoriously closed upper crust—because of their relationship with one of its most illustrious clubs, The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals. Formed in 1922 by members of the Lowcountry elite, the choral group aimed to preserve the religious songs of the formerly enslaved and generate revenue to assist the Gullah people. Marjorie saw the society perform in Boston in 1928 and was so enthralled she brought them to New York the following year to sing for the prestigious Thursday Evening Club.

The connection may also have been made through Charleston attorney Alfred Huger, who was president of the society at the time. After graduating from Cornell, he had worked for a Wall Street law firm, marrying the socialite daughter of the firm’s principle. In addition to being business colleagues, Huger and Morawetz traveled in the same social circles. Yet connections weren’t the only reason Charleston opened its doors to the couple: Put simply, they were delightful people with a genuine affection and enthusiasm for the city they adopted as their own.

The Pink House

It was largely through their close friendship with local author Josephine Pinckney that the Morawetzes took on the task of restoring the then-crumbling Pink House. At this time, many Holy City dwellings were derelict, not able to be fixed because of the depressed economy. Pinckney, with the guidance of noted architect Albert Simons, had restored her home at 36 Chalmers and transformed it into one of the city’s most charming residences, where the Morawetzes were frequent guests at her celebrated cocktail buffets.

The Pink House, a former 18th-century tavern thought to be the oldest building on the peninsula, was only a cobblestoned block away. In May 1930, the couple reached into their deep pockets, bought the tiny two-story dwelling built of salmon-hued Bermuda stone, and put Simons in charge of its rehabilitation.

Since the plan was for the Morawetzes to use it for entertaining, a small addition for a kitchen and bath was built to accommodate caterers. Eventually the couple offered it as a retreat for struggling artists like Taylor, who worked there in the 1930s. It later served as a studio for Alice Ravenel Huger Smith. Marjorie owned the Pink House until 1946, when it was sold to writer Harry McInvaill Jr. and his wife, the poet Talulah Lemmon.

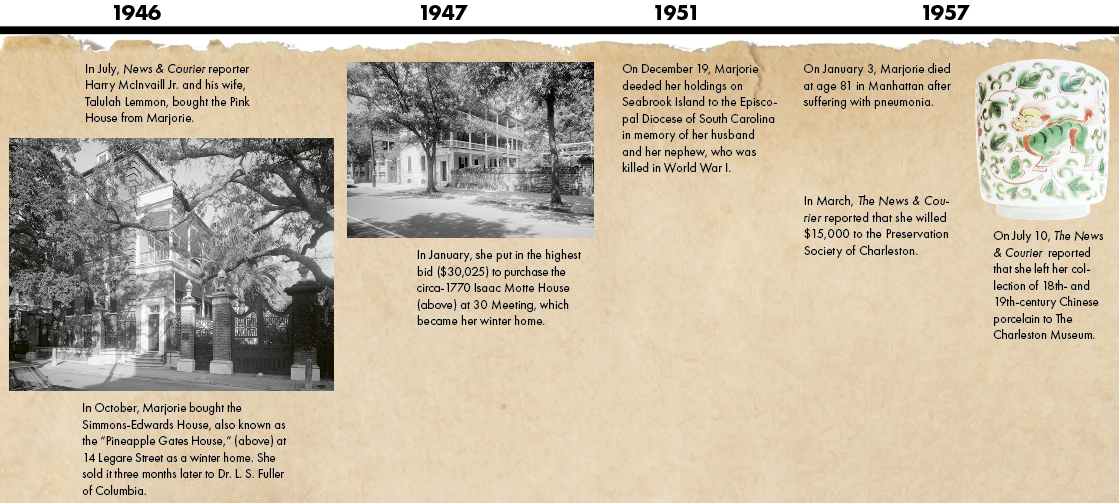

“The greatest asset of Charleston at the present time consists in the beauty of its location and its ancient houses,” noted Victor in a 1931 News & Courier interview. “The people should do everything possible to preserve the old houses and the character of the place, which is unique.” And he put his money on his word. The Pink House was only one of many historic structures restored under the Morawetz aegis. The properties they purchased—some mainly to be stabilized before a permanent owner was found—include 46 King (bought in 1929), used as their residence while work was being done at Fenwick Hall; the Ravenel Mansion at 11-13 East Battery (1944); the Simmons-Edwards House with its famed pineapple gates at 14 Legare (1946); and the stately Young-Motte House at 30 Meeting (1947), Marjorie’s last winter residence.

