Taylor’s latest tome is filled with spicy autobiographical morsels and culinary creations from around the world

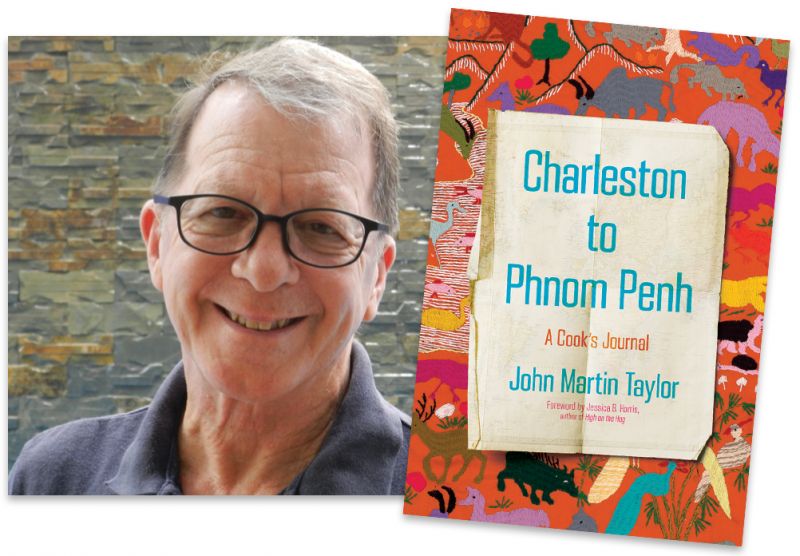

(Left) John Martin Taylor; (right) In A Cook’s Journal,Taylor dishes up autobiographical morsels and spicy tidbits (references to old lovers and his friends The B-52s), with a salty aside or two.

There are many reasons for our city’s popularity, the local cuisine and food scene among them. But it wasn’t always this way.

In 1992, when John Martin Taylor’s Hoppin’ John’s Lowcountry Cooking (Bantam) was published, a revolution of sorts began. The book confronted the status quo and hit the reset button on preconceptions and received ideas. As the one who, if nothing else, put local shrimp and stone-ground grits back on our tables, Taylor revived an approach to food and cookery through his recovery of 18th- and 19th-century Lowcountry traditions and West African roots.

Fast-forward to today: our chefs are celebrities, reviewed and interviewed; heirloom foods abound; sustainability is encouraged; and we expect local and fresh on our menus. Based on what Taylor helped ignite here in the Lowcountry, food is now not only a folkway but a philosophy. In his latest book, Charleston to Phnom Penh: A Cook’s Journal (USC Press, November 2022), John Martin Taylor, aka “Hoppin’ John,” offers insight into how this came to be in his own life and in the Holy City.

Always practical, the author suggests readers shop first for the best ingredients before deciding on a recipe, and he follows his own advice, carefully picking over more than 30 years of his published pieces to put together this satisfying anthology. In it, Taylor dishes up autobiographical morsels and spicy tidbits (references to old lovers and his friends The B-52s), with a salty aside or two. (“No fat, no flavor, no wonder Yankees hated it,” he writes about tasteless mass-produced grits.) Those who may recall Hoppin’ John’s, his legendary culinary bookstore on Pinckney Street, will agree with what food historian Jessica Harris says of him in her introduction: “You’re going to meet a friend.” (Full disclosure: Taylor names me in his afterward as one who helped his initial research into Lowcountry history.)

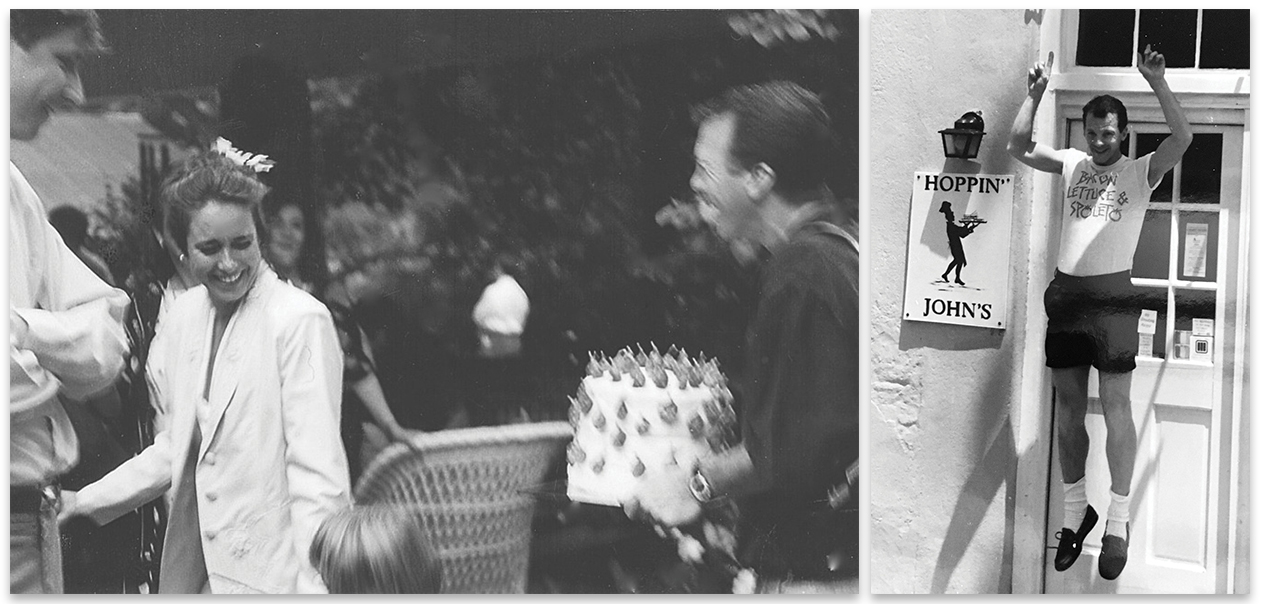

(Left) In the chapter “Why I Don’t Make Wedding Cakes,” Taylor recounts the story of making this confection, studded with candied figs, for his dear friend and local artist Mary Edna Fraser’s August outdoor reception on James Island.; (right) An exuberant Taylor in the late 1980s outside Hoppin’ John’s, his cookbook and culinary shop on Pinckney Street.

Raised in Orangeburg, South Carolina, by adventurous, intellectual parents who owned a wine refrigerator (in the 1950s!), he traveled the country with them, dining in the era’s best restaurants. Yet he never felt alienated by the South and took to its marshes and streams, living on Hilton Head “before the bridge” and learning from extended family far inland, too.

From the first essay dismissing the myths of Huguenot torte (it’s not local, Huguenot, or a torte) to his elegiac, yet hopeful, final essay on loved ones lost, you’ll find yourself in the hands of a gifted cook and raconteur. Taylor mixes stories and recipes (some freestanding, some embedded in tales), while also tracing etymologies of words along with bits of cultural and culinary anthropology gleaned from the many places that he and his husband, Peace Corps country director Mikel Herrington, have lived, including Paris, Washington, DC, and New York, as well as Liguria, Bulgaria, Thailand, and Cambodia.

Whether it’s boiled peanuts or edamame, water chestnuts or watermelons, pesto or sweet potato pie, whatever fascinates Taylor will inevitably fascinate the reader thanks to his seductive, yet straightforward, expository style. At the end (spoiler alert), he names the chief ingredient that has made his life possible, skipping from accomplishment to accomplishment and continent to continent. It’s pure unadulterated joy, he confesses, and you’ll find full measures of it in this eclectic, eccentric, and entertaining new anthology.