Fenwick Hall

Perhaps the couple’s most massive undertaking was the restoration of John’s Island’s Fenwick Hall, which was little more than a shell when Victor purchased the estate in 1930. “We were attracted to Fenwick Hall when we first saw it,” Victor told The News & Courier as renovations began on the Georgian manor house. “In fact, we were attracted by Charleston and its beautiful houses. The people of Charleston have a degree of cultivation and charm, which we do not find elsewhere in the world.”

Unlike other Northerners who purchased plantations for winter hunting retreats, the Morawetzes focused their attention on saving an architectural treasure. “I did not come here to shoot,” said Victor. “We will endeavor to restore Fenwick Hall as much as possible to its original condition and to make it a home.”

Restoring the two-story brick mansion, built by John Fenwick circa 1730 on the Stono River, was an immense project. Under the guidance of Simons and building engineer C. Stuart Dawson, every means was taken to ensure the historical integrity of the structure—all 13 rooms, five baths, and seven bedrooms. Original hand-carved pine and cypress moldings remained intact while electricity, modern plumbing, a kitchen wing, and pool house were added. The original fireplaces were repaired, including one in the drawing room purportedly haunted by a ghost.

The deep basement held an oil furnace, auxiliary kitchen, wine cellar, and servants’ quarters. One unusual feature was an underground passage that, according to legend, was an escape route to the Stono River. The late Charleston historian Samuel G. Stoney quelled these stories while the house was being renovated, quipping to The News & Courier that “fancy has outrun fact.” The truth, said Stoney, was that it was merely “a serviceably large drain, through which a not too large boy might creep without great discomfort to dislodge the carcass of a cat.”

One of the most impressive additions was the saltwater swimming pool with water pumped in from the Stono River, first to a purification system and then to a heating system for warming to a desired temperature. The pool house was set amid several acres of gardens noted for stands of camellias, azaleas, and live oaks. It was also on these grounds that Victor created a place to indulge his passion for cactus.

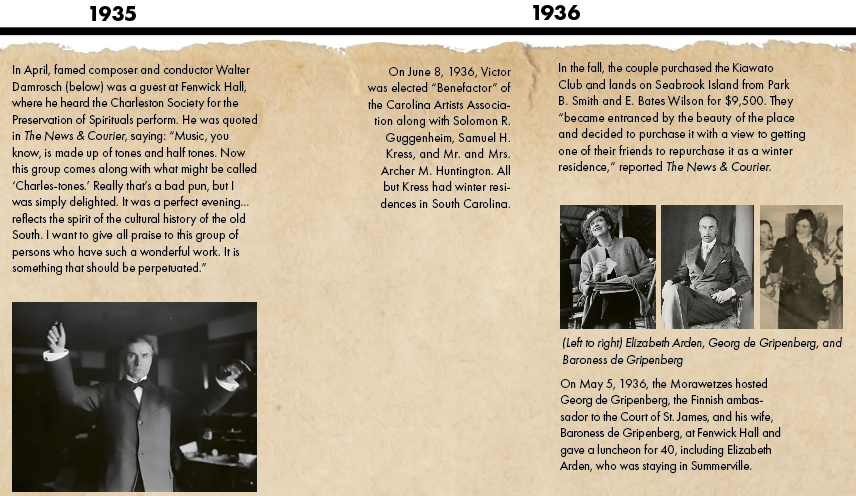

The Cactus Garden

A horticulture hobbyist, Victor had a fascination with cacti and may have been the foremost collector of them in the world at the time. He traveled regularly to obtain specimens and had them delivered by rail from the Southwest. Wrote The News & Courier in 1939, “Some of these giants are more than 1,000 years old…. he had scores of varieties, some of which bloom only at night. The cactus garden was one of the sights shown to visitors to the place, which had become famous for the hospitality of its owners.”

In truth, it was only because of Victor’s unlimited means that the garden thrived. The humid climate was totally unsuitable for cacti, which prefer arid conditions. Thus, they had to be continually replaced. Still, in its heyday, the garden was a matchless, if not unusual, centerpiece of the Fenwick Hall grounds.

Victor’s love of plants tendriled into other areas. He was a friend and backer of Prince Matchabelli, the perfume maker, and at one time suggested that Charleston would be a good place to raise shrubs, flowers, and other plants for his essential oils. While that idea never came to fruition, another outstanding endeavor did. As early as 1931, Victor had bemoaned the lack of trees along the highways leading into town. He suggested that some organization might begin a movement to line the roads with magnolias. In 1935, Victor took on the task himself and had 200 planted along Maybank Highway where it runs through the municipal golf course. “He wished to assure an avenue of loveliness for all who pass that way,” wrote The News & Courier in 1938. The magnolias are still there—beautiful reminders of one man’s determination to better the Lowcountry surroundings.

Seabrook Island

In 1937, the Morawetzes turned their attention to the “wooded oceanfront paradise” called Seabrook Island. Almost entirely undeveloped at the time, the majority of the land was owned by the Andell family, who was selling 560 acres of the southern portion. Entranced by the island’s natural beauty and concerned that it would fall victim to timbering, the Morawetzes not only purchased the Andell lands but also the defunct Kiawato Boys’ Club tract, eventually renovating the clubhouse into their summer cottage. They also purchased the 247-acre Jenkins Point tract on the North Edisto River. The couple leased the land (today’s Camp St. Christopher) to the Episcopal Diocese of South Carolina for only one penny a year so that it could serve as a summer retreat for boys.

Sadly, Victor only had a brief time to enjoy Seabrook. He died of a heart attack at the age of 81 in 1938. Yet with typical generosity, he left a codicil in his will that after Marjorie’s death, the Seabrook property would go to the Episcopal Church. Marjorie spent summers at Seabrook for the remainder of her life, and the beach cottage was happily inhabited by houseguests from the world over. In keeping with Victor’s wishes, when she died in 1957, the church was deeded the land. While the diocese subsequently sold most of the property, the Camp St. Christopher grounds remain as a retreat for children and adults.

A Lasting Legacy

The couple’s contributions stretched well beyond saving historic properties, planting gardens, and conserving natural vistas. Both were patrons and members of the board of directors of a number of important civic organizations. For her part, as early as 1932, Marjorie worked with the Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings (today’s Preservation Society of Charleston) to raise funds for the restoration of the Joseph Manigault House on Meeting Street. Likewise, in 1937, along with Josephine Pinckney, Dubose Heyward, and others, she and Victor were patrons of the Committee for the Dock Street Theatre, which worked to save the historic venue, the first of its kind in America.

Victor’s contributions to the Carolina Art Association and Gibbes Art Gallery earned him the title of “benefactor.” In 1936, he donated two paintings by Washington Allston, Moses and the Serpent and David Playing Before Saul, along with a self-portrait by Lowcountry artist James DeVeaux and a miniature of Mrs. Samuel Wilson (née Paul) by Thomas S. Officer. The following year, Victor presented the gallery with a gift of 18th- and 19th-century miniatures, generally portraits done in watercolor on thin sheets of ivory. Seventeen in total, these included works by noted Charleston artists Charles Fraser and Henry Bounetheau. When combined with those already in the gallery’s possession, they created a collection that today is considered one of the most prestigious portrait miniature collections in the United States.

In 1937, the Morawetzes gave $75,000 to Roper Hospital to build a wing dedicated to the treatment of African Americans with contagious diseases. They also gave substantial monies for a maternal welfare clinic and in his will, Victor left more than $1 million to the Medical Society of South Carolina.

Marjorie lived almost 20 years after Victor, returning to Charleston annually to spend time with friends she’d made in the town she’d grown to call her own. She continued her work for the community, serving on the board of the Charleston County Association for the Blind, and with the onset of World War II, on the boards of the Red Cross War Fund and Friends of France, arranging for the latter group’s president to speak in New York, Columbia, and Charleston. She left a bequest of $15,000 to the Preservation Society and gave her outstanding collection of 18th- and 19th-century Chinese porcelain to The Charleston Museum.

After Marjorie’s death in 1957, Albert Simons wrote a letter to the editor of The News & Courier that sums up the love and respect Charlestonians had for the Morawetzes, noting, “Their generosity has bequeathed much to deserving institutions and they will be long remembered as benefactors, but to many of us their memory lives on as the companions of other days whose wit and spirit for a brief moment made life seem more colorful and more civilized.”

Millionaire’s Playground

Victor and Marjorie Morawetz were among a fortunate group of wealthy Northerners who discovered the South Carolina Lowcountry in the 1920s and 1930s as a perfect place for winter homes and/or hunting retreats. Like the Morawetzes’ restoration of Fenwick Hall, the monies brought by members of this “second Northern invasion” saved many of the area’s historic properties, which were then in imminent danger of destruction by neglect. Many still flourish from the generosity of their benefactors, and some are open to the public.

The home of Revolutionary War statesman Henry Laurens, Mepkin Plantation on the Cooper River was purchased by magazine publisher Henry Luce and his wife, Clare Boothe Luce, in 1936 as a winter hunting retreat. In 1949, the plantation was donated to the Trappist Order of Cistercians Monks. Today, we know this beautiful property as Mepkin Abbey. While it is an active monastery, portions of the property, including the extensive botanical gardens created by Clare, are open to the public. mepkinabbey.org

Hobcaw Barony on Winyah Bay near Georgetown was likewise the winter retreat of investor and philanthropist Bernard Baruch and later, his daughter, Belle. Today, the 16,000-acre property is under the auspices of the Belle W. Baruch Foundation and the North Inlet-Winyah Bay National Estuarine Research Preserve and open regularly for nature tours and other programs. hobcawbarony.org

The remote barrier island, Bulls Island, once a hunting preserve of New York banker and broker Gayer Dominick in the 1930s, is now part of the 62,000-acre pristine wilderness known as the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge. Under the auspices of the US Fish and Wildlife Department, the island is only accessible by boat for day use. Coastal Expeditions’ Bulls Island Ferry makes regular runs from its Awendaw dock. fws.gov & bullsislandferry.com

Image credits: Melinda Smith Monk; courtesy of John Hauser; Fenwickhall.com; courtesy of Library of Congress; courtesy of (Victor) Wikipedia; Brett Tighe; oldlongisland.com; Park Dougherty, Society for the Preservation of Spirituals; (garden) The Charleston Museum; (fenwick disrepair) John Pernell; (fenwick 1933 exterior & interior) Library of Congress; Photographs by (pinkcney) Alfred Eisenstaedt; Getty images; courtesy of (matchabelli) Wikipedia; (manigault house) Library of Congress; (berle) Zuma Press Inc./Alamy stock photo; (grandjany) youtube; courtesy of (cactus garden) The Cactician; (walled garden) Library of Congress; courtesy of (house) Grange Simons; (campers) St. Christopher Camp & Conference Center; images courtesy of (Moses and the Serpent & miniature) Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association; (roper Hospital) the hospital; images courtesy of (The Wreck of the Rose in Bloom & Henriette Charlotte Chastaigner (Mrs. Nathaniel Broughton) Gibbes Museum of Art/Carolina Art Association; (Ft. Sumter Hotel) George Johnson & courtesy of (Liner) wikipedia; (Maybank, house, & Poster) Library of Congress; couretsy of Belle W. Baruch Foundation & The Charleston Museum